How pandemic made a bad situation worse

Karimojong women recieve Covid-19 relief food items at Kosiroi Sub-county headquarters in Moroto District in April 2021. PHOTO/TOBBIAS JOLLY OWINY

What you need to know:

In the third instalment of our series titled Poverty Made in Uganda, Tobbias Jolly Owiny explores how the coronavirus pandemic and its mismanagement worsened the score of poverty in Uganda.

In March of 2020, damage was unwittingly inflicted when President Museveni started locking down sections of the Ugandan economy to effect coronavirus pandemic curbs.

The country’s informal sector, which comprises small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with low capital, as well as workers with no social safety net, was arguably the most affected. The sector is responsible for 75 percent of Uganda’s jobs and contributes 51 percent of her gross domestic product (GDP) as per the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (Ubos) 2021 report.

In fact, the Finance ministry’s Poverty Status Report 2021—released in February of 2023—comes to the conclusion that the pandemic, including reactions to it, fuelled a general increase in poverty in Uganda.

After registering her index Covid-19 case in March of 2020, disease control measures such as suspension of public transport, closure of schools and bringing in social distancing curbs that handicapped many SMEs took root in Uganda.

The Covid-19 curbs increased operational costs, forcing many businesses to lay off workers. Consumption and savings were also negatively affected as many Ugandans were cooped up indoors.

The Uganda National Household Survey (UNHS) of 2019/2020, for instance, indicates that the mean monthly consumption expenditure (Shs98,677) was higher pre-pandemic.

The UNHS further shows that the figure “decreased to Shs94,859 during the pandemic.” It adds that “the reduction was more pronounced in rural areas (from Shs86,524 to Shs73,413) than in urban areas (Shs146,834 to Shs138,145).” This triggered an increase in the poverty rate from 18.7 percent before the pandemic to 21.91 percent during the pandemic.

There was also a gendered aspect to poverty, with the rate in male-headed households increasing to 21.83 percent compared to 22.1 percent in female-led homes.

“It is likely that males, who are the major breadwinners in many households, lost jobs or closed businesses, consequently, poverty was bound to increase given the loss of livelihoods,” the report hypothesises.

Before the pandemic, poverty rate in rural areas stood at 20.58 percent as per UNHS 2019/2020 data. During the pandemic, it increased to 26.86 percent. Meanwhile, in urban areas, the increment was from 11.2 percent to 11.9 percent.

Urban areas are said to have fared better because of better coping mechanisms, past savings and a flexibility that saw their inhabitants swiftly change either business types or careers. Besides, households in rural settings were significantly bigger.

According to the UNHS data, households with a head aged 31-60 years witnessed an increase in poverty rate from 18.7 percent to 21.9 percent. Elsewhere, those with heads aged 60 and above, saw their poverty rate increase from 17.33 to 20.27 percent.

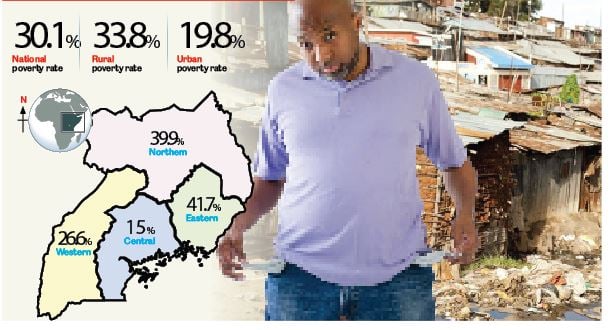

Regional indicator

At the sub-regional level, in 2019/2020, most sub-regions in northern Uganda experienced significant increases in poverty rates. The pandemic was also associated with a statistically significant increase in the poverty rate in Teso, Tooro, and Bukedi sub-regions.

Specifically, Covid-19 and its curbs such as hard lockdowns caused a 4.59 percent increase in the poverty rate in northern Uganda. The impact was significant in Karamoja, Acholi and West Nile Sub-regions. Lango Sub-region was, however, not impacted as its peers.

In 2019/2020, at least 2.8 million households were reported to operate non-crop farming businesses that engaged about 4.9 million people. Sixty percent of the enterprises were in rural areas, with up to 95 percent under sole proprietorship.

The pandemic dealt such businesses a bad hand, with non-crop farming falling from 35 percent to 28 percent. They weren’t alone though. Informal employment in trade, tourism, transport, hotel and hospitality were also significantly affected due to pandemic curbs.

Elsewhere, the poverty rate in households with at least one member employed based on a written contract decreased from 4.2 percent to 3.1 percent. Households with at least one member working based on an oral contract, meanwhile, experienced an increase in poverty from 14.01 percent to 18.53 percent.

In fact, informal workers experienced a significant loss of employment opportunities and a reduction in earnings during the pandemic.

From bad to worse

According to the latest World Bank economic analysis of Uganda, the country’s economy is emerging from the devastating impact of the pandemic, but prospects for growth are undermined by increasing pressure on its natural resources. The World Bank suggests macro-economic recovery and stimulus packages be combined with structural measures that will sustainably increase productivity and build resilience to enhance livelihoods, the economy and general well-being.

Uganda’s poverty problems, however, predate the pandemic. In 2016/2017, the poverty headcount ratio increased to 21.4 percent as per the UNHS. This implies that the number of poor people increased from 6.6 million in 2012/2013 to 8.03 million in 2016/2017.

The observed increase in the headcount poverty rate was a setback to the progress made during the last decade. It also jeopardised the likelihood of achieving the NDP II or the second national development target of reducing poverty to 14.2 percent by 2019/2020.

What is clear is that the pandemic made a bad situation worse. Whereas in 2019/2020, the headcount poverty rate decreased to 20.3 percent, the proportion of the labour force deprived of productive employment increased from 17.8 percent in 2016/2017 to 37.9 percent in 2019/2020.

Trail of destruction

The challenges the healthcare sector faced during the pandemic showed that there is a need to improve access to and effectiveness of emergency responses (ambulatory services) and referral systems. UNHS’s latest report recommends the swift establishment of a national health insurance scheme to increase access to quality healthcare in the aftermath of the pandemic.

The researchers observed that whereas the government funds education in government-aided schools, completion rates remain low. To compound matters, the pandemic disrupted schooling after education institutions were left under lock and key for a long period.

A number of private schools also closed shop after the pandemic showed no end in sight.

On the mend?

Uganda’s economy has exhibited signs of resilience. According to the Bank of Uganda, the economy is forecasted to grow at five to six percent in 2023, despite external shocks by the war in Ukraine and high food and energy prices globally.

Mr Robert Migadde, the vice chairman of Parliament’s Committee on National Economy, nevertheless believes the lack of political will by the government to get Ugandans out of poverty could worsen the poverty dilemma in the post-pandemic era.

“Even if Covid-19 wasn’t there, poverty was there and has been increasing. We should not be blaming Covid-19 or the informal sector.” Mr Migadde told Saturday Monitor, adding that attempts by the committee to advise the government on deliberate strategies to alleviate poverty in Uganda keep falling on deaf ears.

The Buvuma Island County lawmaker says the government doesn’t seem to rate the reports “we produce on the performance of the economy” highly.

“The contradiction is that when the government is introducing programmes to boost the people’s incomes, it also increases taxes, and that makes its efforts meaningless because the same population will remain in poverty because their incomes go to taxes,” he reasoned.

Oil boost?

In the Financial Year 2021/2022, Uganda Investment Authority (UIA) licensed a peak figure of 631 projects with a planned investment of $5.44 billion. This leap in licensed investments is attributed to the impact of post-pandemic recovery and the impending planned oil and gas projects.

However, such gains continue to be threatened by the high fertility rates that translate into pressures on the environment and household savings for investment.

The increasing climatic changes affecting agricultural production and livelihood sources for 62 percent of the population haven’t helped matters.

UIA also says the decade from 2012 to 2021 was characterised by several events of significant economic impact, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the Uganda-Rwanda border closure (2018 onwards), and persistently high fiscal deficits since 2015.

While Uganda’s growing economy is expected to experience growth in demand for services across most, if not all categories in the post-covid-19 era, UIA observes that a critical investment constraint is observable in some sectors like transport services, land, and air.

“Inadequate skills are a cross-cutting constraint to growth in the stock of professional services providers. Increase investments in skills development (to improve the stock of employable people and productivity) to overturn the trend,” the UNHS report recommends.

It also proffers an increase in investments in skills development to improve the stock of employable people and productivity.

“One key area is that the government also needs to review the tax regime and investment incentives regime to attract more labour-intensive industries,” the UNHS report notes, adding, “In the long run, revenues from labour-intensive industries may grow to offset the trade-off in slow job creation capital-intensive industries.”

Poverty

Before the pandemic, poverty rate in rural areas stood at 20.58 percent as per the Uganda National Household Survey 2019/2020 data. During the pandemic, it increased to 26.86 percent. Meanwhile, in urban areas, the increment was from 11.2 percent to 11.9 percent.