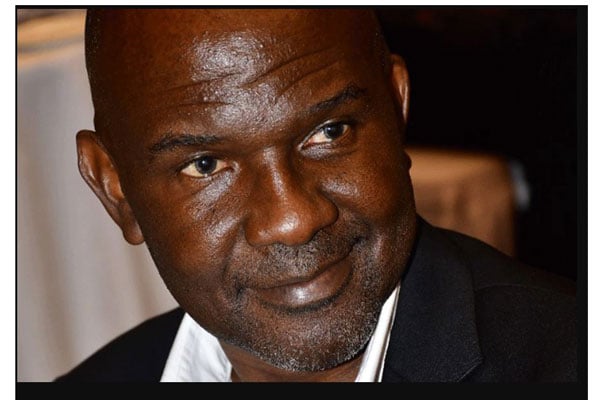

Mr Odrek Rwabogo, the chairman of the Exports and Industry Advisory Committee (PACEID)

It’s a hot, merry afternoon. And I am meeting him at Serena hotel. He is super excited about his search for new markets for Uganda’s exports mostly in Europe and Asia. A developing country like Uganda needs outside markets for its produce because exporting goods to international markets brings in foreign currency, which is crucial for economic stability and growth.

This foreign exchange can be used to purchase essential imports such as machinery, technology, and other goods not produced domestically. And relying solely on the domestic market can be risky due to fluctuations in local demand and economic conditions. Exporting to various international markets helps diversify risk, ensuring that economic downturns in one market do not severely impact the overall economy.

But for local traders to have their produce meet the standards of international markets, they often need to improve their production techniques, quality control, and packaging. This can lead to overall improvements in the agricultural sector, benefiting the local market as well. Followed to the letter, a country like Uganda can attract foreign direct investment (FDI). Investors are often more willing to invest in countries with proven access to large markets, ensuring their investments have the potential for growth and profitability.

Charismatic

When we first meet, Mr Odrek Rwabogo, the Chairman of the Exports and Industry Advisory Committee (PACEID), exudes a calm charisma. He is grounded and brimming with knowledge about commerce and advertising. He tells me that PACEID is working hard to research new markets and close deals for Ugandan companies because it is difficult to sell to a market you do not know.

“Nobody goes to the garden unless you have already thought of the market for your produce, and things like how they will buy it and when, because all these things go into account to determine the price of your product,” he says.

“You can only answer those questions if you do market research in the places where you place your food and other productions. And it’s not about humongous bills. Even just a deep stick survey of who consumes our products, why, when, and what packaging you are doing to attract them,” he adds.

So far the entity has gone to seven African markets and four have come on in agreement.

Mr Rwabogo and his team counsel Ugandan businesses on what products to sell and to whom to sell them whenever a new market arises.

“I hope people know that countries meet each other at company level,” he says, adding that wealth is created at company skill level and then diplomacy and other things happen.

Doing homework

In a conference earlier, he had explained this.

Although it is cool, he claimed that meeting presidents and ambassadors to discuss trade agreements does not really help like most people think. He maintained that in order to find markets overseas, such as in Serbia, one should speak with the procurement departments of these companies, as well as their wait staff and business managers.

It’s because these are the individuals that make purchasing decisions for hotels and determine what supermarkets should stock on their shelves and in what locations.

Mr Rwabogo stated that this should come first, followed by the diplomatic ties, and that is why his team has been concentrating more on it.

“So those seven markets where we have done surveys, we bring them on, we try to bring trade representatives on so that we are able to sell,” he says.

“Fortunately, we started with African Free Trade Area countries. In Europe, there are places we have opened trade hubs that have some coffee, vanilla, and if we did not have delays, we would replicate the model at Entebbe airport so that people are able to see what products they should buy as they leave the country, but what products should people buy in those countries? We have done a lot of work in media, hubs, and research,” he adds.

Trade snapshot

Uganda’s producers are increasingly getting cash from the export markets. Figures from the central bank show that in March 2024, export earnings grew 61.8 percent to $7.127 billion (Shs26.5 trillion), largely attributed to gold exports.

With the exception of gold, exports rose by $433.3 million (Shs1.6 trillion) as a result of favourable weather, better trade relations, and somewhat better terms of trade as the price of commodities declines globally.

Most of Uganda’s exports are coffee, Tobacco, oil re-exports, base metals and products, cocoa beans, gold, fruits and vegetables.

The private sector’s increased imports of machinery, gold, and oil for investment caused imports to rise by 28.0 percent to $10.257 billion (Shs38.1 trillion), even though export receipts increased by more. With gold excluded, imports rose to $7.885 billion (Shs29.3 trillion), a 0.9 percent increase.

The trade balance increased by 13.3 percent to $3.129 billion (Shs11.6 trillion) in the year ending January 2024 as a result of export growth exceeding import growth.

NTBs

Mr Rwabogo worries about the non-trade barriers (NTBs) that the region at times squabbles with. He nevertheless exudes confidence that there are bigger things to look forward to.

He argues that since the East African region is Uganda’s largest market for goods, NTBs that prevent Ugandan goods like milk, poultry, sugar, beef, and maize from reaching that market indicate that the region lacks the cohesion and strength necessary to share a common dashboard. Kenya, for example, is Uganda’s largest trading partner but mounts most of these NTBs.

“In 1988 when I was joining senior five, we were importing soda, bread and milk. Today we have spread those countries in the region. This creates space as the forces of demand even out poor production practices, technology. But I’m not too fixated about the problems we have in the region because they are small potatoes compared to bigger problems of getting our companies to compete and supply products in the global value chains,” he says.

“I would be worried about the EAC speaking together to ECOWAS and SADC and the three of us talking to the China market and the US market. That’s what matters because now we are going as countries but I don’t think that grows us in the long run. Regional blocs speaking the same language regardless of the issues they have internally is what will get us into those big markets,” he adds.

Baby steps are being taken. At least bilaterally. In a communiqué, President Museveni and his Kenyan counterpart instructed their trade ministers to address these NTBs, claiming that they still hinder trade between the two nations. They also “directed the ministries responsible” to create the mechanisms for putting the signed Memorandums of Understanding into effect.

Challenges

Mr Rwabogo faces a significant challenge due to the lack of coordination among various institutions that support exports. Each institution operates within its own mandate and jurisdiction, making unified efforts difficult. He believes it will require substantial effort to establish a central hub that can effectively coordinate these activities and advocate for our exporters.

Another issue is securing orders but failing to meet them due to insufficient quantities or not meeting the quality standards demanded by the markets.

“But this is a temporary problem. We are trying to solve it by creating associations of production in consortium. We set up one in sim sim in the Lango area. And we will progressively fix those problems,” he says, adding that people need to believe that they can compete on the global market.

Another bottleneck he has encountered “is that some markets are open to us but closed, like one that asks standards that companies in my country cannot meet.” This, he further explains, is akin to “giving you the market with one hand and taking it away with the other.”

ESG investing

The European Union (EU) has introduced a new policy aimed at curbing deforestation by regulating the import of certain commodities, including coffee, into its market. The policy requires that all coffee imported into the EU be sourced from supply chains that do not contribute to deforestation.

Exporters to the EU market are therefore required to demonstrate traceability and conduct due diligence to prove that their coffee supply chains are deforestation-free. This involves providing detailed information about the origins of the coffee and the production practices used so that they comply with the EU’s rigorous certification and verification processes for its standards.

Non-compliant imports can be subject to penalties, and companies failing to adhere to the rules may face fines or bans on their products. Mr Rwabogo has urged Ugandan entities to step up to the plate and comply with the new rules. It is, he adds, in the best interests of all parties, not least in the age of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing.