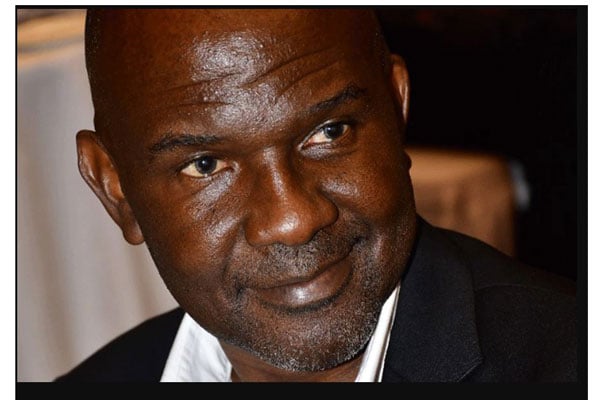

Author: Moses Khisa. PHOTO/FILE

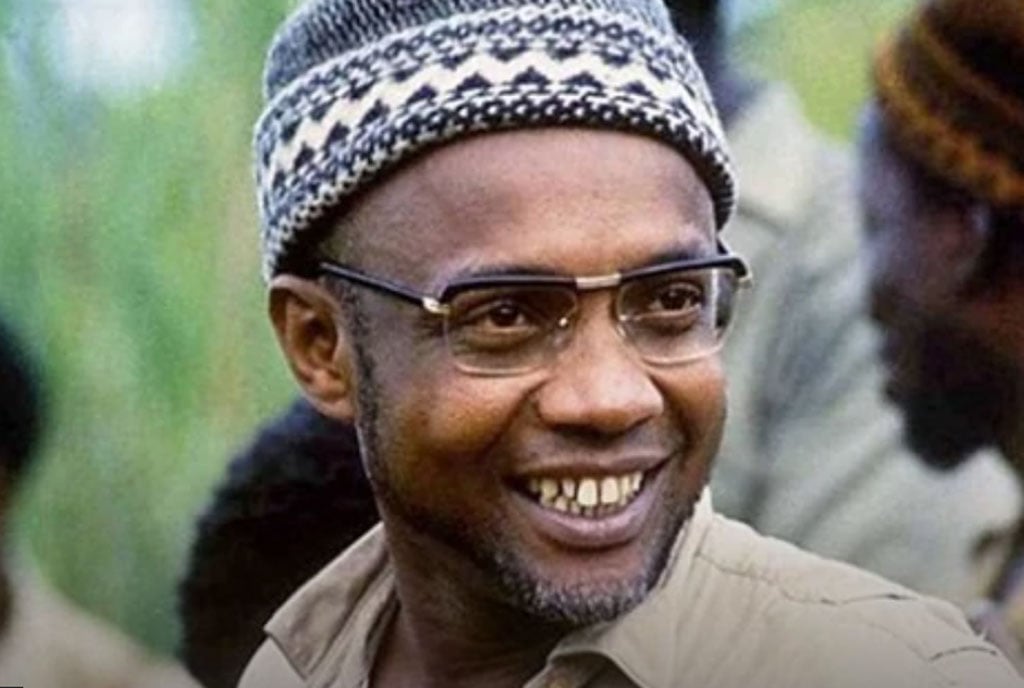

Amilcar Cabral was the heroic commander of a successful anti-colonial insurgency in the then Portuguese Guinea and Cape Verde. In 1960, he founded PAIGC, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde.

The acronym PAIGC taken from Portuguese. He launched a people-powered anti-colonial struggle in 1963. By the time he was cowardly assassinated in January 1973, supposedly by his own men but allegedly at the behest of his Portuguese nemeses, the latter were effectively defeated on the battlefield despite their superior military capabilities and tens of thousands of troops.

Cabral displayed first-rate strategic foresight and clarity of thought, a master tactician in guerrilla warfare, especially how to fight a truly people’s protracted armed struggle.

His praxis drew from a fine grasp of revolutionary theory interspersed with a deep appreciation of the material circumstances and social conditions in which guerrilla rebellion was executed. After a decade of matching the Portuguese in combat, gradually gaining an upper hand in controlling most territory, even with his dastardly murder, Guinean independence was nigh, a matter of time.

Stretched in battle and staring at humiliation by an otherwise ragtag African guerrilla outfit, the Portuguese military turned on the authoritarian regime in Lisbon, the Estado Novo, which had ruled the country for more than 40 years under dictators Antonio Salazar and Marcelo Caentano.

In April 1974, just over a year following Cabral’s assassination, Portuguese soldiers overthrew their civilian bosses in Lisbon. This singular act was propelled by a grim battlefield outlook and faltering counterinsurgency against guerrillas in Guinea but also in the other two major Portuguese African colonies, Angola and Mozambique. It had far-reaching ramifications.

The coup in Lisbon precipitated not only the independence of Angola, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and Mozambique, it also set off a democratisation wave from Portugal and Southern Europe, then across the Atlantic to Latin America and further afield to Africa.

In designing insurgency against a formidable enemy, Cabral placed the people at the centre. He situated his war strategy in the cultural context of Guinean people. The people were everything, so their social and cultural circumstances and beliefs shaped how the PAIGC prosecuted the armed struggle and practiced its politics.

Embedding insurgency among the people, and providing ‘rebel governance’ in liberated zones, became the default strategy for the other liberation movements in Angola and Mozambique. It was especially the template emulated by later rebel groups in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Uganda from the 1970s to 1990s.

Pan-African revolutionary Amílcar Lopes da Costa Cabral. PHOTO/FILE/COURTESY/African Skies

For Cabral, national liberation and freedom were not mere abstract goals, rather they meant very concrete and material conditions of the masses. It was not just about defeating the Portuguese, it was fundamentally about organising the means of production and mobilising the masses for social transformation bearing in mind the unique features of agrarian society.

It was Cabral’s vision for Guinea and Cape Verde to gain sovereignty as one nation despite the latter astride nearly a dozen islands in the Atlantic. But once out of the picture, the two went separate ways as independent nations but also practically in their post-independence political trajectories.

The half-century of Guinean independence has been at best dispiriting and at worst tragic, an utter insult to Cabral’s spirit and the extraordinary sacrifices he made, ultimately paying with his life. In this travesty, the betrayal of all that Cabral stood for, last month there was a military coup d’etat, not for the first time.

Previous coups did not bring about actual liberation for the people that Cabral fought for, the latest is unlikely to be any different. Like most military coups in post-independence Africa, this too was a cheap power grab, made even more despicable by credible suspicion that it was stage-managed to subvert the will of the people at the polls.

By many accounts, those in power seized power from themselves to stop it from slipping away to their opponents through elections! For what it was worth, incumbent President Umaro Sissoco Embalo was carted off to Senegal, then to Brazzaville. Before his departure, as he was supposedly being ‘overthrown’, he had the freedom to speak to international media, announcing the coup! Incredible.

Military coups and military-style regimes have scarcely been the solution to Africa’s governance problems. If anything, as I have argued in this column before, coups, countercoups and failed coups have done more to hurt than help the cause of accountable and responsive government in post-independence Africa.

From 1950 to 2023 there were 109 successful coups in Africa, representing nearly half of all coups worldwide. Looked at carefully and closely, case-by-case, most of these coups were little more than power grabs by self-seeking elites in the military, state intelligence and political circles.

Countries that have experienced coups and been under military regimes fared poorly on a range of indicators, from political stability and democratic governance to economic performance and overall social wellbeing of citizens.

Last month’s coup in Bissau is the type that would likely prompt Cabral, had he been alive, to launch a truly people’s protracted struggle for national liberation.