Prime

The bitter sweet life of an exhumer

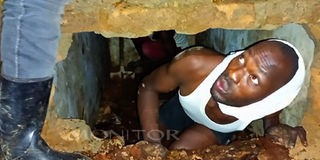

Mr Jacob Kizza during an exhumation. He has been doing the job for eight years. Photo / Courtesy

What you need to know:

- Chapter 13 of the Penal Code Act, Clause 120 and 121 stipulates measures against disturbing the peace of the dead. However, in the never-ending fight between cultural norms and the need to develop land, caretakers of the dead are caught between a rock and a hard place. Gillian Nantume spoke to Jacob Kizza about what it feels like to mint millions out of exhuming bodies for a living.

At 34, Jacob Kizza is an unassumingly rich man unlike most of his agemates. He, however, likes to keep a low profile, maybe because of the nature of his job.

Kizza is balding prematurely, and heavy drinking is beginning to take a toll on his facial features. Before any exhumation, he drinks three 750ml bottles of dry Gin.

Skeptics may say the dead do not speak. But Kizza believes they talk to him – in his dreams.

“When I am going to exhume a body, its spirit will not talk to its relatives. Instead, he or she will appear in my dreams. In the dream we sit down together and have a civilised conversation about what is going to take place,” he says.

It is a job shrouded in the mist and fog of myths. At 1pm, on a hot Friday, we stand behind one of the bars at Kumbuzi, seven miles out of Kampala City, on Gayaza Road. Kizza and his colleagues are about to slaughter a goat, as is the norm before any exhumation. As the meat sizzles on the fire, Kizza takes a swig from his new bottle of Gin - the second of the day.

“I have to drink to chase away the fear; to get the courage to open up a grave. I never get drunk though,” he says.

By midnight, the party is done. Armed with a court order, they set off for the grave site and at 1am, exhumation begins.

The men use a spade to shovel away the soil and create a way for the coffin. Then, with pick axes, they break open the cemented area. One of them gets into the grave and pulls out the remains. It is an eerie sight. Bones and bits of cloth are transferred into an awaiting coffin.

And by 4am the remains are exhumed. Tomorrow, they will relocate them.

Setting out on this job

Kizza left his village in Masindi District 12 years ago in search for a better life in the city. He has been exhuming and relocating the dead for eight years. At first, he worked as a garbage collector and porter and later joined a funeral management company. That experience triggered him to create his own company, Kalipiro Grave Masters.

He employs 12 workers and whoever participates in an exhumation is paid Shs1 million. His first exhumation was in Mukono District, seven years ago.

“The person who was supposed to direct us to the grave got scared and just pointed to us in a general direction. We dug up the place but did not find a body, so we just put soil in the coffin and transported it to Busia District. However, the deceased appeared to his relatives in a dream and told them we had cheated them. So, we had to go back to Mukono and exhume him,” he says.

On average, Kizza carries out three exhumations every two months.

He charges Shs10 million for an exhumation in and around Kampala. The charge skyrockets to Shs14 million shillings for exhumations outside Kampala.

The costs cover transport, purchase of a new coffin, new clothes for the remains - whether they are whole or just bones, digging, and finishing the grave at the new site. Nowadays, he also carries out exhumations in South Sudan, Kenya and DR Congo.

Business is usually conducted over the phone. However, before hiring new workers, he warns them of the challenges.

Challenges

“Before an exhumation, we have to bathe in traditional medicine. Sometimes, we find snakes in the grave. Sometimes, you do not know how the deceased met his death. He might have been murdered and his spirit is still angry. However, some of my workers are skeptics and do not follow my advice. Two of them have died and others have suffered car accidents because of their skepticism,” he said.

Besides some clients who cheat him, Kizza has faced some challenging processes.

“The scariest moment for me was opening up a grave and not finding any remains. Then, the deceased spoke to one of my workers in a dream, telling her we had come at the wrong time. He told us to return the next day at midnight, and indeed, we found the body in the grave. This was in Kyegegwa District, and we had been warned that some evil elements there use the spirits of dead people to dig in their gardens.

He added: “Another time, in Masaka, as we were just starting to exhume a body, a terrible, cold wind came out of nowhere and blew... A drunkard who was watching nearby told us the deceased had been a witchdoctor. It took us three days to exhume that body, and yet, to-date, four years down the road, the woman who hired me has never completed my payment.”

Kizza, who says he never gets scared of any exhumation, moves with an old rosary in his car. The rosary had been buried with a man they exhumed. However, in the rush to rebury him, they forgot his rosary. He claims the man’s spirit kept bothering him – to pacify it – he decided to hang the rosary in his car.

Achievements

From the proceeds of this job, Kizza has built rental houses in Kawempe Division, and is now constructing a storied house in the village for his mother. He, however, reveals that his mother does not know the job he does. In addition, he owns six cars and four bars around Kampala.

His achievements, although, seem not to have brought him happiness. Kizza does not have a wife, and does not expect to get married. He has a four-year-old son whom he has brought up on his own.

“Sometimes, when I am tired after an exhumation, I take the body to my house, sleep, and then continue with the relocation the next day. How do you think a wife will react to me bringing a body home? How will she tell her mother that, ‘My husband brings bodies home?’” he asks.

Kizza, who is Catholic but hasn’t been to church 12 years, says he does not have friends.

“None of the guys I hang out with can accept an offer of beer from me. They fear my money. In fact, one of them said that even if I buy him a brand new car, he can never drive it,” Kizza says.

He adds: “There are many bars around this place and the bar maids cooperate and exchange beers whenever they run out of cold ones. However, I have a deep freezer, but no one comes here to exchange beer. No one even comes here to ask for change, in case they have a big banknote. They would rather cross the road to other shops.”

As a precaution, he only visits his other bars at night, and only for a few minutes. The barmaids at the joint here at Ku Mbuzi did not last more than a week. On the day we conducted this interview he had hired a new barmaid. During the interview, she sat a few feet away, listening to Kizza’s story.

When we went back after one week, she had quit the job. Now, a young man runs the bar. But, how long will he last?