Prime

The messy affairs of Uganda’s generational politics

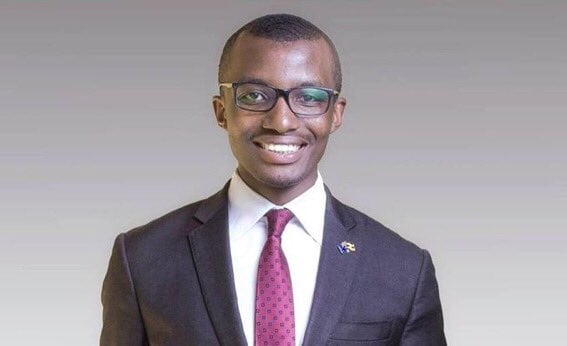

Raymond Mujuni

What you need to know:

It will take Omoro District nine years to spend the amount of money spent in a day of burying their leader Jacob Oulanyah.

As a single event, the death, public mourning and burial of the former Speaker of Uganda’s Parliament, Jacob Oulanyah, provided a rare insight into the capacity of administration our current crop of leaders are capable of.

From handling of the news, to the eventual debate on the cause of death, Oulanyah’s funeral brought together a cast of Uganda’s ‘revolution generation’ which ascended the reins of administration – not power – of Uganda’s public affairs after the 1986 guerilla war.

Minister in Charge of the Presidency, Milly Babalanda, for example, on whose shoulders the leadership of government’s state funeral fell, is four years shy of Jacob Oulanyah. She was sitting her primary seven exams when the National Resistance Army (NRA) was negotiating its final assault in 1985 and years later, she joined in the fray of politics as a mobiliser for both Kamuli Woman MP Rebecca Kadaga and Kirunda Kivejinja (RIP), the maverick ideologue and former deputy prime minister.

Norbert Mao who emerged as a coalescing figure in the funeral is three years older than Milly, and just a year shy of Jacob Oulanyah. He is fixed in the annuls of history as the pinnacle of student politics. For his campaign and reign of Makerere, the nostalgia of resisting structural adjustment programmes set in motion by the generation before them, remains a touch point of history.

What though, of these individuals – and leaders of their generation – explains the calamity of disorganization that was at the funeral? What could have been done better? And why wasn’t it done better? Who is responsible for what part of the mess? And how can we collectively learn from it?

These questions plagued my mind. I was watching the funeral proceedings from a farm deep in Kalagi where hunter-gatherers are still part of the economy – just 38 kilometres from the mighty Kampala city are people who haven’t ‘evolved’ from the first means of production – but I digress!

Let’s start with setting the scene for where the burial happened. Omoro District, the homeland of Oulanyah, sits in the northern Uganda belt of the country where despite increased population trends, government services have remained fixed. Four in 10 people in northern Uganda live in poverty, only rivaled by eastern Uganda. If you adjust the data to add those hanging on the thread and likely to slip back into poverty, the number moves to 7 in 10. The current generation of children in school in northern Uganda are the first crop to truly experience free and robust government education after a 20-year civil war dragged the progress of the region.

To spend Shs1.2 billion burying Oulanyah in Omoro meant spending nine times the district annual revenue. I don’t think I explain that well. It will take Omoro District nine years to spend the amount of money spent in a day of burying their leader Jacob Oulanyah.

While the debate on burial expenses was weaponized on ethnic lines, it would truly have taken a true leader to step back and ask, is this the best use of money for Omoro District?

Oulanyah who enjoyed a burial cover from Parliament and could marshal enough friends to cater any expenses would have questioned this – and I know this because in his last known public interview which was with this dear columnist, he was riled by government expenditure in comparison to the social service problems that were being neglected.

But this isn’t an expenditure problem. It is, by all measure, a leadership problem and by a large extent a generational problem. Had Mao succeeded in stopping the Structural Adjustment Programmes, it is very likely that the funeral company burying Oulanyah would have been the UPDF – or the Police funeral services. It is also likely, had he succeeded that decentralization wouldn’t have taken the shape it did and Omoro would still be a part of the Gulu district.

But ifs, ands or maybes don’t answer the question at the heart of the leadership problem. Perhaps, the better question, to which I will leave you dear reader to draw your own answers is; what metric in that generation picked Babalanda as a key decision maker over Norbert Mao?

Why are our competent chefs seemingly on the outside of the kitchen while the plumbers dabble in deciding what seasoning will keep the dinner table full?