Ochana, Arnold: The men who made Akii-Bua

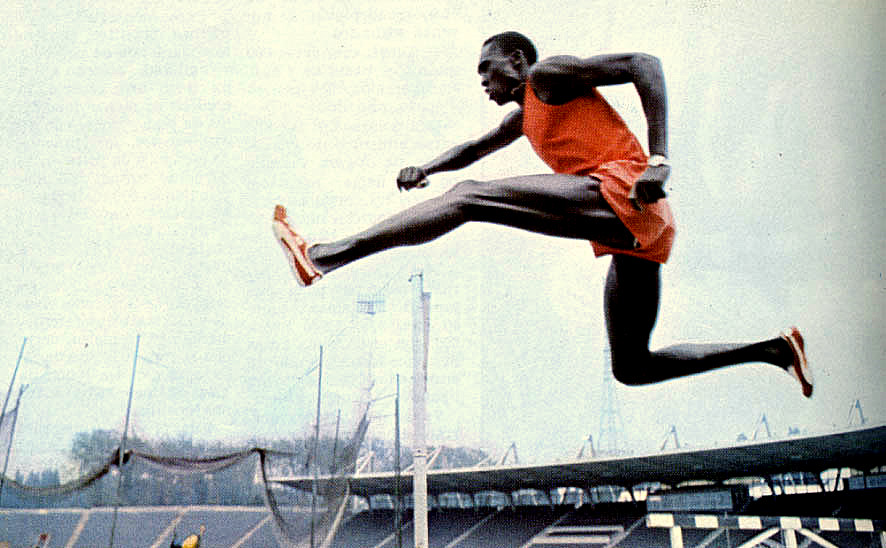

John Akii-Bua was Uganda's first Olympic Gold medalist. PHOTO/COURTSEY

What you need to know:

Saturday, September 2, 1972, 16:15, the Final. Nowadays, winners in the preliminary rounds choose which lanes they will run in in subsequent rounds and logically, they choose the friendly middle lanes. Akii-Bua didn’t have that privilege and ran the final in the hard Lane One.

Malcolm Arnold OBE is 82. Retired. After coaching at an enviable 13 Olympic editions, 11 of which with the UK national athletics team, which attracted honours from the Queen.

But all this greatness started in Uganda, 54 years ago. And Arnold will never forget his first ever Olympic champion, John Akii-Bua, who won the 400m Hurdles gold and set a world record at the 1972 Munich Games.

“Of all the athletes I have worked with, I put John number one," Arnold told David Conn of the Guardian in 2008. "He came from very poor circumstances, living in a hovel while working as a policeman. We worry today about the technology of drugs; he struggled for one square meal a day. From there, his achievement was incredible."

But Arnold did not start from scratch. Akii-Bua was a work in progress.

Ochana, the unsung hero

Akii-Bua was one of over 40 children born to Yusef Lusepu Bua, a county chief in Abako, Northern Uganda, who lived “a legendary life” having married nine wives.

But after his father’s death, the family struggled to fund Akii-Bua’s education.

In his mid-teens, Akii-Bua sought better fortunes in Kampala. Since colonial times, the army, prisons and police were the epicentres of sports in Uganda. No wonder, most of the stars of the country’s golden generation belonged to the forces, where discipline, hard work and a sense of patriotism—factors behind every sports success story—were the norm.

That talent development strategy continued through the Amin regime before it died under Museveni’s privatisation.

Akii-Bua joined the Uganda Police Force. The training regime and facilities at Nsambya Barracks were conducive. Inter-forces competition was high. At Police, he met Jerom Ochana, the hero seldom mentioned in Akii-Bua’s widely told biography.

A high-ranked police officer and athletics coach, Ochana was also an established athlete, especially in the Hurdles.

At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Ochana finished fourth with 52.4sec, in the third quarterfinal heat of the 400m Hurdles, and failed to make the semifinals. He also held Africa’s 440 yard-hurdles record holder. He imparted his skills to Akii-Bua.

Before specialising in Hurdling, Akii-Bua was a versatile track and field athlete.

"Can you see this scar on my forehead? Ochana…made me listen. I used to bleed a lot in our exercises, knocking the hurdles with my knees and ankles, keeping my head down," Akii-Bua told Sports Illustrated, November 20, 1972, emphasising Ochana’s direct influence on his formative Hurdling years.

That Ochana and Akii-Bua spoke Luo eased their communication and made the coach-athlete bond stronger.

Welcome Arnold

When you mention Akii-Bua, 1972 is the year that easily comes to mind. It’s natural. Ends outlast means. But 1968 is such an important year for both Akii-Bua and Arnold.

By March 1968, Arnold was a physical education teacher at Rodway School in Bristol and a part-time athletics coach. But in October the same year he was in Mexico City coaching Team Uganda at the Olympic Games.

He was only 27, but when his application to coach abroad succeeded, the father of two didn’t think twice about a journey that would nurture him into legendary success.

Soon, Arnold became Uganda’S coaching director, introducing modern training methods, including tracking athlete's performances in: strength and stamina; speed, sharpness and technique in phases over a year.

By then Akii-Bua was an athletics all-rounder. He would also win 110m Hurdles gold at the 1969 East and Central African Championships in Kampala. But Arnold sensed that Akii-Bua lacked the explosive speed for short sprints and could do better at the gruelling 400m Hurdles.

Convincing him was not easy, nor was the transition. And Akii-Bua didn’t qualify for the 1968 Games, where Uganda won its first Olympics medals, both by boxers.

Two years later, at the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, Akii-Bua lost in the semifinals of the 110m Hurdles but finished fourth in the 400m Hurdles as teammate William Koskei took silver.

Since then Akii-Bua, under Arnold’s programme, worked with undivided focus on the 400m Hurdles. Climbing hills in a jacket loaded 12kg, repeating 600m runs, resting for just a minute, almost every morning and afternoon. He jumped hurdles much taller than the competition heights. Prior to the Olympics Akii-Bua had high-altitude training in the hills of Kigezi, in south-western Uganda, enduring the rampant rains. His improvement was tremendous.

Conquering the world

Ahead of the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Akii-Bua had posted some notable victories, but had never met top class hurdlers like defending Olympic champion David Hemery of UK and American favourite Ralph Mann.

But no one could stop the debutant from making history. First, Akii-Bua won the preliminary heats, while Koskei, his former teammate, who had reversed his nationality to Kenya and was rated above him, dropped out.

Finally, Akii-Bua had to test himself against the best: Hemery and Mann, in the semifinals of Heat One.

He had won the preliminaries in the unfavourable inner lanes—One or Two. Same case in the semis. But he overcame that hurdle as well, winning in 49.25 seconds—the fastest time in both semi-final heats. Mann came second in 49.53sec, Hemery third in 49.66sec, while West Germany’s Rainer Schubert, qualified in fourth. If that was a fluke, Mann and Hemery had the chance to show us in the final.

Saturday, September 2, 1972, 16:15, the Final. Nowadays, winners in the preliminary rounds choose which lanes they will run in in subsequent rounds and logically, they choose the friendly middle lanes.

Akii-Bua didn’t have that privilege and ran the final in the hard Lane One.

But “Akii-Bua was amazing,” wrote Kenny Moore, who finished fourth in the 1972 Olympic Marathon, in a Sports Illustrated article: ‘A Play of Light,’ November 20, 1972. “As other finalists in the hurdles stared blankly at Munich’s dried-blood-red track, grimly adjusting their blocks and minds for the coming ordeal, Akii danced in his lane, waving and grinning at friends in the crowd.”

Perhaps he was trying to shake off those horrible visions of Hemery winning, which had given him a sleepless night before.

The footage shows that most of the focus was on Hemery, who started at a searing speed, taking the lead in the first 200 metres. But long-legged Akii-Bua was steadily catching up and overtaking the field with ease. After the final turn, Hemery had slowed down, surrendered the lead to Akii-Bua, who jumped and sprinted to the tape in 47.82 seconds—a new world record. Like in the semis, Mann came second, Hemery third. Akii-Bua was now an Olympic champion, Uganda’s first.

In his celebration, he ran to the man behind this monumental victory. "When I finished my victory and demonstration jog, I met the coach Arnold," he wrote, according to the Guardian. "His sight exalted my excitement and made me collapse and I briefly wept."

Both coach and athlete had helped each other to a great conquest, one which will be cited forever. Not forgetting Ochana’s initial input.

Wrong turn

However, fate would soon break the Arnold-Akii-Bua bond. The expat trainer returned to the UK in 1972, to knit an illustrious career coaching Great Britain in 11 Olympic editions and several world championships, until his retirement in 2016.

But Arnold doesn’t forget his roots. Often, he has admitted that working with top athletes and coaches in Uganda “has definitely been a development experience for me.”

Conversely, Akii-Bua didn’t return to the Olympic podium, due to mostly political disruptions. American Edwin Moses broke Akii-Bua’s world record at 1976 Montreal, which Africa boycotted. While in exile, Akii-Bua lost the semi-finals of the Moscow 1980 Olympics due to poor preparations. He returned to live a less enviable life, before dying in 1997, at just 47.

AKII-BUA CAREER BRIEFLY

Born: December 3, 1949

Semifinal: September 1, 1972

Gold: September 2, 1972

Died: June 20, 1997 (aged 47 years)