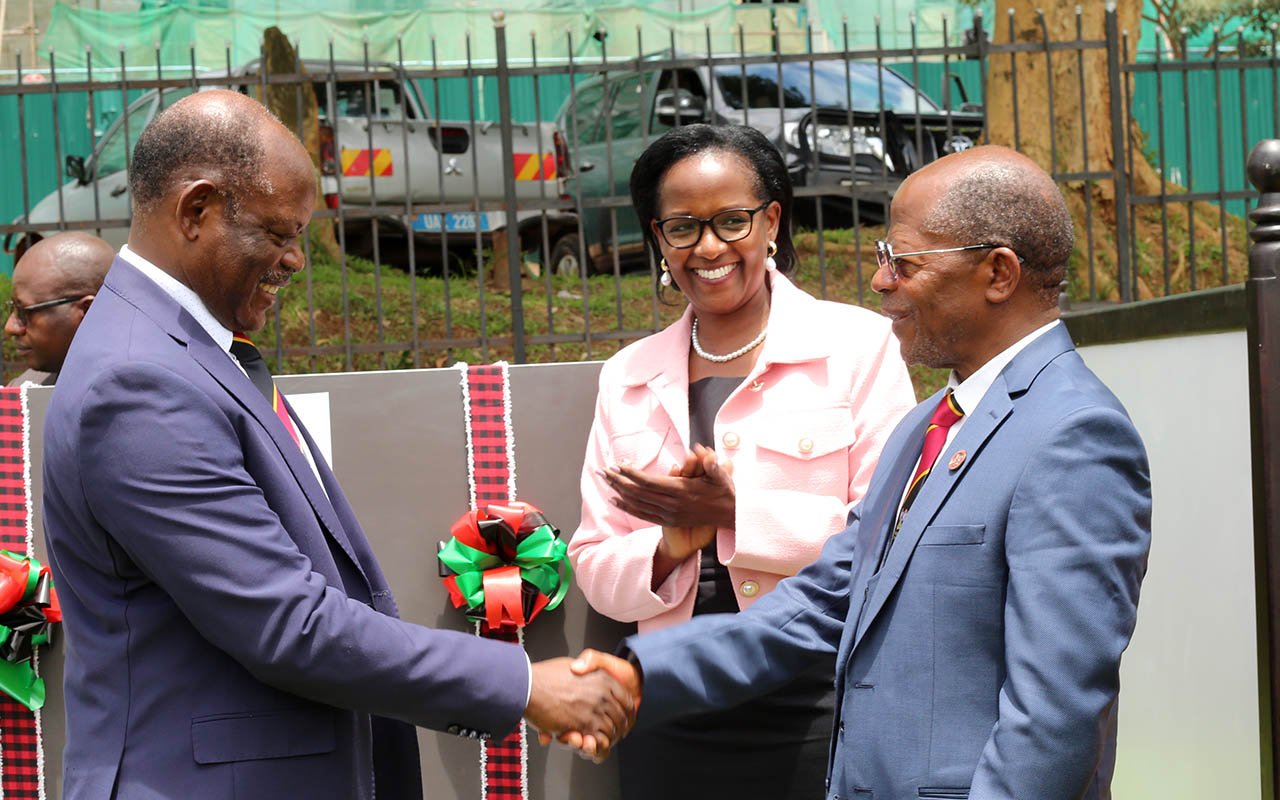

Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) deputy Executive Director, Mr David Luyimbazi, during an interview at the KCCA offices in Kampala on November 12. PHOTO/DAVID LUBOWA

|National

Prime

We’re on course to transform Kampala, says Eng Luyimbazi

What you need to know:

- Eng David Luyimbazi is the deputy executive director of Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA).

- In an interview, he explains to Daily Monitor’s Amos Ngwomoya City Hall’s plans to fix problems of garbage, traffic, bad air quality and illegal developments in order to transform Kampala into a beautiful, organised and livable city.

What is your strategy for the city and what have you achieved in the last one year so far?

We launched Kampala Capital City Authority’s five-year strategic plan for the period 2020/21- 2024/25 on September 29, 2020. This strategic plan is aligned to the National Development Plan III and [it] is the principal tool that guides city-wide interventions.

It calls for an investment outlay of Shs7 trillion over its term and moots new developments for the capital city which Ugandans can be proud of such as roads, junctions, signalising [road intersections], social protection, neighbourhood planning, street, urban farming, urban regeneration, and slum conversion, among others.

The strategic plan is underpinned by sectoral strategic plans such as the Kampala Physical Development Plan, Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area Multi-Model Urban Transport Masterplan, Kampala Sanitation Improvement and Financing Strategy, Kampala Public Health Strategic Plan and the Kampala Smart City Strategic plan, among others.

And the achievements?

We have [registered] modest achievements in light of the unprecedented conditions of Covid-19 that we are operating under. Covid-19 has contracted the country’s resource envelope, which means that adjustments have had to be made towards this reality.

Our focus has been to effectively conclude major ongoing committed programmes such as the $175m (Shs625b) World Bank-financed 31-kilometre Kampala Institutional and Infrastructure Development Programme II (KIIDP-2).

We have also commenced major programmes such as the $288m African Development Bank-financed 69-kilometre Kampala City Roads Rehabilitation Project (KCCRP); the Shs89b Japanese International Cooperation 30-Junctions Improvement and Traffic Control Centre projects, Euros77m French Development Agency-financed 20,000 Street Lighting Project, $450m World Bank-financed Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area project; Euros250m United Kingdom Export-finance 300-kilometre Road Rehabilitation project, and implementation of a public-private partnership (PPP) with METU Zongtong for 1,000 city buses.

What are Kampala City’s major challenges and how do you intend to address them?

The major problems in the city are roads, drainage and solid waste management. In respect to roads, we have about 600 kilometres paved roads and about 1,500 kilometres of unpaved roads. However, for the unpaved roads, at least 60 percent of them have outlived their usefulness and they need to be paved [afresh] and the gravel roads carry so much traffic that they need to be upgraded.

So, we need money to invest in rehabilitating roads and upgrading others. Despite the problems that we are focusing on, we shall only solve like may be 40 percent of the problem of roads.

When it comes to drainages, we have a Drainage Master Plan that requires about $200m and we have so far been able to raise at least $50m through the World Bank that we are using towards the Nakamiro and Lubigi channels. So, about three quarters of storm water drains remain unfunded.

Now when it comes to solid waste management, with only 12 functional garbage trucks in the city owned by KCCA combined with the help we get from our concessionaires like Nabugabo and Homeklin [waste management companies], we are only able to collect 50 percent of the waste we generate daily, yet we generate about 2,500 tonnes of waste daily and the rest finds itself in our drainages.

So, the need remains big. We need an investment in solid waste where we can recycle solid waste or reduce the amount of waste and this is where the need for more funds comes in.

The President had approved that we use a pre-financing modality and we are trying to weigh in this Covid-19 era whether it’s something that we can begin to implement.

So, we are engaging the Ministry of Finance to see how the strategy of pre-financing works. Under that strategy we will invite investors to come and invest and they get paid later. It’s a service credit arrangement and we believe this strategy can give at least 70 percent solution to Kampala’s problems.

Overall, we need a budget of at least Shs1.4 trillion every year from government and if we complement this with funding from development partners, then the city can have a new look.

The KCCA Act provides for the Metropolitan Physical Planning Authority (MPPA) where development in the city has to be aligned to the Metropolitan areas of Mukono, Wakiso and Mpigi. But there is no indication of coordinated planning between these satellite areas.

It’s true that the MPPA (Metropolitan Physical Planning Authority) hasn’t been established, but it doesn’t mean that there is no coordinated effort. Under the Ministry of Kampala and the Metropolitan Affairs, this is where these efforts are being coordinated and not at City Hall. To show that that coordination is taking root, the next lending by the World Bank is looking at the Greater Kampala, and not Kampala City alone, because the drainages in Kampala are connected to those in Wakiso and other financiers are making it clear that the lending for Kampala can only be done when it’s syndicated regionally.

Cases of collapsing buildings are on the rise in the city. Our investigations show that KCCA has failed to play its watchdog role against illegal developments

This is again the situation where the public blames us for the failure of people to comply with applicable laws. Of course, you can blame us because by the time a developer constructs three floors you cannot have failed to detect them.

For the Kisenyi incident, we did issue notices to a developer, but he defied them. Everyone is duty-bound to comply with the law. However, executing closure of a site is a process and takes time and this particular developer took advantage of the lockdown because our workforce had been reduced.

We have decided to set up a multi-sectoral task force which involves KCCA, National Building Review Board, Police, and the Occupation and Health Unit of Ministry of Gender. We have identified about 3,000 structures in the city that are illegal and we are going to begin an operation to ensure that developers regularise their constructions or else we demolish them.

There is a housing crisis in the city amid a swelling population. There are fears that this could worsen the planning challenge.

Our strategy going forward, and we are working with the United Nations Development Programme, is to have slum conversion. Convert slums into low-cost, high-rise buildings so that you can be able to accommodate people who live in slums and release a balance of the land for major development.

Of course, it will require collaboration with landlords who own land. For example, if you have a 100-acre piece of land and we develop the seven acres, you release the 93 acres for other developments so that the landlord can get a share on the return on investment, KCCA gets revenue, slum dwellers get decent accommodation and the investor gets a profit. We intend to have the first pilot of this project in the next two years.

KCCA recently signed an MoU with METU Company to bring buses to the city. However, you did this without first addressing the problems which frustrated the Pioneer Buses, and the general transport problem in the city.

This is a public-private partnership (PPP). Pioneer Bus also came through a PPP framework and they were unable to manage the risks that were bound to them and they were going to be competing with matatus (taxis) and boda bodas. I really don’t have a clear picture of what happened to them. METU is coming on the scene with the full knowledge of the challenges which Pioneer Bus faced.

The investment and operating risks are going to be on METU and they are fully aware of the risks they face. Our job is to provide them with a tenure of operation where they have exclusivity so that they can be able to put enough buses on the road with the quality of services that will attract passengers and in turn be able to make a profit.

The former executive director, Ms Jennifer Musisi, cited political interference as one of the reasons for her resignation. How do you plan to achieve your development agenda in a city that is majorly dominated by Opposition politicians?

The issues I talked about like poor roads, drainages, garbage and traffic jam don’t distinguish between political parties. Our core focus should be how we do business and that shouldn’t create differences between the technical and political wing.

We need to focus on problems that affect citizens of Kampala and I think any politician would want to solve that because that’s what gives them mileage. Therefore, our focus is on the problems and whatever we do should be geared towards serving the public.