We can’t afford mortgage but let’s regulate rent

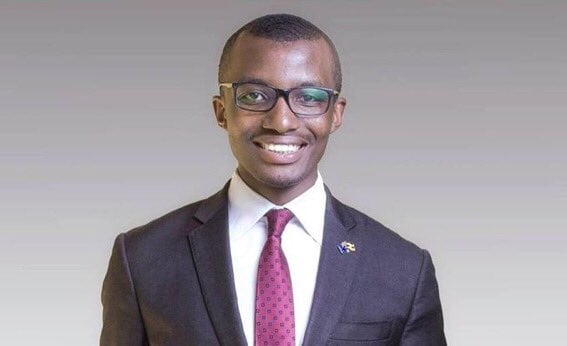

Raymond Mujuni

What you need to know:

That morning when the landlord knocked at my door, I learnt through my frustration, of the rent restriction act and the boards that government should have at each municipality and town council to regulate housing rents and relationships between landlords and tenants

In the early days of leaving my father’s home, I received a knock on the door in the wee hours of the morning. My new landlord was outside holding what looked like a brown envelope.

I, of course, hurriedly opened and offered to boil him a cup of tea which he seemed less enthusiastic about. In the envelope, he’d carried a new tenancy agreement that was about to fundamentally alter my relationship with him – and at large my relationship with housing.

He was increasing the rent by 120 percent - effective the following month. He still had, in my debt, two months’ worth of rent and a litany of complaints about failing water heating, broken cisterns and a paint job that he’d promised when I got into the house but never done.

I left the house at the end of that month – and with that forfeited my two months of hard-earned money.

However, there were many laws that had been broken in the process, of that I am sure, but for some reason I felt completely helpless to take on a landlord. The Ugandan political establishment – in whose ambit it rests to appoint rent restriction boards had largely left this space unattended. It isn’t enough that there is a housing deficit in the country – north of 1.2 million housing units, but it is also that existing tenant-landlord relationships are unregulated and tilt power dramatically and corruptly into the hands of landlords.

But the purpose of this column today isn’t to resolve that; it is to see the trees for the forest.

Uganda has pursued a rather interesting development paradigm. Over 60 percent of the country’s GDP is made in the city. A friend at URA whispered that the breakdown is even strange because a lot more of that percentage is made on just two streets of Kampala. What centralizing development means is that it attracts populations to the centre of the success story. The Kampala dream, call it that if you may, has seen the population of the city explode through the years. From 330,000 people at independence to 1.5 million residents and close to 4 million workers.

At least 4 percent of the national population lives in Kampala and 11 percent work in the city.

This has caused a considerable demand on housing – low cost accommodation and a need to regulate the housing market.

The first way is to temper the mortgage market. Interest rates of over 15% put the mortgage market well out of reach for many Ugandans but government cannot succeed in this endeavor because a lot of the money in circulation isn’t infact Ugandan money. It is multinational capital washed through tax havens and enriching less than 1% who see their future and that of their children outside of the country. How that came to be is fodder for rich intellectual debate on capitalism, the free market, its failings and successes.

The second way, and the one in which government can succeed really, is to enforce regulation in the housing market.

That morning when the landlord knocked at my door, I learnt through my frustration, of the rent restriction act and the boards that government should have at each municipality and town council to regulate housing rents and relationships between landlords and tenants.

Government today should wonder why, just 7 years after colonizing Uganda, the British colonial government sought to regulate the housing market. It’s the stuff revolutions and anger are made of. Suffice to say, the 7% of people who work in the city and live out of it are enough a cocktail to mobilize against the status quo.