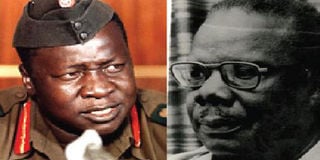

Muwanga plays cat and mouse with Idi Amin

What you need to know:

- There has always been contention about Muwanga’s political role in the 1970s, after president Idi Amin took over office in a coup. Perhaps one of the most damning accusations about him is that he looted Uganda’s Embassy in Paris, France. However, in our last part of the series, Ephraim Muwanga, the politician’s son, says his father compensated by providing logistical support to Ugandan rebels in Tanzania.

- When Muwanga reached Paris, his family and embassy staff thought he was a ghost because they had heard reports that he was dead. Amin reportedly called the embassy and asked Muwanga how he had left the country and the latter told him he was doing his (Amin’s) work.

With president Idi Amin sure of his position in February 1971, he invited Paulo Muwanga to help him constitute his Cabinet. First, Amin offered Muwanga the position of minister of Foreign Affairs.

“My father told him his health was not robust and yet Amin needed a younger man to justify the coup to the world. Amin then asked him to suggest someone for the job. Naturally, my father looked into his SAPOBA contacts and chose Wanume Kibedi, Amin’s brother-in-law,” Ephraim Muwanga says.

Muwanga and Kibedi then constituted the Cabinet of the military government, and after the initial murders of Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) and former president Apollo Milton Obote’s supporters, Muwanga was the brains behind the president’s announcement that the violence against UPC members should stop. He also gave initial assurances to the United Kingdom and Israel that the new government would not follow Obote’s path (socialism).

Struggle for recognition

In late 1971, Obote in Tanzania was still a thorn in the side of the new regime. Amin had yet to win recognition by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) states. According to Mr Ephraim, Amin had needed a seasoned diplomat to head Uganda’s delegation to an OAU summit in Somalia. He chose Muwanga and sent Kibedi to tell him of the appointment.

“Dad developed cold feet. He hated military coups. There was no way he was going to defend a military regime to [Tanzania president Julius] Nyerere or Rashid Kawawa, his personal friends, even though he hated Obote. He told Kibedi to tell Amin he was feeling weak but he would join the delegation after a few days.”

Due to his aggressive survival instinct, Amin suspected Muwanga was up to something. When he returned from Mogadishu, he met with Kibedi.

“Kibedi defended my father, saying he was aging. He, however, came home and warned Muwanga not to wait for the consequences of Amin’s suspicions. He advised him to take up the vacancy left by Ignatius Barungi, who had resigned as ambassador to France.”

The next day, Muwanga was on a plane to Paris. Kibedi told Amin he had ‘exiled’ Muwanga to Paris.

Life in Paris

Muwanga had acquired expensive tastes. Before he drunk from a glass, he first tapped it to hear its clink, to determine its quality. He wore expensively tailored suits. At the embassy, everything was substandard, including the furniture. He immediately summoned Alice Kamugisha, the head of chancellery.

“He told her he could not work in such an environment. He could not even sit in the chairs. They had given him tea on a tray that was not the same colour as the cups. He told her the embassy and ambassador’s residence had to be refurnished. Kamugisha did not have funds for that activity. Dad told her to take stock of all the furniture and put it in storage because he was going to furnish both the embassy and the ambassador’s residence using his own money. He even ordered for the latest model of Citroën (the SM) as the ambassador’s car.”

With Muwanga running the embassy, Paris became the centre of anti-Aminism.

“Everyone who was anyone in the struggle passed through Paris; even the one who said Amin ruled him for one day. Those who wanted passports and money run to Muwanga and he provided both through a separate office he was running clandestinely in the embassy. But Amin soon found out about the secret office. One of the men Muwanga had saved from Kampala at the risk of his own life, was working in that secret office. He is the one who betrayed him.”

In August 1973, Muwanga attended an international conference and on the sidelines, held a press conference. A journalist asked him why his government was killing its civilians.

“He replied that nobody was being killed. That was propaganda. The guerrillas fighting the government were killing people. Then, he told the journalist: ‘If I were to answer you as Paulo Muwanga, I would tell you that the information you have (about the killings) might be, sadly, true.’ State Research Bureau (SRB) agents at the embassy immediately filed a report to Kampala.”

Before long, the ambassador was recalled and he knew his case would end in a public execution. He began preparing himself. He bought a flat in London on Stratford Broadway, a residential house in Kent and enrolled his younger children in London schools. He also bought a set of cars.

“The letter summoning him to Kampala, in October 1973, also invited the military attaché, who was an Acholi man, and Kamugisha. Since he had staffed the foreign affairs ministry with his people, my father always knew what was happening in Kampala. Even the minister of cooperatives, Mustafa Ramathan, a Nubian, passed information to him. When the letter came, dad called Sheikh Ali Senyonga in Egypt (a former member of external wing of defunct Uganda National Congress) and instructed him to travel to Paris.”

Muwanga handed over his family, London property and cheque books to Sheikh Senyonga, telling him if things went astray in Kampala, he should take care of his family.

“One of my sisters called (Godfrey) Binaisa asking him to plead with dad not to fly to Entebbe, but dad was adamant, saying: ‘We cannot all run away. I must tell this man point blank about what he is doing to the country.’ Binaisa pleaded with Muwanga, telling him not to leave him (Binaisa) with the responsibility of his children.”

As Muwanga and his escorts got to the airport, he had a surprise in store. “He had bought a second air ticket. There was a six hour difference between the two tickets. The Acholi military attaché refused to leave Paris, fearing that he would be killed in Entebbe. Muwanga, Kamugisha and the SRB agents checked in. Because my father was flying first class (boarding through a different gate), the agents did not notice that he did not get on the flight.”

Muwanga jetted into Entebbe on an evening flight on October 10, 1973, way past Amin’s office hours.

“His SAPOBA contacts had taken care of everything. They transported him from the airport to Kampala International Hotel (now Sheraton Hotel). After checking in, he went out to meet (Lt Col) Juma Oris (minister of information and broadcasting). Oris was surprised to see him, and asked why he had returned. Muwanga knew the next day Amin was travelling to Algeria for the Non-aligned Summit conference. When Oris told Amin that his ambassador was in Kampala, he left instructions for Muwanga to await his return.”

According to Mr Ephraim, his father left Oris’ office in a kitengi, yet he had entered while wearing a suit and spectacles. From October 11 to October 22, Muwanga remained in Uganda, although SRB agents failed to find him.

“He never travelled in one car for more than 5kms. He lived at the home of a Muslim friend, Hajj Kayizi, near Kajjansi Mosque. The SAPOBA family worked out the logistics that kept him safe.”

On October 22, 1973, Amin and Muwanga met in the President’s Office. It was just the two of them in the room for one and a half hours.

“He wrote about that meeting in his notes, which are in London. He only told us that when Amin told him people were accusing him of being a guerrilla, he told him: ‘Your Excellency, the same people are saying you are killing Ugandans.’ Both agreed that the information against them was mere propaganda. Amin invited him to address a joint press conference but he declined, saying he needed to rest. When Muwanga left the office, he entered the president’s car and instructed the driver to drive to the airport because the president had sent him on urgent business. No one dared stop him. By the time Amin sent his men to our home, dad was airborne. They ransacked our homes in Kololo, Gayaza, and Kagoma, looking for him.”

When Muwanga reached Paris, his family and embassy staff thought he was a ghost because they had heard reports that he was dead. Amin reportedly called the embassy and asked Muwanga how he had left the country and the latter told him he was doing his (Amin’s) work.

“My father told the embassy staff to pack the property he had bought with his money. He also asked them to pay his dues (salary). Kamugisha did a stock taking and dad’s property was shipped to London. The only things Muwanga stole from the embassy were all the new passports and the stamp used in renewing passports. Those passports and that stamp benefited all those who were fighting against Amin. Interestingly, none of them talks about it today.”

Life in exile

Muwanga handed over the embassy to (Michael Akisoferi) Ogoola and flew to London. “My father had become rich from the coffee trade. The flat he had bought had three floors – the ground floor had his fish and chips shop and the first and second floors were rented out as offices and apartments, respectively. He told us life had changed and we had to adapt to it. The fish and chips business thrived and mom and my sisters were also doing kyeyo (casual jobs). By 1978, Muwanga was a wealthy man having opened up companies that supplied anything on earth – except oxygen – to all corners of East Africa.”

Muwanga in Tanzania

Struggle to overthrow Amin

On November 20, 1977, Amin issued a directive for Muwanga and other ministers who had defected to be brought back to Uganda dead or alive to face criminal charges.

At some point in 1977, Muwanga travelled to Yugoslavia seeking support to oust Amin. Unconfirmed reports say he set his fish and chips shop on fire and claimed the insurance money (when he became a powerful vice president, Muwanga imprisoned the man who accused him of this fraud).

“With no business holding him in London, in 1978, Muwanga moved to Tanzania to join the armed struggle to oust Amin when the Obote leadership had given up and resigned into drinking.”

Mr Ephraim and his older brother were living and working in Tanzania, on a World Bank project.

“We felt at home in Tanzania. Dad used to come and go as he pleased. All the 22 exile groups knew that he was their benefactor. He visited the different camps, providing social amenities and food from his own pocket.

He flew all over Europe and America meeting different people for the cause (toppling Amin). The (David Oyite) Ojoks saw him as Muwanga the Ugandan, not Muwanga the Muganda. My brother, who was living in Dar es Salaam, was well known to the exiles.”

Muwanga worked hard to convince Ugandan Muslims in Tanzania that the exiled community did not blame them for Amin’s atrocities. He assigned Shiekh Ssenyonga to speak to the Muslims through Radio Tanzania. Shiekh Ssenyonga broadcast his message under the pseudonym ‘Sheikh Muzzafaru Mukasa.

Mr Ephraim, however, declines to discuss the conspicuous role of his siblings in the Ugandan rebel camps in Tanzania.