Prime

Ugandans can also do what Sri Lankans did

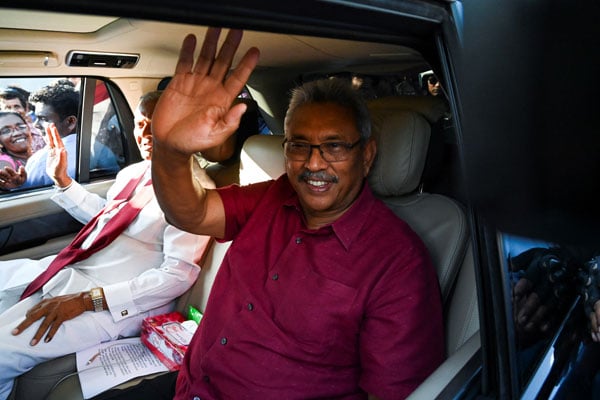

Author: Okodan Akwap. PHOTO/FILE.

What you need to know:

In Uganda, the government would have collapsed a long time ago if it even tried to fight corruption in public offices

Governance

Sunday Monitor columnist Musaazi Namiti seems as eager for change in Uganda as many Ugandans are. But in his column of July 17 titled, ‘We should hire Sri Lankans as consultants for change in Uganda,’ We should hire Sri Lankans as consultants for change in Uganda he sounded at once optimistic and pessimistic.

“The Sri Lankans appear to have succeeded where we have struggled to make progress, and maybe it is about time we hired them as consultants. They should advise us on how to organise peaceful protests to secure change,” Namiti wrote.

I don’t share his pessimism. No doubt, Sri Lankans have accomplished what many Ugandans have longed to achieve for too long. But we don’t need them to serve as consultants to “advise us on how to organise peaceful protests to secure change.”

I think that the key difference between Uganda and Sri Lanka is that the conditions for peaceful protests leading to change were ripe. Here, such viable conditions are yet to ripen. Still, Uganda is headed for a social revolution. The conditions are ripening. I hear the clock ticking. Tick tock.

Do I hear someone say that Uganda now has no viable revolutionary movement? Maybe. But in his book, Revolutions and Revolutionary Movements, James DeFronzo, a well-known American sociologist, cites factors that can influence the development of a revolutionary movement even in a country of docile people such as Uganda. Let us look at some of these factors.

First, the extent of inequality and impoverishment within a society’s population. In Uganda today inequality is everywhere. It is firmly institutionalised in the distribution of opportunities in education, health, public service, etc. Indeed, our society has an ever widening gap between the rich and the poor.

Second, the degree to which the population is divided along ethnic lines. Tribalism is alive and kicking in Uganda. Nevertheless, when a startup opposition political party sweeps votes in Buganda, it is described as sectarianism. But when NRM garners 100 percent votes in western Uganda, it is seen as patriotism. When people from one ethnic group dominate appointments and power in the Cabinet, the army, public service and top-drawer public agencies, they are “qualified.”

Third, the perception of corruption of governmental officials. In Uganda, the government would have collapsed a long time ago if it even tried to fight corruption in public offices. The vice has killed many public institutions. It has killed the decentralisation process that was spawned by one of the finest policies Uganda has ever produced – the Decentralisation Policy 1992. The policy was neatly operationalised by the Local Government Act 1997, which also withered years ago.

Fourth, the level of armament and degree of loyalty of a government’s military forces. One man in this country allegedly sees the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) as a personal army. What more do you need to understand where UPDF’s loyalty is supposed to lie?

Fifth, the cultural tradition of violence as a means of protesting perceived social injustice. The preamble to the Constitution is a cry to avoid the kind of violence that accompanied changes of guard in Uganda. Ignoring that cry is a fatal mistake. I was 12 when Milton Obote was deposed in 1971. I was 21 when Idi Amin was deposed in 1979. And I was 27 when Obote was toppled again in 1985. Needless to say, I have seen enough violence.

Unfortunately, I could be wrong. On top of the above factors, DeFronzo’s book singles out mass frustration as a trigger of local uprisings. Look at what is happening in Uganda today. What do you see? Mass anger. Mass frustration. Mass hopelessness. Mass malnutrition. Mass poverty. Mass unemployment. These things may one day erupt into a Sri Lanka-like mass protest. Why?

“A large proportion of a society’s population becomes extremely discontented; which leads to mass-participation protests and rebellions against state authority. In technologically limited agricultural societies; the occurrence of rural (peasant) rebellion or at least rural support for revolution has often been essential,” DeFronzo wrote. Tick tock. Tick tock.

Mr Akwap (PhD) is an associate consultant at Uganda Management Institute