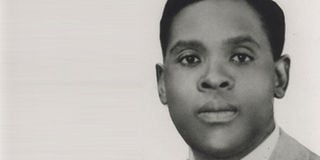

Ignatius Musaazi and the rise of African nationalism

Ignatius Kangave Musaazi was among the western-educated elites who started the demand for African participation in the colonial administration.

What you need to know:

The growing grievances by Africans towards the colonial State and the economic structures it created, paved way for the rise of men- who would lead the agenda for reform and political change.

Although he did not feature prominently in the independence governments, Ignatius Kangave Musaazi played a very significant role in the anti-colonial struggles. In fact, the history of the anti-colonial struggles cannot be complete without the mention of Musaazi.

This article will review the career of Ignatius Musaazi from the 1930s to the late 50s.

The 1930s was a period of relative economic decline throughout the colonies of Africa and this had major political consequences because the economic recession led to protests which constituted the beginnings of modern anti-colonial movements.

The depression pinched even harder because it occurred in the context of rising expectations based on the relative prosperity of the first two decades of the century, when the terms of trade were relatively favourable to Africa, and peasants and traders had profited. As a result of the depressed level of the economy and the resulting curtailment of the colonial services, disillusionment set in.

Two sets of different but related developments made this disillusionment particularly explosive. Not only had the representatives of pre-colonial polities - the chiefs and kings been absorbed into the colonial hierarchy as its most loyal collaborators, but the newly-educated elite, far from seeking to return to pre-colonial structures, sought to share in the administration of the new order.

Among those educated people were men like Dr J.B. Danquah of Gold Coast (later Ghana), Chief Obafemi Awolowo of Nigeria, and Ignatius Musaazi of Uganda. These were “the western-educated elite”, who having reached, and in some cases surpassed, the intellectual attainment of their colonial administrators, on the administrators’ own terms, began to demand participation in the administration.

It is this class of people who led the criticism of the colonial structures throughout Africa in the late 1930s. While in other African colonies such as Nigeria and Ghana, this situation constituted the anvil upon which the nascent countrywide national movement was forged, this was not the case in Uganda.

Both the uneven nature of colonial development which made Buganda a more developed enclave even politically then, and the rubric of “indirect rule” which carved out a separate political arena in Buganda, conditioned “an ambivalent nationalism not entirely divorced from parochialism” to develop alongside Buganda separatism.

As a result, political agitation in Uganda during this period was not only limited to issues affecting Buganda, but also geographically restricted to the kingdom. The main channel for this agitation was an organisation variously called “Sons of Kintu” “the Grandsons of Kintu” or “the Descendants of Kintu” formed on May 28, 1938. The chief organiser and Secretary of the organisation was Musaazi.

World War II breaks out

Ganda neo-traditionalist in ideology, the organisation had two main objectives: to direct the complaints of the farmers and merchants into channels where they would be heard; and to get rid of the government of Buganda then headed by Martin Luther Nsibirwa as Katikkiro.

Although the organisation failed to attain most of its objectives, it succeeded first in mobilising people in the countryside to a level which had never been attained in the colony before, and, secondly, in propelling Musaazi into a long political career.

The following year, the Second World War broke out. Although the colonial system looked impregnable at the beginning of the war, it did not take long for the war to take so heavy a toll on it that in a sense, the war became a major turning point in the liberation of Africa from colonial rule.

The war brought “about demonstrable changes in the attitudes of the colonial powers towards the way in which they had administered their African subjects and placed them on the defensive about empire; the war also wrought major changes in the consciousness of the colonised peoples.”

A major factor to put the colonial powers on the defensive was the rise to world leadership of both the United States and the Soviet Union, something that was largely conditioned by the war itself.

As the war progressed, there might have arisen an impasse or the Germans might have won, had the two powers not tipped the balance. This was to make the two powers very powerful.

The two new superpowers were, for totally different reasons, to oppose colonialism and add voice to the internal opposition in Britain. The war also provided conditions for greater internal opposition to colonialism in Britain: the Labour Party, for instance, gained immense strength when its leader Clement Attlee became deputy prime minister in a coalition government.

Apart from the effect the war had on the international context of colonialism, the war also triggered major changes in the domestic conditions of colonialism in Uganda. The medium for the war to cause far-reaching social transformations in Uganda was the participation of Africans in the war.

Africans were not only enlisted to fight the war, but Africa was a major source of supplies. The total number of Africans who participated directly in the war is estimated at 533,084 of whom, 76,166 were from Uganda. To most of these recruits who had lived in isolated villages hardly affected by the colonial government, common military service had the effect of propelling the recruit to transcend former ethnic barriers.

The period of total involvement with and dependency on an agency of the state had the effect of also inculcating in the recruit, a new culture in which the state was from then on, to play a major role.

The war was also to greatly politicise the African soldiers. What caused them to get politicised was the necessity for the colonial powers to provide a stake which would serve to mobilise them to war.

This had the effect, particularly in cases where outright concessions were made, to demonstrate to the colonised peoples that colonialism was not as invincible as they had previously thought.

Further, by causing the movement of Africans to distant places such as India, the war exposed the combatants to a range of experiences much broader and inspiring in the anti-colonial struggles than they had encountered at home. Those who served in India, for instance, got first hand experience of the double standards of Britain.

While being told that they were fighting to preserve freedom and democracy, in India, the combatants witnessed fellow colonial subjects being prevented from protesting British restriction on political freedom in India. Such experiences were to ignite a resolve in the combatants to wage struggles against colonialism when they returned home.

While this constituted the major immediate impetus to the evolution of countrywide nationalist movements in all other African colonies, this was not the case in Uganda.

In Uganda, these conditions, though favourable to mobilisation, instead fuelled two tendencies: the move towards Ganda separatism, and the evolution of an ambivalent nationalism.