A sneak peek into dreams Museveni, Magufuli shared

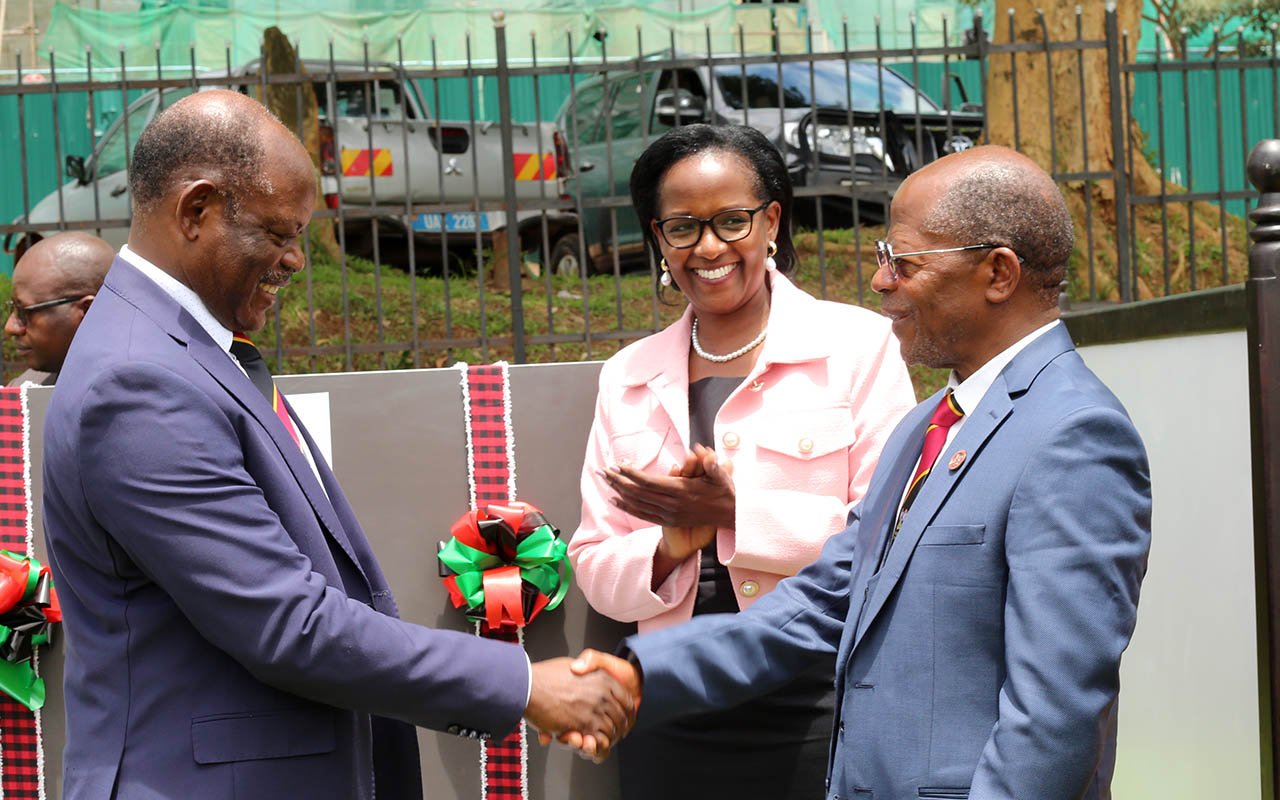

President Museveni (left)and his Tanzania counterpart John Pombe Magufuli (RIP) sign a pact for the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) project in Tanzania in September last year. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- When Magufulu came to Uganda in 2016 to attend the swearing-in ceremony for President Museveni, the ‘bulldozer’used the opportunity to discuss the oil pipeline, something that would later bring the two heads of state together.

When he took to the Presidency in 2015, John Pombe Magufuli, a chemistry teacher, adopted a populist stance to leadership.

In his first months in office, he abolished foreign trips, reigned in on absenteeism, flogged the corrupt and banned excessive expenditure. The acts, brave as they seemed, bought him a nickname- the bulldozer and an immediate international appeal under the phrase; “What Would Magufuli Do?”

They prepared the internal Tanzanian system for a strong-hand foreign policy that would require rigorous work, long hours and strenuous diplomacy. And nowhere would that Foreign policy be seen best than in Uganda.

In 2015, Uganda was at crossroads with implementing a defined and ambitious development agenda. On the one hand, the President favoured the construction of a Standard Gauge Railway to reduce the cost of travel of goods across the region but on the other hand he also struggled with building an oil pipeline to transport Uganda’s oil.

In the small drafts of the oil money, Mr Museveni was also toying with the idea of a local refinery.

These projects required money, which Uganda didn’t have much of, neat bureaucracy across the region which seemed unlikely to come and more importantly a champion.

Magufuli sat in this role – almost perfectly.

In 2016, the ‘bulldozer’ came to Uganda to attend the swearing-in. On his agenda, Magufuli knew to ask for quickening of matters on the oil pipeline. Uganda had been locked in a war of taxes with oil giant Tullow. The British company had been ready to sell its stake to Total, who, if the deal went through, would find a pipeline commercially viable for investment. What with their already known dominance of Tanzania’s oil sector.

Magufuli reasoned with Museveni then – and he would later disclose at a presser in Masaka District on a state visit – that Uganda could get a safer and shorter route to the coast through the Port of Tanga and the Magufuli would individually see to it.

The former infrastructure minister turned-president set about proving his hand by sending ministers to Uganda for long consultative meetings and planning.

In three months from that inauguration, Uganda abandoned the Kenyan route through Lamu and concentrated on the Port of Tanga.

To prove commitment, Mr Museveni withdrew one of his finest ambassadors Richard Kabonero from Rwanda and sent him down to Tanzania.

The moves worked wonders. Uganda’s imports from Tanzania grew from a mere $52m (about Shs190.7b) to $258m (about Shs946.3b). The Uganda airlines project which had come online in Museveni’s fifth term secured an almost immediate landing spot in Dar-es-Salaam.

The two countries, toyed with and eventually held a separate Uganda-Tanzania business forum at which both Presidents attended. It was so important that Museveni, who was flying from South Africa made a stop in Dar-es-Salaam before coming back to Uganda.

At the forum, Magufuli launched his second charm offensive, this time, going for the heart of inefficiency in trade relations. Magufuli complained to President Museveni that revenue officials were frustrating Tanzanian businessmen.

He complained that Tanzania businesses were still struggling to put their goods on Ugandan shelves. Ugandan business in turn complained of the prevailing ban Tanzania had placed on Ugandan sugar and the trade barriers that had come up on eggs, chicken and cows.

Both Presidents listened, attentively.

Magufuli, joking in his speech, told Mr Museveni to lend him Uganda for a few days so that he could govern it.

Museveni would return the camaraderie at a joint press conference in Masaka where he told the press “Even me, I am thinking of using his [Magufuli] methods to fight corruption and you will see soon”.

In Magufuli, Mr Museveni saw a re-incarnation of the pragmatism and buoyance of former Tanganyika/ Tanzanian President Julius Kambarage Nyerere (1961-1985), his political idol and in Museveni, Magufuli saw a reliable partner and pan-African.

The two would rekindle their warm relations when, in the thick of the Pandemic and with Tanzania openly denying its existence, Mr Museveni flew to Tanzania to sign the paperwork for the East African Crude Oil Pipeline.

“Museveni asked me if he could come but wear his mask and I told him, even blankets he can bring,” Magufuli told a cheering crowd in Kiswahili.

Magufuli, in his short presidency had gotten Mr Museveni to shelve, for a short while, the SGR, concentrate on an oil pipeline, sign host government agreements for oil companies, allow for the sale of Tullow assets, open a new border post, and deploy his finest Foreign Affairs man on regional affairs.

In return, Magufuli opened Tanzania for Ugandan goods, lifted a draconian ban on Ugandan sugar, accepted for a new border operation and signed and committed to building the world’s longest heated crude oil pipeline.

It was little wonder that in writing his eulogy, Mr Museveni described Magufuli as a pragmatic leader who worked for the good of all East Africans.

For Magufuli, whose legacy will remain in debate for years, Uganda will be in debt.