President Museveni. PHOTO/ FILE

|People & Power

Prime

How corruption scandals have bedevilled NRM govt over the years

What you need to know:

- With Uganda no longer a Western darling, President Museveni, who has been in power since 1986, has for the umpteenth time claimed that he is going to use every weapon within the armoury to see that he stamps out corruption from his government. Derrick Kiyonga looks at his record in fighting corruption.

During the debate that led to the second passing of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, former minister of Ethics and Integrity James Nsaba Buturo painted a picture of how corruption has affected Uganda’s independence in terms of making decisions or laws.

“What we steal from ourselves is three times more than what we get from those arrogant people around the world,” Buturo said in an apparent dig at the West that has threatened to cut aid should President Museveni sign the Bill into law.

Buturo made the statements days after Museveni used the Labour Day celebrations in the eastern district of Namutumba to say that he was going to come up with another anti-corruption unit inside State House.

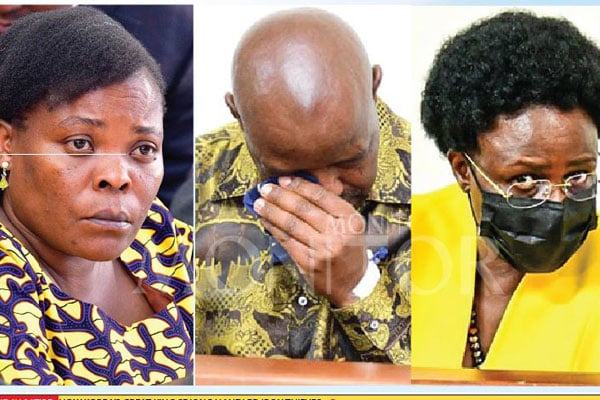

Against the backdrop of the Karamoja iron sheets scandal which has seen three ministers – Mary Goretti Kitutu (Karamoja), her deputy Agnes Nandutu and Amos Lugoloobi (State minister for Planning) – charged, Museveni said he would forge a body that is ostensibly devoted to combatting bribery in public offices.

“I am using this Labour Day to tell everybody that we are going to have a big fight. I am going to set up another small unit in my office where the investors can ring directly if anybody asks them for a bribe or delays decisions,” Museveni said.

L-R: Agnes Nandutu, Amos Lugoloobi and Mary Goretti Kitutu. PHOTOS/ABUBAKER LUBOWA

When Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) shot its way to power in 1986, there were some attempts such as crafting the Constitution that included institutions that allegedly would ensure that there are crucial checks and balances.

Key pillars in institutional development included Parliament autonomy and Judiciary independence.

The emergence of the new constitutional order came, at least on the face of it, with guarantees of public accountability through a number of organs that ranged from Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee to the Inspectorate of Government (IGG) and the Auditor General.

Despite putting in place such institutions, corruption has been on an upward spiral in Uganda with the February report on the corruption perception index released by Transparency International ranking Uganda at 142 out of 180 countries globally.

In the region, Uganda is the fourth most corrupt country in the East African Community (EAC) where it has maintained a score of 26 for the past two years after it fell from 28 in 2019. – Uganda trails South Sudan, Burundi, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Uganda has also scored poorly in the World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). In 2011, it scored 19.9 on control of corruption, on a scale from 0 to 100 and it has shown no advances across the years.

At the centre of the NRM’s alleged fight has been the Office of the IGG, which is charged with providing, supervising, investigating cases of corruption, issuing reports of investigations, issuing bank inspection orders, issuing witness summons, issuing warrants of arrest, and, inter alia, authorising prosecutions.

By 2009, Museveni had appointed three IGGs – Augustine Ruzindana, Jotham Tumwesigye, and Faith Mwondha. But it is Mwondha’s tenure as IGG that cast this office in the limelight.

Ex-Inspector General of Government Faith Mwondha

When President renewed her tenure in 2009, Mwondha refused to appear before Parliament’s appointments committee which was to vet her reappointment as IGG, telling journalists at a press conference that, “If God is for me, who can be against me”.

Once Parliament refused to sanction Mwondha’s reappointment, Museveni for years refused to appoint a substantive IGG, leaving Repeal Baku, then deputy IGG, to do the load lifting alone.

This arrangement soon ran into trouble when the Constitutional Court ruled that Baku couldn’t prosecute any cases involving abuse of office and corruption and causing financial loss because by acting alone in prosecuting the officials he was breaching the Constitution since the Inspectorate is not fully constituted.

By the time the Constitutional Court made the ruling in 2012, Baku had been acting IGG for two years because the President had not named a substantive IGG.

Soon, donors such as United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Africa Development Bank, which were pouring billions into the Inspectorate, closed their wallets, leaving the IGG’s office cash-strapped.

There was speculation on what exactly had led these donors to take this radical position, with many saying they weren’t happy with the way the “big fish” was getting away with corruption.

Even before he took power, Museveni had made a promise to fight corruption.

“Using government position to amass wealth is high treason. If UPM is not going to be supported because it denounces such methods of getting rich, let it be,” Museveni was quoted by The Ugandan Times, a government newspaper, on August 27, 1980. “Whether we form government in October or not, we shall leave no stone unturned; inculcating the right political consciousness in our people.”

Privatisation scandals

Later, this promise was buttressed in the NRM’s so-called 10-point programme with point seven emphasising the regime’s commitment to eliminate corruption and misuse of power. However, as the NRM’s regime was rolled into motion, this promise seemed to have remained on paper as from the onset the regime was entangled in scandal, after scandal with Museveni’s relatives, in some instances, being accused.

By the time Museveni’s ragtag rebel outfit wrestled power from Tito Okello Lutwa, records show that Uganda had 146 State-owned enterprises — 138 majority holdings and eight marginal state holdings.

It was in 1989, when at the behest of the International Monitory Fund (IMF) and World Bank, the privatisation drive went into motion with the sale of Nile Breweries, Shell Uganda Limited, and Lake Victoria Bottling Company, sold to crown beverages.

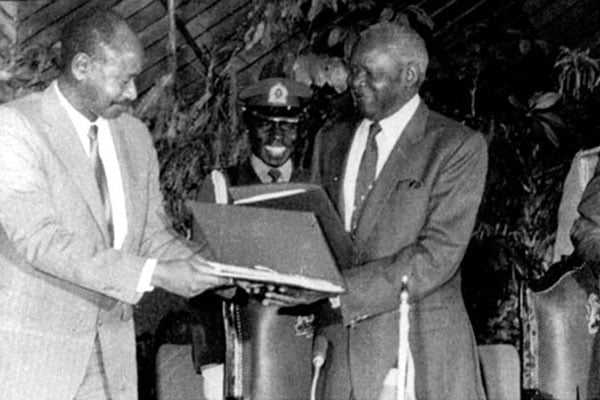

President Museveni and Gen Tito Okello Lutwa exchange documents during the Nairobi, Kenya peace agreement. FILE PHOTO.

The biggest corruption scandals in this privatisation crusade were revealed in the sale of the Uganda Commercial Bank (UCB), Entebbe Handling Services (ENHAS), and Uganda Grain Milling Company, in which Museveni’s kinsfolks were named in continuous investigations.

Before it was sold, UCB was Uganda’s largest bank with a total of 189 branches and held 45 percent of the total banking deposit. In 1997, the first move was made when UCB was initially converted into a limited liability company, meaning the owners weren’t typically held personally responsible for the business debts and liabilities.

In 1998 the bank was partially, 49 percent, privatised to a Malaysian company named Westmont Land.

A 2002 parliamentary inquiry revealed that Westmont mishandled the bank, triggering the Bank of Uganda (BoU) to act: It stepped in as the supervisor in November 1998 and later seized the bank in April 1999 before the expiry of the three-year management contract.

The investigation laid bare a number of jaw-dropping facts, including that Westmont had lent some Shs35b to Greenland Bank without proper securities and beyond limit levels and without consulting the Central Bank as the representative arm of government that owned 51 percent of the shares in UCB.

In April 1999, UCB was seized by BoU from Westmont and then re-privatised in 2001. Then, Greenland Bank was also closed. UCB was the largest bank at the time, on which Stanbic would later build its infrastructure to become one of the largest banks today.

In his book entitled Advancing the Ugandan Economy: A Personal Account, Ezra Suruma, Museveni’s former Finance minister, who was the director of research at the Bank of Uganda in the late 1980s, blamed UCB’s woes on Museveni and Gen Salim Saleh, his brother.

“The conflict over privatisation had an ideological basis. The President, following the advice of the World Bank, favoured it as part of the strategy to liberalise the economy… Parliament passed a private member’s Bill in May 2007 to keep UCB in State hands. Nevertheless, the government was able to go ahead.”

“It chose Westmont Land (Asia), a Malaysian company that made the highest bid, but also had a secret agreement to the front for a Ugandan bank in which the President’s brother [Gen Saleh] was a major stakeholder…” he wrote alluding to the report that Saleh, who is seen as the most powerful person after Museveni, had engineered the inappropriate seizure of 49 percent of UCB shares through a firm in which he owned majority shares, Greenland Investments.

Prof Ezra Suruma, Chancellor of Makerere University. PHOTO/FILE

In the case of Uganda Grain Milling Company, the highest bidder, Kenya-based UNGA Millers, was bypassed and the company sold to Saleh, under a company called Caleb International, on grounds of “Ugandaness”.

Even with these scandals, Museveni would in 2006 appoint Saleh as minister of Microfinance and he is now the chief coordinator of Operation Wealth Creation – a government programme run by soldiers and whose aim, in theory, is to mobilise communities, distribute agricultural inputs, and facilitate agricultural production chains across the country.

There was also the peculiar case of ENHAS. The company was in 1996 handed a monopoly of ground handling services at Entebbe International Airport.

Later, ENHAS, was sold neither to the highest bidder—Dairo Air Services— which offered $6.5m (about Shs25b) nor to the second highest bidder, South African Alliance Air which floated $4.5m (Shs17b).

It was acquired by then minister of State for Privatisation, Sam Kutesa, whose daughter, Charlotte Nankunda, is married to First Son, Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba.

Despite being censured by Parliament on the account of abusing the leadership code, Kutesa bounced back as Investment minister in the 2001 Cabinet. Later, Museveni promoted Kutesa as minister of Foreign Affairs, a position he held for 16 years.

Santana vehicles

Even before privatisation, NRM had been hit with corruption scandals with the perpetrators going unpunished. The major scandal before the 1990s involved Santana vehicles.

In 1988, the Uganda government wanted to purchase transport vehicles for the President’s office and the ministry of Defence.

Left to right: Uganda’s Finance minister James Simpson, minister of Justice Grace Ibingira, Prime Minister Milton Obote, UPC secretary general John Kakonge and US President John F. Kennedy during a meeting at the White House, USA, on October 22, 1962. PHOTO | COURTESY

Grace Ibingira, a former minister in the independence government who was now the Spanish Counsel to Uganda, brokered the barter deal with Spain and Uganda; the former would exchange ‘Land Rover’ vehicles for the latter’s coffee.

Ibingira had swayed Kampala that the Spanish-made ‘Land Rovers’ were as good as the British-made Land Rover.

However, once here, it was realised that the vehicles were not Land Rovers but Santana. Though they looked like Land Rover, they were smaller, weaker, and unstable on the road and their fuel consumption was twice as much as that of Land Rover.

However, in mid-1988, when Balaki Kirya, minister of State in the Office of the President in charge of Security, went to Spain to sign an agreement, he found 260 Santana ‘Land Rovers’ valued at $6.1 million had already been shipped while the agents/lobbyists were negotiating for the importation of another 260 ‘Land Rovers’ now valued at $8 million.

Parallel structures

With corruption eating up the fabric of society, Museveni said he no longer trusted the IGG’s office to lead the fight against corruption and he instead resorted to putting up parallel structures.

“When people start complaining about a watchman [IGG], then you have to hire another watchman to watch over that watchman and that is why I started and set up units in the President’s office to watch over the IGG,” Museveni rationalised setting up the State House Anti-Corruption Unit at the end of 2018.

With such pronouncements, Justice Irene Mulyagonja, the IGG at that time, decided to go back to the Judiciary where Museveni appointed her a Court of Appeal judge.

“I do not resign anyhow and I have only two years remaining to finish my contract. I still have a lot to do in fighting corruption. Some people present the front that we are not competent enough to investigate.

Maybe they think my officers are too junior to investigate them. Let the special unit [State House Anti-Corruption Unit], appointed by the President do the senior role,” Justice Mulyagonja said in a 2018 interview with Monitor.

When Mulyagonja eventually threw in the towel, it took two years for Museveni to appoint a new IGG. In 2021, he named Beti Kamya who had lost the Rubaga North parliamentary race, as the new IGG.

There was drama, however, in this appointment. Museveni first appointed Kamya as senior presidential advisor on lands, effectively consigning her into early retirement, but on second thought he appointed her IGG.

The drama continued once Kamya occupied office and she said that her first act was to introduce what she termed as a “lifestyle audit” on public officials that she said would curb the looting of public funds.

IGG Beti Kamya. PHOTO/HANDOUT

It wasn’t clear how Kamya was going to actualise this audit, but the whole idea was upended in 2021 when Museveni told her to go slow, lest the corrupt take their loot to outside jurisdictions.

“The lifestyle audit is good, but be careful because we are still lucky that our corrupt people are corrupt here. But if they realise that their lifestyle is being audited, they will instead take what they stole abroad and it will be hard to track them,” Museveni said during the 2021 celebrations of the International Anti-Corruption Day at Kololo Independence Grounds.