Prime

Inside NRM’s failed attempts at prosecuting ministers

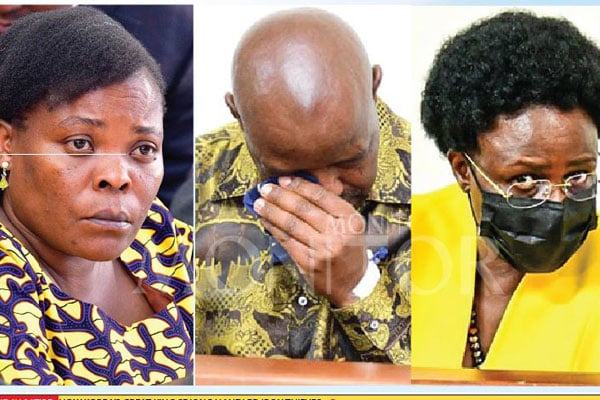

L-R: Agnes Nandutu, Amos Lugoloobi and Mary Goretti Kitutu. PHOTOS/ABUBAKER LUBOWA

What you need to know:

- In an effort to fight off criticism that in the fight against corruption in Uganda “the big fish” have largely been left untouched, President Museveni’s government has paraded a number of ministers before the Anti-Corruption Court.

It is not clear how many ministers will end up on the charge sheet following the fallout from the Karamoja iron sheet scandal which has seen ministers Mary Goretti Kitutu (Karamoja), her deputy Agnes Nandutu and Amos Lugoloobi (State Minister for Planning) charged. However, proponents of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) have been quick to claim the arraigning of the ministers as the latest indication that President Museveni is serious about fighting corruption.

“We also need to congratulate the President for his consistent fight against corruption. What I like about his communication is he has been clear from the start that all those involved have to be investigated,” former Uganda Law Society (ULS) president Simon Peter Kinobe, who is a member of the NRM, says.

David Mafabi, the senior presidential advisor on Special Duties was also quick to give Museveni credit: “[Mr Museveni] has been clear. He categorised it into political liability and criminal liability. What is clear is that he is not happy. He does not condone such practices. He has made a public statement, and we should wait. Beyond that would be speculation.”

From the time news filtered through that government bigwigs and Members of Parliament (MPs) shared thousands of iron sheets meant for the Karamoja sub-region through verbal communication and commands through WhatsApp, President Museveni has given directives to law enforcement agencies to take the matter seriously and for the politicians who took the iron sheets to return them.

“Those who diverted the mabaati [iron sheets] but not for personal use, must pay back the equivalent value in money or return the mabaati for the Karachuna, so that the programme goes on,” Museveni said in his April 3 missive to Prime Minister Robinah Nabbanja, who has also been implicated in the scandal.

“Those involved must both bring back the mabaati or equivalent value in money but also be handled by the police under the criminal laws of the country. I will also take political action once the police have concluded their investigations.”

Despite these pronouncements, Uganda’s history of prosecuting ministers accused of corruption leaves a lot to be desired, with the Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP) or the Inspector General of Government (IGG) so far failing to secure the conviction of a single minister.

In some cases, the evidence has been so weak that the ministers have been asked not to defend themselves after the State presented witnesses.

That was the case in 2011 when three ministers – Sam Kutesa (Foreign Affairs), John Nasasira (General Duties, Office of the Prime Minister), and Mwesigwa Rukutana (State for Labour) – were charged at the Anti-Corruption Court for allegedly causing Uganda a Shs14 billion loss in the run-up to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (Chogm) in 2007.

The IGG, who led the prosecution contended that a Cabinet sub-committee meeting on December 17, 2005, irregularly committed the government to fund projects at the privately-owned Speke Resort Munyonyo, thereby causing a financial loss of Shs14 billion.

Sydney Asubo, then a prosecutor with the IGG’s office, couldn’t believe it when the case collapsed before his own eyes as the key State witnesses instead defended the accused.

When James Mugume, then permanent secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, appeared in the witness dock, he told court presided over by Justice Paul Mugamba, that no meeting took place at Munyonyo on December 17, 2005.

“My Lord, the said meeting of December 17, 2005, which was a Saturday, is not anywhere in our archives among the series of meetings held in preparation for Chogm,” Mugume said, and with such evidence, Asubo was left stranded. At some point, Justice Mugamba had to calm him as he sought to declare his witnesses hostile, triggering laughter among court goers.

In dismissing the case, Justice Mugamba directed barbs at the prosecution.

“It has become fashionable for government bodies to present weak cases before courts. Clearly, the evidence assembled by the prosecution cuts no ice. It shows nowhere that the accused persons are culpable, so it wastes time, and resources and erodes the credibility of prosecution agencies,” said Justice Mugamba, who was left with no option but to acquit the trio.

ALSO READ: Agnes Nandutu: Troubled minister who miraculously became MP

DPP probes VP, 40 others implicated in Karamoja iron sheets scandal

The same fate befell the case in which the IGG linked former vice president Prof Gilbert Bukenya to irregularities in the procurement of luxury cars, which were used to transport dozens of heads of state during the Chogm summit.

The IGG’s case was that Bukenya connived and/or colluded with Motorcare Limited, awarding them a contract to supply 80 units of BMW R 1200 RT police outrider motorcycles intended for use during Chogm, without following procurement rules.

The IGG claimed that Bukenya and his alleged co-conspirators – Per Lundgren and Klaus Karstensen – the directors of Motorcare, caused Uganda to lose money to the tune of $3.9m.

After the IGG presented four witnesses, including Charles Muganzi, then permanent secretary in the Ministry of Works and Transport, the defence lawyers asked Justice Mugamba to dismiss the case on the account that the prima facie case hadn’t been made out and the judge obliged.

Before the judge could fully acquit Bukenya, who had spent eight days in Luzira prisons, the IGG admitted defeat and dropped charges of abuse of office he had levelled against the former Vice president.

There was also the failed trial of health ministers; Jim Muhwezi, Mike Mukula, and Alex Kamugisha, who had been accused of abuse of office, theft, embezzlement, causing financial loss, and making false documents in connection with the alleged misuse of Shs1.6b funds sent by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI).

The DPP alleged that on various days in 2005, the trio had dishonestly withdrawn billions in instalments from the GAVI Citi Bank account, part of which was meant to fund sensitisation workshops in Gulu, Mbale, and Bushenyi districts.

There was the usual script of ministers being taken to Luzira where they spend days before they get bail and are later acquitted without requiring them to put up any kind of defence.

“As for A1 and A3 (Muhwezi and Kamugisha), I agree with counsel submission that if there is no sufficient evidence shown that a crime has been committed, the court stops the case at this stage,” Irene Kankwasa, then a Chief Magistrate at the Anti-Corruption Court, said.

Of the three, only Mukula was convicted by Akankwasa, on finding that Mukula signed for the money, received it, and only returned it in three instalments.

“The accused refunded the money on May 17, 2005. This proved that he took the money that was part of the Shs263m he received,” Akankwasa said as Mukula shed tears upon hearing that he would spend four years in prison. “He intentionally took the money; that is tantamount to theft.

This prosecution victory, however, was short-lived since upon appeal, Mukula was set free after two months in jail. While acquitting Mukula, Justice David Wangutusi directly accused Muhwezi of being the mastermind of the theft.

In his analysis, Justice Wangutusi pointed out that the money came from Citi Bank, and the Ministry of Health’s under-secretary issued an order that the money should be given to Muhwezi instead of Mukula.

Though Muhwezi was now enjoying unfettered freedoms having been set free by Akankwasa, Justice Wangutusi mentioned a note Muhwezi wrote to Janet Museveni, in which the Luweero Bush War veteran said: “Please receive Shs54m as per our telephone conversation [in denominations of Shs50,000, Shs20,000 and Shs5,000]… kindly send me an acknowledgment of receipt.

“By the time a person writes a letter splitting the amounts in denominations, of the 50s, 20s, and 5s, he is most likely not only looking at it, but fingering it as well,” Wangutusi said.

The only conviction in this scandal came when Alice Kaboyo, then a State House aide, pleaded guilty to two counts of abuse of office and writing documents in the name of the former Private Principal Presidential Secretary, Amelia Kyambadde.

It was the prosecution’s case that of the Shs524 million allegedly advanced to Kaboyo to prepare advocacy conferences, she had already refunded Shs250 million. She was fined a measly Shs20 million but in 2021 she bounced back after Museveni appointed her as minister of State in the Office of the Prime Minister for Luweero Triangle-Rwenzori Region.

“In respect to the appointment of Hon Alice Kaboyo, after her conviction, the matter was considered by the Appointments Committee of Parliament, which approved her appointment. The Attorney General also gave an opinion to the effect that the law did not bar her from holding a public office. Therefore, her appointment was done in accordance with the law,” said Florah Kiconco, the head of the legal department, at State House as she tried to rationalise Kaboyo’s ministerial appointment in a recent rebuttal.

Former minister of works, Abraham Byandala, also had his day in court when he was accused of a raft of charges such as abuse of office, disobedience of lawful orders, influence peddling, causing financial loss, corruption, theft, obtaining money by false pretence, uttering false documents and conspiracy to defraud the government.

The charges were linked to the Mukono-Katosi road scam that cost the country up to Shs24.7 billion in losses. While acquitting Byandala, Justice Lawrence Gidudu, the head of the Anti-Corruption Court, blamed the IGG for drafting an incurable defective charge sheet which couldn’t be relied upon to secure a conviction.