Prime

Queen Elizabeth is dead, good riddance

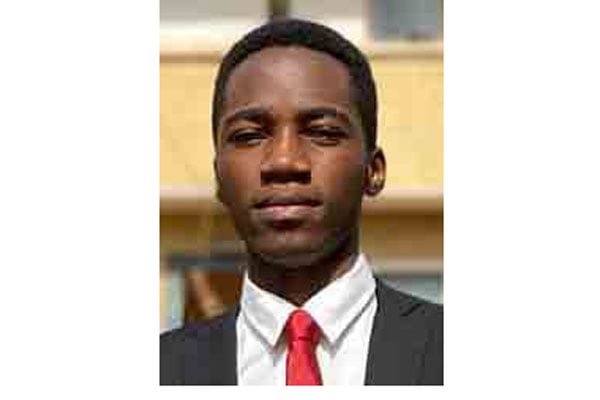

Author: Nnanda Kizito Sseruwagi

What you need to know:

- Nnanda Kizito Sseruwagi, a Law student, argues that we cannot reduce Elizabeth to a mere remnant of colonial times. He says the queen was the top most supervisor of a colonial government that massacred and displaced thousands of people.

Nnanda Kizito Sseruwagi, a Law student, argues that we cannot reduce Elizabeth to a mere remnant of colonial times. He says the queen was the top most supervisor of a colonial government that massacred and displaced thousands of people.

Is there a wrong way to mourn? Is there a wrong way to mourn the late Queen Elizabeth specifically? These are some of the questions that crossed my mind in the wake of heated debates on social media following the reportedly “painless” death of Elizabeth.

How unfortunate!, if that was so. Death is a long time coming and the only hand of justice for some classes of people, so it would be quite misused if it occurred “painlessly.” What was special about Elizabeth? A privileged, lucky birth? Did she ever qualify herself as anybody who stood in a bigger picture other than her birthright? I don’t think so. I struggle to scrap up fragments of worthwhile causes she exhausted herself about, at least emotionally, as Princess Diana did.

Some of Elizabeth’s painstaking contributions to a better world was granting royal pardons. One of such pardons was posthumously granted to Alan Turing in 2013. It must have been such a laborious task for the Queen to find mercy in her heart and forgive a computer scientist and mathematician who had been convicted for homosexuality in 1952. It took Elizabeth 50 years to summon the courage and mercy to pardon a man who helped Britain win the Second World War by cracking the “unbreakable” Nazi Germany Enigma code.

If the humane and appropriate thing to do now is to mourn Elizabeth in kind language, the humane and appropriate thing to do in 2013, if not earlier, would have been for Elizabeth to posthumously seek the pardon of Turing, whose unfair conviction led to his suicide following chemical castration.

If Elizabeth couldn’t find remorseful language to seek Turing’s pardon, I cannot find kind language to mourn her demise. But why should I, as an African, be so angry at Elizabeth that her death should be my bliss? Why? Yet many other Africans especially our political leaders, those in power and Opposition alike, celebrated her life and mourned her death in eulogies that magnified her beyond her imperial stature by projecting her as a grandmother? You could feel it while reading their eulogies to her that the only blame they might place on her memory is denying them of genuine connection, familial love and emotional neglect. You could get the sense that most of them were simply rebranding colonialism as a long-standing relationship with Britain.

But I belong to the other side of mourning. I belong to the Uju Anya school of mourning, which rejects the policing of Africans’ emotions about how they feel about Elizabeth’s death. Elizabeth was the paragon of the British Monarchy. She was the archetype of British colonialism and imperialism. I cannot find a more deserving image to hate. I am as much a Muthoni Mathenge, who suffered torture at the hands of the British in Kenya as Elizabeth is the pinnacle of British Imperialism. We cannot reduce Elizabeth to a mere remnant of colonial times. She was an active participant in colonialism who went far and beyond to stop independence movements in different parts of the colonized world and tried to keep newly-independent colonies from leaving the commonwealth. She was the top most supervisor of a government that massacred and displaced thousands of people who look like me in many parts of the world. But even if she had done nothing and sat idly throughout her life, she would still have been a passive beneficiary of the colonial inheritance whose evils she never once cared to apologise for.

Some British historians and apologists of imperialism have praised the English Monarchy for banning slavery long before the American Civil war through laws passed in 1807 and 1833. This is a lucid editing of history which footnotes the struggles of the enslaved while falsely capitalising the absent morality of the British Empire. Not only did they explicitly exempt their profitable colonies from the 1833 slavery ban, they also went far and beyond to remove any suspicions of doubt we would have had that they regretted slavery by undertaking one of the largest loans in history to compensate slave owners for losing their property, aka slaves, aka people like you and me, through the 1835 slavery ban.

If slavery was so bad, and the British government as patronised by Queen Elizabeth regretted it, why did it have to spend five percent of its Gross National Product to compensate slave owners up until 2015? The backbone of British imperialism was slavery. And when the United Kingdom officially banned slavery, it compensated slave owners, not the victims. So how am I supposed to feel about the death of the symbol of such a system of cold tyranny? Indeed the former Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Eric Williams, was right to remark that “British historians write almost as if Britain had introduced Negro slavery solely for the satisfaction of abolishing it”.

Strings attached

The wealth and development of Britain, which saw its pound gain the power that it has today were directly built out of the impoverishment and underdevelopment of its colonies. My current struggles with access to basic needs of life due to the political and economic challenges of my country are directly linked to the equation of the development of Britain which guaranteed its citizens the relative comfort they enjoy today. All British colonies were primarily governed not for their civilization as the colonialists arrogantly posited, but for the benefit of Britain. Our deprivation was the credit that financed Britain’s development. The industrialisation of Britain was premised upon the enslavement and underdevelopment of Africans.

Colonial administrators were some of the most highly paid civil servants, literally paid for through the excruciating labour of the colonised. Not only were we colonised, we also paid for it. Whereas some might be tempted to argue that there were some benefits from colonialism such as the construction of railways, roads, and dams, this argument is utterly oblivious of the fact that these were essentially projects designed to serve the colonial enterprise. If not so, why would blood have had to be spilled to inherit them during the decolonisation struggle? Railways and roads weren’t built to link supply and demand within the colonies, rather they were built to link colonies to the coast in order to facilitate the export of minerals other products stolen from the colonies. Many countries have in fact built magnificent infrastructures that rival anything British Imperialism established without having had to be colonised in the first place.

Queen Elizabeth did not have to take it all upon herself to dismantle this age-old system of oppression that she inherited from her father. All she ever had to do was to live up to the principle of reparations. To show remorse for the evils perpetrated for centuries by the British monarchy. But she lived a life akin to the denial of all these wrongs. You cannot be an heiress to an empire that demolished the ways of life and social traditions of almost the entire global south, and go through your 70-year reign with a clean conscience as if nothing happened. Many of the problems we face in these colonised countries today, problems which our generation such as past generations will bequeath to the next generation, were directly a result of the colonial experience. Elizabeth had sufficient time to pay this moral debt that the English monarchy ought to have paid years ago, but she didn’t try to pay it. And it wouldn’t have costed much to try.

The principle in this is not to undo the evil atrocities of colonialism because we cannot even evaluate and quantify them in the first place. The principle is simply to atone for them. To accept that a wrong was done, and stand up to say sorry to those who were wronged. Elizabeth didn’t find the strength in 96 years to do this.

There is so little I can do to fight back against the British empire for the crimes it committed and continues to commit through the legacy of colonialism. But at least I can celebrate the death of their beloved Queen. There was never a right time to colonise us. There can never be a right time to be uncivil by celebrating death. But Elizabeth’s death gave us a chance of the “right time”.

Good riddance, Liz.

Authored by Nnanda Kizito Sseruwagi, a fourth-year law student at Makerere University.