Nyanzi fled country as a soldier, returned as an artist

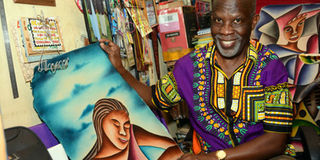

Art work. Nuwa Wamala Nyanzi shows off one of his art pieces. PHOTOS BY GODFREY LUGAAJU

What you need to know:

- In 1978, Nyanzi fled the country to Kenya, where he stayed with his auntie for some time before he linked up with a friend, Dan Sekanwagi, a freelance artist and they started making batiks as a means of survival. .

- Military. The year Nyanzi joined the military after the head of the military medical services in 1972 secured recruitment of Baganda boys.

From a medical family, into military service and to a self-taught artist of international acclaim. Nuwa Wamala Nyanzi, military number UA 17232, fled the country as a soldier, only to return as an artist.

Born in 1952 in a medical family, Nyanzi has no regrets that he didn’t walk in his parents’ footsteps. “My father was a laboratory technician and my mother a midwife nurse. This exposed me to lots of medical related practices from an early age,” he says.

During his school days, his class was either the last in an education system or the pioneer of a new one.

“The year I sat Primary Leaving Exams is when they introduced questions in Luganda and English, while my class was also the last in the junior two level.”

A year after joining a private secondary school in Mityana District in1967, Nyanzi sat for special exams to qualify for government sponsorship. “I passed the exams and joined St Francis Secondary School in Kampala, where I completed my O-Level. My first choice was Aga Khan Secondary School. However, Aga Khan SS did not admit students in Senior Five that year,” Nyanzi says.

Going to Nairobi

With the delayed admission, Nyanzi went to visit relatives in Nairobi, Kenya, where he trained in key punch operations. This was the precursor to computers. “I trained in how to put data on a card which would later be inserted into a huge machine (computer) the size of a whole room to be read.”

Nyanzi returned home in 1971 and went job-hunting.

“I had only one chance then, there was only one computer in the country at the national treasury. As I waited for an offer, an opportunity to join the army came and I could not let it pass by.”

The head of the military medical services in 1972 secured recruitment of Baganda boys.

“Dr Brig Bogere had been given 35 slots to fill in the army medical department. Among those he took included the late Prince David Joseph Ssuna, Maj Gen Kasirye Gwanga, Njuki, Jjingo, Lubowa a son of a former katikkiro (premier) Paulo Kavuma, Magembe, myself and others.”

The group was to do nine months of basic military training before going abroad for specialised training in different medical fields.

“After basic training, due to intrigue within the army, we were sent to Mbuya General Military Hospital to wait for a defence council decision.”

From Mbuya, the group started patronising night clubs like Suzana in Nakulabye. On one night, part of the group faced off with the State Research Bureau (SRB) agents over girls.

“We were at Suzana night club. I went to the restroom and on return, I found Prince Ssuna arguing with SRB guys. I got him out of the club, but the SRB agents followed us outside and we punched them hard, and left them licking their injuries.”

According to Nyanzi, the SRB agents accused Nyanzi’s group of taking their girls. “We had studied with these girls. The SRB guys wanted them but the girls preferred people they knew. Fortunately, neither they nor the SRB agents knew we were soldiers.”

Several incidents of this nature happened until Nyanzi and friends decided to abandon Suzana night club for their own safety. But that was not the end of clashes with security operatives over girls in night clubs.

“Another incident happened at Chez Johnson on Kimathi Avenue. I was seated at the terrace enjoying myself when my cousins came running from the dance floor shouting “batutwala” (they are taking us). Two guys were running after them, accusing the girls of abusing them. They wanted to take them away. I offered to deliver the girls to a place of their choice the next day but they refused. We went out where a scuffle ensured and a Special Branch officer intervened on behalf of the SRB. I gave him a karate kick, his pistol fell, and we took off.”

That incident was in the news the next morning and Nyanzi was accused of interfering with the state agencies making an arrest. An investigation was done and he was exonerated.

For art. Some of the picture cuttings of Nyanzi. Right is Nyanzi with a friend in the 1970s.

Despite being exonerated, another storm was brewing as Dr Bogere, who had seconded their recruitment, was accused of recruiting people with a plan to overthrow the government. The entire group was given 24 hours to leave Kampala.

“I was sent to Moroto, Kasirye Gwanga was sent to Moyo, Ssuna went to Bombo, Kavuma went to Kabamba, Jingo went to Fort Portal, we were scattered countrywide.”

Knowing the report sent ahead of him, Nyaniz expected hard life under Lt Col Ozo, who was the commanding officer of the Gonda Battalion. “Lt Col Ozo was a fierce looking man, but very kind. When I reported to him and explained what had happened, he just said “Hiyo ni fitina” (that’s jealousy).

Although he expected a tough life, Nyanzi ended up being deployed to work in the sergeants’ mess as a barman. “We called this light duty.”

Being a barman came with the luxury of accessing newspapers. “I made a collection of newspaper cuttings. When my boss found them, he thought I was good at information gathering and suggested I be transferred to intelligence.” This was a section of the army Nyanzi despised and he pleaded not to be transferred. “We despised intelligence people because they were never in uniform, yet I wanted the pride of putting on a military uniform.”

Nyanzi’s services at the Sergeants’ mess was cut short when it was discovered that he spoke fluent English. His commanders wanted him for a better post. When a message came from headquarters asking for two soldiers from Moroto to go for cadet training, Nyanzi and a one Changwa were selected.

“Unfortunately, on the eve of the departure date, another message came in, saying only one person was needed. We had to toss and I lost.”

In 1973, Nyanzi’s stay in Moroto ended when another message from Kampala asked for one soldier to be sent to Mbuya General Military Hospital. “On reporting at Mbuya, I was told they had no idea about my going there. But the deputy chief pharmacist asked me to stay around as they worked out my transfer papers.”

In the same year, Nyanzi started out as a medical stores trainee at the military hospital. By the time he deserted the army in 1977, he was an assistant store keeper.

Plot to burn Republic House (Bulange)

Following the failed coup of 1974, the suspected coup leader, Brig Charles Arube, was killed mysteriously, causing unrest among the soldiers.

We were very angry over Arube’s death not because he was a darling, but about the general situation.

The next day, soldiers were summoned to the general headquarters at Republic House for an address from president Amin.

As we assembled, information came through that Amin was with Lt Col Hussein Malera, the military police commander at the Malire base in Lubiri. This stirred more anger among the assembled soldiers.

Malera was one of the most hated commanders because of his mistreatment of others. We vowed that should he come with the president, we were going to burn down Republic House.

Amin may have been tipped off about the situation at the Republic House and he came alone. He used his charm to calm the tension.

We were all fired up, but as he reached the doorway, he was laughing and clapping, we all joined in, the tension in the hall eased.

In the hall, Amin immediately went on the attack, accusing the soldiers of harassing civilians who pay their salaries and buy them uniform. He said: “You waste fuel driving tanks around threatening civilians but they are the ones buying that fuel and paying your salaries. They are your masters, stop threatening and intimidating them. You have to respect them.”

At the end, he asked if we had questions. We were all silent.

A warrant officer II seated next to Nyanzi broke the silence when he stood up, saluted Amin and went on to ask why civilians were disappearing like needles. “People are disappearing, and your own escorts are responsible, they are putting people in car boots,” the officer said.

The packed audience clapped. I did not clap, fearing cameras focussing on me. Amin did not respond to it but he asked what we wanted and the soldiers replied: ‘we want Ali Toweli and Malera out of Kampala and your bodyguards should stop putting people in car boots.’

Within a week, Toweli and Malera were out of Kampala.”