Prime

Kanyomozi: The cooperatives’ trailblazer and political stickler

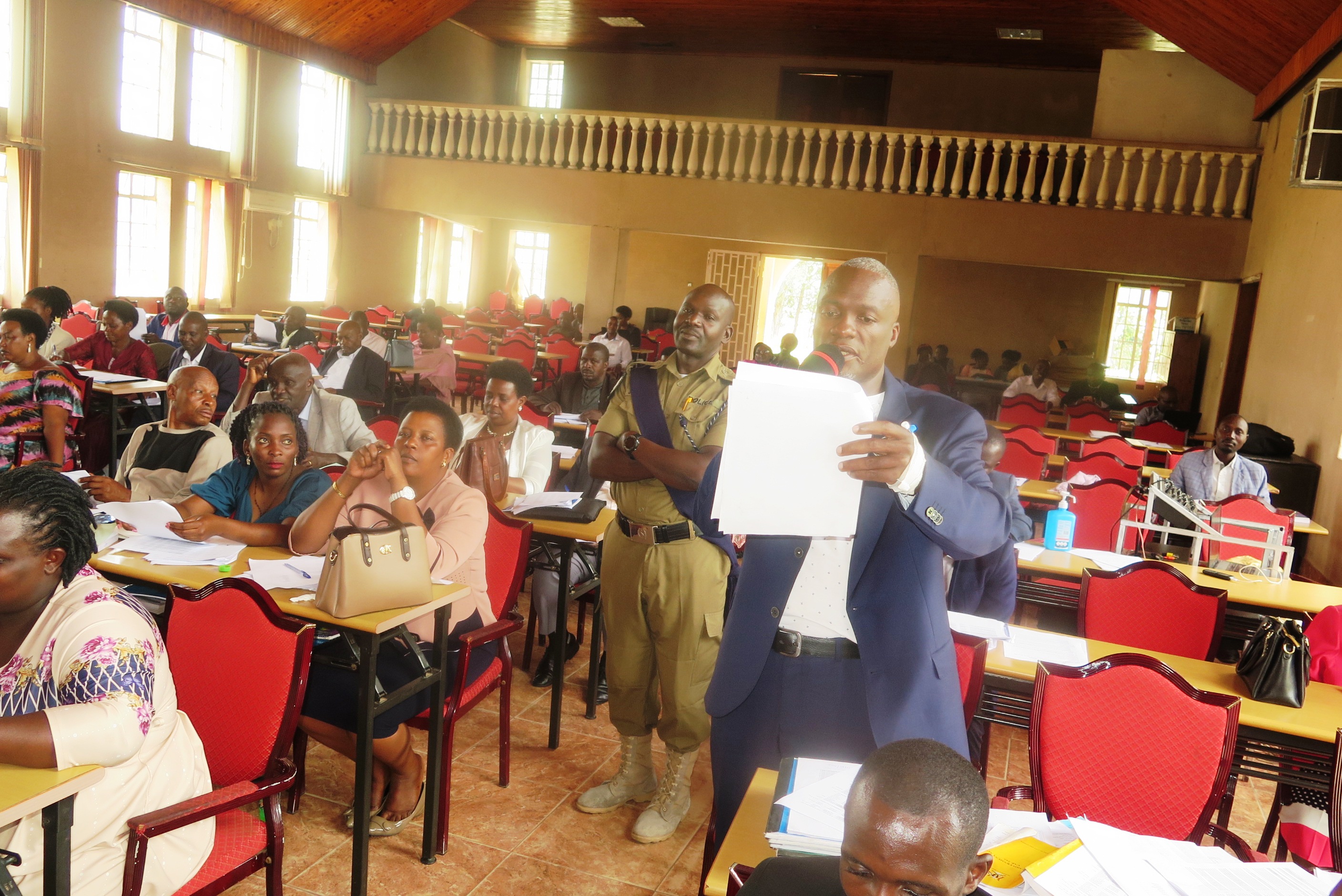

Deputy Speaker of Parliament Thomas Tayebwa (left) and other mourners during the requiem service of the late Yona Kanyomozi at All Saints Cathedral Nakasero, Kampala, on August 31, 2022. PHOTO | DAVID LUBOWA

What you need to know:

- The man who remained Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) party stalwart till death was on the verge of writing his autobiography, working on it with Mr Ivan Okuda, a journalist-turned-lawyer.

Yona Kanyomozi, 81, a former minister of Cooperatives, who died at Nakasero Hospital in Kampala on Sunday, has been hailed as a “principled politician”, who stuck to his beliefs regardless of the risk.

Relatives, friends, compatriots and leaders of different pedigrees gathered at All Saints Cathedral Nakasero yesterday to eulogise a man who, as minister in Milton Obote II’s government, became the ideologue of cooperative movement.

At the time, coffee and cotton were prized cash crops and forex earners and organising rural farmers in groups and cooperatives, alternately then called societies, bolstered their power to bargain better prices from buyers.

Such empowerment, which fizzled out when cooperatives atrophied under the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party government, which is struggling to kick the defunct entities back to life, is nostalgic for Uganda’s older generation.

Kanyomozi, fondly called Yona, was the face of cooperative movements’ successes in yesteryears. And he was steadfast, when he had power, and after Obote lost it.

At the funeral service yesterday, Kampala Assistant Bishop Hannington Mutebi said many politicians change depending on their interest, but Kanyomozi was principled.

“We don’t have many [people like him] today,” he said.

Kanyomozi died of cancer on Sunday.

He was born to Zakayo Bwanungu in Kibatsi Sub-County, Kajara County in present-day Ntungamo District in 1941.

Bwanungu was a wealthy cattle farmer.

The man who remained Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) party stalwart till death was on the verge of writing his autobiography, working on it with Mr Ivan Okuda, a journalist-turned-lawyer.

The working title of the draft book is: On life; one man’s journey through the alleys of Uganda’s politics.

When Kanyomozi was young, the British were recruiting youth to join the army before they would be deployed to fight in the Second World War.

Among the youth targeted for conscription were Bwanungu’s two children.

Bwanungu had lost two sons before 1941. He didn’t want his two youthful remaining sons to be conscripted into the army. The option of avoiding conscription for his two sons was to travel to Buganda, Uganda’s populous region, to toil as labourers.

Although labour provision in Buganda was seen by members of his community as a greener pasture, Bwanungu despised it.

He didn’t envisage his children working in someone’s garden.

Another tragedy struck him. The cows that provided livelihood began dropping dead one after the other, plunging him into poverty.

According to Kanyomozi, the tragedies tormented his father that he picked up habits such as smoking the pipe, which he had abandoned when he joined the Christian Revival Movement as a born-again Christian.

Kanyomozi’s mother resorted to tilling to earn a living to keep the family afloat.

Joining school

In 1947, a school band moved around their home looking for children to enrol. His mother enrolled him. Kanyomozi’s father was opposed to anything that connected his family to western lifestyle.

He preferred his children to look after cows as theirs was then, as is now, a pastoralist community. But his mother insisted that her son should enrol for formal education given the fact that they no longer had many cows as before to preoccupy him.

He started from Rukoni Church School. It was later renamed Rwesingo Primary School.

The pupils wrote on the ground. As they advanced to higher classes, they were given slates.

He then moved onto Kitunga Primary School.

His mother did everything in her means to help him continue with education that at one time she escorted him every day because the school was far from their home.

“My mother was a woman of extreme courage and determination. In 1952, stray lions visited our area [and] we were all terrified, yet we had still to go to school. My mother decided that she would accompany me until day break, especially when our class was on duty and I did not stay with relatives near the school,” Kanyomozi noted in accounts in the draft book.

“Fortunately, the lions were hunted down by the locals and the Saza Chief who had a gun shot one of them and [we] regained our normality.”

In December 1953, while he was in primary 5, his father died.

He completed his primary six class, which was the limit for primary schooling. He performed well and got a bursary with the help of Muntuyera, the father of Opposition politician Gen Mugisha Muntu, who previously served as army commander. With a bursary under his belt, Kanyomozi sprinted to Mbarara High School where he was exposed to future prominent citizens such as Mzee Boniface Byanyima who taught them history.

He would later join Ntare School among pioneer students.

Being a less privileged student, he used not to return home during holidays. He used that time to do menial jobs at school to get extra income.

In 1957, he got his first trip to then Uganda’s capital, in Entebbe, and visited State House.

They had gone to pick a piano that had been donated to the school by Sir Andrew Cohen.

The former Energy minister, Mr Richard Kaijuka, who studied with Late Kanyomozi, said yesterday that Kanyomozi was a very bright student.

“He was one of those brilliant students as Ntare School was emerging as a government school. When people did Cambridge School Certificate, eight people earned themselves distinction in English language. …Yona distinguished although he was from Ntungamo,” Mr Kaijuka said.

Kanyomozi didn’t have shoes, yet he was studying with students that wore some of the best brands available in the country.

He refused to apply to join Makerere University because the school’s alumni didn’t inspire him. He wanted to join Royal Technical College in Kenya.

Mr Kaijuka said Kanyomozi ended up in Nairobi, Kenya.

US study

He applied for a scholarship in an American university. He got a placement in Lincoln University, where he studied for a year. But when he visited late Aggrey Awori, who was studying at Harvard University, he felt that the university where he was studying wasn’t of the world-class quality he wanted.

He reapplied for change of university. He was told that it would be impossible, but he persisted.

Kanyomozi got admission to three universities. London School of Economics in UK had the most favourable conditions.

He worked in a garment factory for some time to get enough funds to enable him travel from the United States to the United Kingdom.

After getting the funds, he made it to the UK. Education life in London needed him to have supplementary income.

He got a job in a bar and worked as a waiter for some time before he was promoted to a supervisor.

In the UK, he engaged himself in emancipation politics that at one time they invited Malcom X, a black rights activist in the US, to talk to them in UK.

In 1963, he joined UPC and was elected the party’s secretary for the UK and Northern Ireland chapter. He was just 22 years old.

After completing his education, he participated in European politics for a short time and returned to Uganda after securing a job at oil giant, Shell.

At the Entebbe International Airport, he was nearly stripped naked as the security personnel searched him. They suspected him of being a communist.

Later, late Godfrey Binaisa, who was then Attorney General, accommodated him after several companies refused to offer him a job.

Binaisa connected him to a friend Erisa Kironde, who was the head of Uganda Electricity Board. Kironde appointed him as his personal assistant.

He worked in UEB until 1970. In 1968, UEB facilitated him to study a Master’s degree in Managerial Economics at a university in London. When he returned, he applied as the director of Industrial Development Centre. He got the job.

Milton Obote was toppled as the President of Uganda and Idi Amin took over. Things turned for the worse for Kanyomozi. He was detained at Makindye military barracks. Upon release, he planned for his exile through Malaba border and fled to Nairobi with his children. In Kenya, he got a job in a telecom company. He used his job to help fight Amin’s government.

Links to NRA

On Monday, this week, President Museveni said Kanyomozi was one of their contacts in Nairobi who helped them during their armed struggle despite belonging to UPC.

He returned to Uganda after Amin was removed.

During the short-lived Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) government, he was appointed the Minister of Cooperatives, a portfolio he held under Obote’s second government.

Kanyomozi was a politician of many feathers, and he threw his hat in the political ring, winning Bushenyi South parliamentary seat.

From 1989 to 1996, he represented Kajara County in the National Resistance Council, the Parliament in early years of the ruling NRM.

His last attempt in politics was in 2011 when he stood in Ntungamo Municipality. He lost the election and retired from politics.

Ms Maria Obote, the widow of Milton Obote, said Kanyomozi loved his party, the UPC, and remained in it until his death. He is survived by seven children and many grandchildren.

Kanyomozi will be buried tomorrow in Rwashamirire in Ntungamo District.