Children live in fear of ritual sacrifice

What you need to know:

Every parent’s dream is to see their children live free of the known six killer diseases, including measles. But, ritual sacrifice is another sort of “disease” that many a Ugandan child fears could befall them anytime, anywhere.

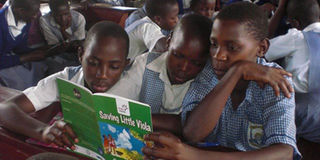

With their eyes glued to the storybooks on their desks that author Oscar Ranzo is reading aloud to them, it may appear that the primary six students at St Moses School, Jinja, are deeply immersed in an English lesson.

However the 70 pupils, aged between 10 and 13 years, are not concentrating on reading or writing skills in this class. What they are dealing with isn’t even on the national curriculum. But it may turn out to be as equally life-changing. As schools resume across Uganda, hundreds of students in Jinja, Mukono, Buikwe and Wakiso are participating in the Child Sacrifice Prevention Programme.

Last Wednesday’s workshop at St Moses marked the beginning of the programme, following a successful Unicef-funded trial last year in co-ordination with the charity Lively Minds.

“In Ugandan society, the belief in witchcraft is as big as the belief in Jesus,” says Ranzo, who will this year travel to hopefully at least 60 new schools reading Saving Little Viola, which he penned to highlight to students the dangers of child sacrifice and ritualistic murders.

“The book is supposed to make it easier for us to approach a very complex topic. Children are easier for us to target because we can go into schools and their mind-sets can be changed. It’s difficult to get access to parents and change their minds.”

According to figures from the police Anti-human Sacrifice and Trafficking Taskforce, the practice has been “steadily reducing” since 2009, when officers made a “deliberate effort to manage the crime”. There was one reported case of ritual murder in 2006; two in 2007; 16 in 2008; 15 in 2009; nine in 2010 and seven in 2011, the statistics show. “We’re on the right track to manage it, but it’s there,” says Moses Binoga, the outgoing head of the taskforce.

He says there are 14 cases from between 2006 and 2010 still being investigated; eight which have been put away as there are no leads, and 23 which have been committed to the high court. As most cases aren’t reported to the police, the real number is likely to be much higher and there has been some criticism of these statistics. But Binoga stresses there’s a difference between “guesswork” and “properly researched statistics”.

One high-profile case that found its way to court is that involving Kampala businessman Godfrey Kato Kajubi. Earlier this year it was reported that Kajubi was remanded at Masaka Central Prison.

He had previously been remanded late last year, days after his re-arrest for his alleged involvement in the ritual murder of 12-year-old Joseph Kasirye, in Masaka in October 2008. It’s alleged Kajubi hired witch doctors Umar Kateregga and his wife Mariam Nabukeera to slaughter Joseph for ritual purposes. The boy’s head was allegedly cut off.

Kajubi, who has businesses in Kampala, Jinja and Masaka, was originally arrested at a shrine in Lweza A Zone near Kajjansi, on Kampala’s outskirts.

In Saving Little Viola, a tale based on friendship, the story’s female protagonist fortunately doesn’t meet the same fate as Joseph. Sadly the story resonates all too well with the pupils of St Moses.

In 2010 the decapitated body of Aya, a 10-year-old pupil from the school, was discovered close to the nearby Nytil factory three days after being abducted. “A friend of the girl says she saw the mother of another girl pick up a hanky with chloroform on it and put it on Aya’s face before she was carried to a bedroom,” recalls teacher Sylvia Nabwire.

“She never saw her friend again.”

Three suspects, one female and two male, were let off due to lack of evidence, police say. More recently, five children from Kiryowa were nearly kidnapped.

“One was nearly grabbed by a man holding a panga,” Nabwire says. “But because of the workshop the kids were aware of child sacrifice and knew to run away. The programme has saved a number of children.”

After the workshops, students participate in poster-making competitions focusing on child sacrifice and other activities to “engage them”. Ranzo then revisits each school a month later, handing the children follow-up activities. When he began the workshops in 2011, he says more than 50 per cent of students across all 37 schools believed that child sacrifice could lead to wealth. Even more alarmingly, in some individual schools this figure was 80 per cent. Following the introduction of the workshops, this statistic dropped dramatically to 30 per cent across all schools.

“The programme actually works,” says the writer, who wrote Saving Little Viola several years ago because he felt child sacrifice wasn’t receiving enough media coverage in Uganda’s English newspapers.

Those that believe in the ritual practice do so mainly because they think that through it they can reap financial prosperity, or be cured of illness, Ranzo says. “It’s mainly locals, businesspeople, looking for money,” he says.

“People go to witch doctors before they go to the proper doctor.

“Sometimes people believe in villages that child sacrifice can cure diseases such as mental illness.”

Because of poverty it’s “very easy to lure children away with biscuits or sweets”.

Binoga says other reasons for consulting a witch doctor include wanting a “good fortune”, a desire to be promoted at work and wanting to find a husband or wife. Most of the victims are not in the care of their biological parents, but have been left with their grandparents or friends when they disappear, according to the police.

The ceremonies, which normally involve a child’s blood being drained and body parts cut off, are usually performed at night in buildings or homes, says Ranzo.

Different body parts are targeted depending on the client’s request. “(For instance) if they (the healer) cut off the breasts or cut off the private parts, that’s normally for child bearing or love potions,” Binoga explains. As their industry is not regulated, witch doctors, who charge up to Shw3m to perform a ceremony, are free to advertise on Uganda’s radio stations. But it’s also easy to find one simply through word of mouth.

Unicef is currently working with the Ministry of Gender and Lively Minds to see if the Child Sacrifice Prevention Programme can become part of the national curriculum. Meanwhile police are speaking on radio and TV and holding village meetings to warn parents about the practice. “There’s a need for the government to introduce a law regulating traditional healers,” Binoga says. There’s also a lack of proper understanding of the new law against human trafficking, The Trafficking in Persons Act (TIP) 2009.

The Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development in 2009 set up a joint taskforce with the Ministry of Internal Affairs to investigate the increasing cases of human trafficking and child sacrifices.

Ranzo has also written his next book, The White Herdsman, to educate children about the impact of oil production on their communities and how to deal with this.