Why the National Identification is good for your finances

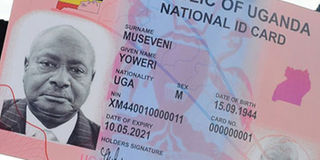

A dummy President Museveni national identity card shows how the documents are supposed to look like. File photo

What you need to know:

Introducing national identities would increase and enable financial inclusion coupled with financial education and low-cost financial products that are accessible for the poor.

The debate about the introduction of national identification is not a new one, and has been covered in previous fora.

The National Identification project is topical because it expresses concerns in several dimensions and is a key game changer in our nation.

The argument for national Ids is a simple one taking into consideration the benefits Ugandans would gain at the completion of this project.

Several reports have shown no progress whatsoever despite the amount of time and money invested in this project.

Why a national Identity?

Electronic national IDs will thwart cases of fake identification cards, which are so common in the country, being supported by our weak systems and the high levels of forgery. It would therefore bring about a standardised approach of identifying Ugandans from non-Ugandans.

This has worked well in countries like South Africa, where an ID number defines who you are and provides you access to cheap loans as a citizen. This is simply because the financial institutions can easily identify a local South African from a foreigner by use of the national ID.

Botswana is also planning to introduce an electronic National ID that will tighten the screws in order to minimise fake identification.

In many African countries, the identification of the poor citizens has remained a struggle.

They do not hold formal identify documents such as passports, drivers licenses, voters cards or birth certificates. And this is very paramount in accessing financial services.

Financial inclusion

Introducing national identities would increase and enable financial inclusion coupled with financial education and low-cost financial products that are accessible for the poor.

Research has proved that biometric identification has an impact on the behaviour of risky users of financial services.

There is better monitoring and tracking of borrowers in countries that have national Ids. The registration of SIM cards in Uganda recently was a highlight of the dangers of a lack of national Id system.

Requirements for registration were passport size photography, a completed form and a copy of an ID document.

Those with no formal IDs had to get a letter from the Local Council offices (LC) at a fee of Shs5000 or more which are prone to forgery and no verification of whether you were a resident of that suburb was required. Others had to use former employment IDs – no requirement to verify whether he or she is still employed with that organisation or not.

The objective of this registration was to enhance security of lives and property of Ugandans, protect the interests of those who are victims and potential victims of those who abuse the privilege of telecommunications.

One wonders whether these objectives will be achieved in the long run. This would have been the perfect approach on developing a database capturing all Ugandans in one system which would later be used for issuing of national IDs.

How effective can a national ID system be?

An effective ID system should have a verifying system, a database, a card and a card verifying system.

Without all the components of a national id working together, the card ceases to be useful.

Before implementing the ID project, there must be an assurance that the person receiving the card is who he or she claims to be.

In order to implement an ID system, there must be incentives attached to attract mass registrations or penalties imposed for not being registered.

Otherwise this would end up like one of the voting registrations that are boycotted by majority of the corporate and elite class.

Zimbabwe has a much more organised ID system in place. A unique individual number is printed on a birth certificate which is later used to obtain a national ID at an appropriate age. The same number will appear on all official documents like passports or voters card.

Without the ability to identify who qualifies to have a national ID in a country, then the objectives of this project would never be realised.

In Uganda today obtaining a passport doesn’t necessary require verification of citizenship. There are no means of proving that you are indeed a citizen of Uganda who qualifies for a passport.

A letter from an LC or a birth certificate doesn’t necessary mean that you are actually a resident of that area or a Ugandan as long as a fee is paid to obtain one.

The national ID system in its own might not be a game changer in terms of fighting crime, but would require the support of the police to hold random ID checks.

An online verification system accessible only to properly authorised personnel would do away with forgery.

In reality, we as Ugandans should expect the national identities to support financial inclusion for instance through mobile money , track the movements of criminals, bring about order in terms of identification and verification and also have more accurate population statistics among other benefits.

Finally, the government has done some work in this area and looking at the National Security Information System (NSIS) deliverables, it is important to have an assurance that this project would address the actual need and that once it is implemented, it will work as intended.

Troubled project

Idea born: The project idea was born in the 1980s where every Ugandan would hold a National Identity Card that would be acceptable for elections, to financial institutions, and travel within East Africa among others.

Outcome: Up to now, only 401 identity cards are said to have been issued and about Shs240 billion spent in a country of about 33 million people.

Irregularities: The IGG probe in 2005 established that the procurement process of the vendor, who would implement the project, was riddled with illegalities. The probe also found that the process was characterised by patronage and in-fighting by public servants who had vested and even competing interests in the outcome.

The author is Barbara Nantege, Standard Chartered Bank Africa Regional Head of Customer Due Diligence Risk