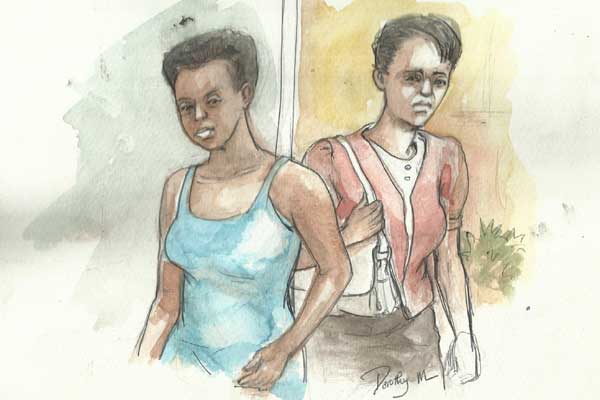

Court upholds Uwera sentence

What you need to know:

- The court that tried and convicted Mrs Jackline Uwera Nsenga of the murder of her husband ruled that she had deliberately and knowingly knocked her husband with a car on January 10, 2013 at their residence in Bugoolobi, Nakawa Division in Kampala.

One of the key ingredients of a murder case that must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt is that of malice aforethought.

The court that tried and convicted Mrs Jackline Uwera Nsenga of the murder of her husband ruled that she had deliberately and knowingly knocked her husband with a car on January 10, 2013 at their residence in Bugoolobi, Nakawa Division in Kampala.

Conviction

There is no doubt that the injuries the deceased sustained were those from which he died. Lawyers acting for Uwera appealed the conviction and one of the key issues that the Court of Appeal had to determine was whether malice aforethought was satisfactorily proved in the trial court.

The trial court relied on circumstantial evidence to conclude that Uwera deliberately knocked down her husband and these circumstances included the dying declarations of her husband, the threat that Uwera is purported to have made to her husband and a lady she suspected her husband was having an extra-marital relationship with, the acrimony of their marriage relationship and Uwera’s conduct before, during and after the commission of the crime and the manner in which the deceased was repeatedly overran with the vehicle.

Admission by the accused

The trial court correctly observed that direct evidence of intent such as an admission by the accused person is very rare, and court must, as a result, attempt to prove intent by inference through circumstantial evidence.

Court also observed that circumstantial evidence is about the cumulative effect of the totality of the evidence and therefore the different pieces of evidence should not be looked at in isolation of each other.

Court noted that in order to justify, on the circumstantial evidence, the inference of guilt, the facts of the case must be incompatible with the innocence of the accused and incapable of any other explanation other than the guilt of the accused.

The cardinal question is whether, in truth, these cardinal principles of law were correctly applied to this case.

Circumstantial evidence

Can’t circumstantial evidence be manipulated to infer guilt of an otherwise innocent person?

In this particular case, the husband in his dying declaration categorically stated that he was knocked by the car and not the gate.

Uwera stated that she knocked the gate which then hit her husband. Independent forensic evidence clearly established that the deceased was hit by the gate and then dragged by the car.

There is no doubt that the acrimonious marital relationship had taken its toll on the deceased. Why then did the court not resolve this cardinal issue in favour of Uwera as it should have?

The Court of Appeal noted that it is not mandatory in law that the dying declaration of the deceased needed corroboration.

To the court the evidence of corroboration merely strengthens the prosecution evidence. Was this, however, a piece of evidence that needed corroboration or was a major contradiction in the case that should have been treated as such?

Prosecution

There were two equally important facts that prosecution did not prove in the trial court; that Uwera deliberately stepped on the accelerator of the car as the gate was being opened and that she knew that her husband had come to open the gate that fateful evening.

On the contrary, evidence on the court record indicated that this was the very first time ever for the deceased to open the gate for his wife.

The Court of Appeal ruled that it was immaterial that Uwera did not know that it was her husband who was opening the gate, as she would still have been found guilty of murder, if it had been the gateman who had been killed instead of her husband. If Uwera did not know who had come to open the gate for her that night, this then renders the circumstantial evidence irrelevant to the case.

A possible and most likely explanation to what happened that evening was that Uwera stepped unintentionally and mistakenly on the accelerator of the vehicle as she engaged the gear from the neutral to the drive mode.

This is not uncommon when a vehicle is left idling in the neutral gear mode. In view of these can it be said there are no other co-existing circumstances which would weaken or destroy the inference of guilt in this case? Can it be said that the circumstantial evidence pointed irresistibly to the intention of malice aforethought?

Are the facts in this case incompatible with the innocence of Uwera and are incapable of explanation upon any other reasonable hypothesis other than the guilt of Uwera? The law is clear on this; the circumstances must be such as to produce moral certainty to the exclusion of every reasonable doubt.

The Court of Appeal concurred with the trial court on the issue of the threat that Uwera issued to her husband and Lorreta on December 19, 2012 and the unfortunate events of January 10, 2013.

To the court, the law on past threats to the deceased can be good evidence to support a conviction.

However, there must be sufficient proximity between the threats and the occurrence of death in order to form a transaction.

Uwera however denied making the alleged threat. The trial court considered the demeanour of Lorreta to believe her and disbelieve Uwera.

To the court Lorreta had no reason to lie as she was also a cousin of the deceased.

Court, however, observed that by the time Lorreta left the home of the Nsengas she was not on good terms with Uwera and as such one could not to expect her to speak the truth or favourably about Uwera. The threat complained of was not however explicitly a death threat as the trial court perceived.