Apolo Kaggwa: The colossus of Buganda

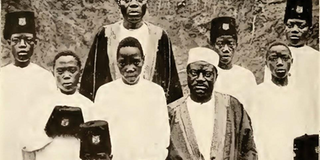

Apolo Kaggwa (seated) with some members of his family. The British at one time suggested that Kaggwa become king but Buganda rejected the idea. courtesy PHOTO.

What you need to know:

The transition from a collection of monarchies into a republic called Uganda owes a lot to the work Katikkiro Apolo Kaggwa did in collaboration with the British.

HIS LIFE

1865. The year Apolo Kaggwa was born.

1890-1929. Was Katikkiro (prime minister) of Buganda under Kabaka Mwanga’s reign.

1884. He was also food distributor and chief of royal stores when he joined the palace.

1897-1941. He was infant Daudi Chwa’s regent.

He is considered Buganda’s first and foremost ethnographer

Kaggwa’s writings and books

Entalo Za Buganda (The Wars of Buganda)

Basekabaka be Buganda (The kings of Buganda) Ekitabo Kye Empisa Za Baganda (The Book of Traditions and Customs of the Baganda) Ekitabo Ky’Ebika bya Abaganda (The Book of the Clans of the Baganda) Ekitabo Kye Kika Kye Nsenene (The Book of the Grasshopper clan)

When he joined the royal palace around 1884, Apolo Kaggwa was a mere food distributor among royal households. But by 1900, he was undoubtedly the most powerful person in Buganda, holding the kingdom’s present and future in his hands.

That rise to fame and might, according to some, is because the Katikkiro used his position to enrich himself and deprive those whose interests he should have espoused. His supporters say Kaggwa was progressive and played a vital role in thrusting Buganda and Uganda from the old, feudal world to a ‘modern’ western-style nation-state.

Although little information is available on Kaggwa’s early life, available records show that he was intent on becoming successful and at whatever cost. M. S Kiwanuka, who translated into English Kaggwa’s book- The Kings of Buganda, explains that when his parents sent him to stay with a relative - the chief of Ekitongole Ekisuuna, Kaggwa seized the opportunity to befriend the caretaker of the royal mosque, who helped him join the palace as a page.

Climbing the ladder

As an apprentice, Kaggwa’s eyes were set on the administrative opportunities that would come along. Three years after joining the palace, Kaggwa was the chief of royal stores, a position that gave him an interaction platform with several people, including Christian missionaries.

As an early Christian convert, Kaggwa had a safe chance to climb the leadership ladder, especially among Protestants, whom he would later offer his strategic collaboration service.

As the British sought to dig their colonial claws deeper into Uganda’s society and economy, collaborators became the effective tool to be used against their own, including the Kabaka Mwanga and later Daudi Chwa.

When Mwanga was ousted in 1888, he owed his reinstatement to the throne on October 5, 1889 to his Protestant backers, who had in a convenient alliance with the Catholics, helped dethrone Kabaka Kalema. Kaggwa had led one group of the fighters against Kalema’s men, and Semei Kakungulu, led another team.

However, Prof. Lunyiigo says Kakungulu, whose men delivered actual victory, were, despite their efforts, demoted in the ‘Kaggwa administration’. Kaggwa, who had by then become a darling of the Protestants, especially Capt. Frederick Lugard, would be given the power to run Buganda, under a puppet Kabaka- Mwanga.

“The Abalyabulo, Apolo Kaggwa, Stanislaus Mugwanya, Alex Ssebowa and Yona Wasswa actually took power. Mwanga did not participate in the appointment of officials of his government. He was no longer a free agent; it is very likely that the protestant missionaries, now calling the shots in the protestant camp, influenced the appointments…,” says Prof. Lunyiigo.

The Kabaka, who was supposed to be the ultimate figure of authority, became a subject of Kaggwa, a man groomed in the palace but his loyalty for the Kabaka diluted by religion and a desire for survival in the colonial-managed Buganda.

“Mwanga begged Apolo Kaggwa to have Kakungulu appointed Pookino but he could not hear of it. Instead a big protestant personality, Nikodemu Ssebwato was appointed Pookino to the important province of Buddu and Kakungulu was relegated to the relatively unimportant post of Mulondo in the frontier country of north Kyaggwe..,” Prof. Lunyiigo adds.

When Mwanga’s authority was clipped more by the British, through the signing of an agreement by IBEAC, which gave the British certain rights over revenue, delivery of justice and trade in Buganda, the Kabaka was tired of being humiliated by the British and by Kaggwa who was now the real power.

The British had even suggested that Kaggwa becomes king but the Baganda would have none of it. “It was suggested in 1892 by the British that Kaggwa should become Kabaka but the Kaggwa dynasty failed to emerge. The Baganda were still very too strongly tied to the royal bloodline to allow Kaggwa to establish his dynasty,” writes Prof. Lunyiigo.

Mwanga’s failed revolt against the British in July 6, 1897, and his final defeat on January 15, 1898, would ensure the embedding of colonial claws in Buganda, but also become a period for great reward, through land to the collaborating class, where Kaggwa belonged.

When infant King Daudi Chwa was enthroned to replace Mwanga, Kaggwa would become one of the King’s three regents but easily the most powerful. On behalf of Buganda, Kaggwa signed the 1900 Buganda Agreement that, among others, removed sole land stewardship from the Kabaka, and gave more than half of Buganda’s productive land to chiefs and notables.

The dishing out of land under the 1900 Buganda Agreement seems to have been the peak of satisfaction for Kaggwa’s political career. It also allowed him to go on and accumulate a private estate of 100 square miles, sometimes using less-than-noble means.

Having had a key influence in the negotiating of the terms of the Agreement, Kaggwa received £300 from the Protectorate Government for the 10,550 square miles it took over (Other regents and the Kabaka also received money).

‘Land grabber’

However, even with that allotment, some historians accuse Kaggwa of grabbing land from the lowly in Buganda then, including a 13-square mile Bussi Island in Lake Nalubaale that was occupied by the Nvubu and Nnonyi clans.

“Magera sent Apolo Kaggwa the biggest Ssemutundu (cat fish) and bunch of Matooke Kaggwa had ever seen,” Prof. Lwanga wrote. “This was exactly the time Kaggwa was looking for land to claim and he coveted Magera’s island and took it turning the chief mutaka (land overseer) into a squatter.”

Numerous reproaches seem to weigh on Kaggwa shoulders, but credit must be accorded to the Buganda’s longest-serving Katikkiro for his strides, especially in keeping alive the kingdom’s history through his writing.

R.P Ashe in Chronicles of Uganda notes that by 1894, the 29-year-old Kaggwa had already written a book – Entalo Za Buganda (The Wars of Buganda). Even though some historians tag Kaggwa’s writings to inspirations he derived from the literary environs provided by the missionaries, credit cannot be withdrawn for the more than five books he wrote about Buganda.

Historian M. S Kiwanuka says of the Katikkiro’s writings: “The general conclusion one would draw is that enough evidence has been collected to demonstrate that Kaggwa can be trusted in much of what he wrote. He had access to sources which have since been lost, and he managed in the circumstances of the time, to produce respectable and largely trustworthy account of the country’s past.”

He adds: “Everyone interested in Buganda’s past, be it a historian or not, will remain in Kaggwa’s debt. His influence on Kiganda historiography has been tremendous, and would be unwise today to accept any information independent of his.”

His falling out with the British, over beer, no less, ended a stellar political career and discarded to the dustbin of history a man who had played a key role in shaping that of his kingdom and his country.

Continues tomorrow