Why providing storybooks at tender age sustains reading culture

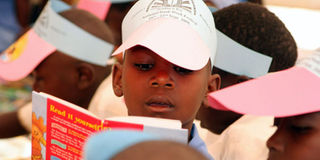

Pupils of Kasubi Primary School in Kampala in a reading class.

On a late afternoon on May 9, 2018, I find Marion Nabirye seated on a mat reading a storybook titled; When Hare Stole Ghost’s Drum written by Julius Ocwinyo (Fountain Publishers, 2005) at the Nambi Sseppuuya Community Resource Centre in Igombe Village, Buwenge Sub-county, Jinja District.

“I am reading this book because I want to know more English words to add to my vocabulary,” the 13-year-old tells me.

“I have been coming here since my Primary Four when I was at Omega Modern Day and Boarding Primary School in Buwenge. This centre has helped me develop my English construction and composition,” Nabirye, a Senior One student at Bupadhengo Secondary School in Buwenge, adds.

Benson Obeera, a Primary Seven pupil at Muguluka Primary School, is reading How Friends Became Enemies (Fountain Publishers, 2013).

“Our school library has textbooks that we read for only classwork. There aren’t any story books. I love stories because when they give us comprehension tests, I am able to answer them by first reading the passages,” the 16-year-old says.

Charity Mirembe, a 12-year-old pupil at St Maria Mulumba Primary School in Buwenge, is reading Lule The Lazy Boy written by Janet Mdoe.

The book is about a boy called Lule, who refused to bring a wooden spoon (omwiko) that his mother sent him for because he was lazy. Instead, the mother went to the house and brought the spoon and mingled millet bread.

Thereafter, Lule asked his mother to eat the remaining millet on the spoon. “You are good for nothing and you are the laziest person in this village,” the mother said in anger.

She then hit Lule with the spoon, which sent him flying in the air. His friends went looking for him in the air and did not find him.

“Through this story, I have learnt about the legends of our ancestors in Busoga. The main message in this story is that you should never be lazy, work hard and respect your parents,” Mirembe notes.

“It does not matter whether a book is large or small. What matters is if it has an interesting story,” 13-year-old Conrad Akesigaruhanga says.

“I like reading science fiction because it opens and widens your imagination. I also love adventure and investigative dramas such as Nancy Drew, Hardy Boys and The Famous Five Series,” Akesigaruhanga, a member of the Malaika Children’s Mobile Library, adds.

Ms Rosey Sembatya, the founder of the library, says Ugandan young children love reading colourful books.

Preference

“Once a book appeals to the eye, it is the first step to children wanting to look at it and open it. The Oscar Ranzo books are quite a catch, super heroes, princess stories, comics and Geronimo Stilton, among others. The folktales are poorly illustrated so we ask the parents to use them for storytelling since they lack the visual appeal,” Ms Sembatya says.

“Because we have made every reading academic, children prefer to read for pleasure. Reading for enjoyment; to read knowing that the choice to either answer the questions at the back of the page or choose not to is entirely up to them,” she adds.

Akesigaruhanga agrees with her, saying: “When you are reading in your leisure time, you don’t feel pressured like when you are reading for an exam. You don’t have to memorise everything like you have to pass an exam.”

“When you are reading for leisure, the books are interesting. Some are educative, some open your imagination, and some have different beginnings and endings, which tickles you to get ready for the next series,” she adds.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) based in the US defines literacy as “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, compute, and communicate using visual, audible, and digital materials across disciplines and in any context.”

“The ability to read, write, and communicate connects people to one another and empowers them to achieve things they never thought possible. Communication and connection are the basis of who we are and how we live together and interact with the world,” ILA adds.

Asked to describe the importance of the storybook, Mr Isa Maganda, a librarian at the Nambi Sseppuuya Community Resource Centre, replies: “I am looking at the storybook as something or material that can stimulate the interest or enthusiasm of understanding, discovering new ideas, knowledge in other displaces compared to textbooks.”

“Some of the books that we stocked had never been read by students in this locality because there was no interest or pressure. They don’t read for posterity, they read to pass examinations. This means there is no storybook in our national curriculum. That has hindered the interest of reading among our young generation. This means we are not going to have longtime readers,” Mr Maganda says.

“I have observed that people who picked up the reading culture in their young age are still reading in their adult age. They are more knowledgeable, they always have new ideas and increased life expectancy. They are never idle because they keep reading,” he adds.

Mr Yusuf Kyebambe, a teacher at Muguluka Primary School, observes: “The storybooks have improve the performance of our school because now the pupils read questions and understand. There are storybooks in our school library. We have changed the timetable to cater for reading activities either in the school library or classrooms.”

“Our biggest challenge in Uganda is that our school systems do not consider reading as a core foundation for a learner. So, they teach and allocate more time to academic subjects and they may give only one period to reading,” Ms Tinah Annet Wandera, a secondary school teacher and education consultant, says.

“On the contrary, reading can boost a learner’s word power, comprehension, concentration and expression, which can in turn improve their grades in all academic subjects. Reading is the surest way to ascertain that an individual will sustain life-long learning in future,” Ms Wandera adds.

She says a child is supposed to read one storybook each day in Primary Four and below but because schools give homework every day, it has replaced reading. “Government schools are comfortable because they are not required to provide storybooks. International schools provide storybooks to their learners every day,” she says.

“We have a poor reading culture in Uganda because children are busy with homework instead of reading at a tender age - the stage at which they are supposed to develop a reading culture,” the education consultant adds.

“Even then, children will not learn English because homework is majorly a salient activity as compared to storybooks that talk to you, transport you to other countries and cultures, take you through conflicts, feelings and other experiences. They expose you through visualising of people, images and places, as well as emotional feelings,” Ms Wandera says.

Homework burden

Akesigaruhanga’s grandfather, Yorokamu Abainenamar, decries the heavy load of homework that schools give children.

“As a result of the pumping of our children with lots of school work, they end up not having time to read for leisure. The end result is the suffocation of the reading culture and instead focus is only on reading for exams,” Mr Abainenamar says.

Ms Wandera says reading helps children develop the ability to concentrate, an aspect that is lacking in society today.

“People can’t concentrate in seminars and churches. These days, they tend to turn to their smart phones in public gatherings. We should invest in big demonstrative readers, where a teacher can dramatically read aloud to a bigger group to interest them into reading,” Ms Wandera says.

“A teacher reading aloud dramatically is the most effective way to interest children to read fiction. If there are NGOs funding motorised mobile libraries, they could have electronic books on computers and later donate the actual books to schools and children,” she adds.

Mr Elly Wairagala Musana, a curriculum specialist at the National Curriculum Development Centre, recognises the importance of a storybook in Uganda’s national curriculum.

“We use storybooks to enable learners to develop their reading skills. And readers have been developed for every class from Primary One to Seven. At least we are confident that in future, our citizens will be literate because the reading culture is being instilled right from Primary One.”

As to the value of the storybook to a child’s lifelong reading culture, Mr Wairagala says: “The storybook enables a child to integrate what he or she has learnt from the different subjects into his or her daily life. It also helps the learner develop various lifeskills, for instance, effective communication, creative thinking and problem solving.”

“The storybook should be examined in national exams to boost the reading culture in the country,” Mr Kyebambe suggests.

However, Ms Sembatya differs, saying: “Examining a book takes the fun out of it. It presents [it] like another chore. A storybook should follow the basics - be colourful, with a bigger font and be interesting. We go wrong by choosing the lesson of the story before the story itself. It turns out tight and boring. Just because a book is important to an adult does not mean that it will appeal to the child.”

But Wairagala defers, arguing: “Our examinations go beyond the classroom because some of the stories and poems that are tested are related to the stories the children read in the readers. Section A of the Primary Leaving Examination English Paper is done best by those children who have been reading for leisure. And we indeed encourage parents and schools to embrace the use of readers.”

“Our readers prepare learners to be able to write good compositions, conversations and hold debates, among others. So, a good teacher or school should not miss providing readers for the children. Remember that some values are better told through stories whether written or orally. We have encouraged schools to store children’s reading materials besides the prescribed ones. Today, we have a better conducive environment where reading for leisure is a priority. For example, newspapers have pullouts specifically designed for children,” Mr Wairagala adds.

Mr Maganda notes that the shortage of traditional folktale storybooks is a problem.

“The children usually ask for their local traditional folktales, which we lack in this centre. We have very few titles of Lusoga folktales. So we need more writers in this area to attract and maintain more readers here,” he says.

Folktales missing

“I tried to tap into the knowledge of our senior citizens in this area, who would come here and tell traditional folktales before the young ones. I would ask the young ones to listen, write and later translate with my help. We managed to publish a Lusoga folktale book titled Igi Lyomwandu (An Egg for Bride Price) under the African Storybook initiative in South Africa in 2015,” Mr Maganda adds.

He says the book has been translated into five local Ugandan languages.

As to the value of a library in developing a reading culture among the young children, Ms Sembataya observes: “The value of a library in this context is in its purpose of availing storybooks. To develop a reading culture, the books (read for enjoyment) must be made available and accessible. Accessibility means the child should be able to reach the books, and there should be deliberateness about the kind of books we avail. The library has to offer choice and abundance.”

Tomorrow, we look at policy challenges facing the provision of language and children’s literature in Uganda’s primary education cycle.