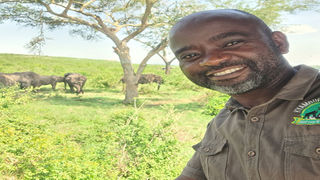

Aggrey Nshekanabo, the owner of Kyambura Safaris switched from formal employment into the hospitality business. In his early years worked as a waiter, kitchen runner, housekeeper and guide. PHOTO/Joan Salmon

|Prosper

Prime

From employee to entrepreneur

What you need to know:

While it is easier to transition to say, a grocery shop, the same may not be true for hospitality business. So, people keep one leg in formal employment and another in the hospitality business as they gain capacity.

After 10 years in the media industry and 13 years in the non-governmental organization world, Mr Aggrey Nshekanabo hung up the formal sector gloves to dig deep into the informal sector. This journey hinges on several times of his life.

The first one was at Nsere Lodge, the first private lodge in Bunyabiguru which also ran the Kyambura game reserve. Here, Mr Nshekanabo worked as a waiter, kitchen runner, housekeeper and guide.

“I worked there during my Primary Seven vacation in 1991 but they couldn’t employ an underage. They only took me on to support my education as I wanted to continue with school. Initially, I washed dishes as I learned on the job. When I turned 18, I became a waiter and due to my interest in geography, the guide job was added. I was also allowed to become a housekeeper,” he says. During that time, the seed of running a motel was planted.

The second time was during his time in the media, where he was drawn to writing tourism stories. That opened a door to travel to Simba Safari camp run by Mr Amos Wekesa of Great Lakes Safaris.

“All the rooms were taken up. Alongside Mr Ben Byarabaha of Red Pepper then and Amos, we used dormitory accommodation to learn from him. In addition, he invited me into the hospitality sector instead of being a spectator or critic,” Mr Nshekanabo said.

He had another Nshekanabo-Wekesa time in 2009 on a journey from Queen Elizabeth National Park through Kibaale. Spending 48 hours with Amos gave him the push to get into the hospitality industry.

While fully dipping his feet into the hospitality sector did not happen immediately, Mr Nshekanabo organised the travel of Mile 91, a filming agency to Uganda in 2010. In this instance, he did not feel the need to ask for payment though the client insisted on it.

“That was an eye-opener.”

That same year, he registered Kyambura Safaris, as a side hustle while working for the NGO. “I arranged people’s travels in and outside the country. In 2013, I became a travel logistics fixer for another film company from the US with partners in the UK for three years,” he says.

With the travel agency picking up beautifully, in 2019, it became clear that the side hustle and NGO work were conflicting. To focus on his travel business, he decided to transition. The other push was that the World Travel Organisation published a report saying 2020 was a year of travel and 1 billion people would travel across the world.

“My dream was to get only 100 of these travelers. With each traveller spending $2000 on their journey, I knew I would make a substantial profit,” he says.

Collaboration

Mr Nshekanabo collaborated with someone in the establishment of Naalya Motel. She previously worked as a manager of a top restaurant in Kampala and wanted to work in her restaurant. “The business is established at a property that a friend pointed us to hence starting the rehabilitation work in November 2019 with anticipation to open in December.”

However, this was delayed when suppliers delayed coming through and in March, Covid-19 shut down the economy. Nonetheless, in April 2020, they started selling food online as they had bills to pay. Finally, they opened their doors in June 2020.

Mr Nshekanabo says 90 percent of their clients are known to them. “I leveraged the NGO I worked at. It helps to build networks while in formal employment. It is these very people that dine with us or recommend clients our way,” he says.

Difficulties with the transition

Mr Nshekanabo is among the few people that have transitioned from formal to self-employment in the hospitality sector. While it is easier to transition to say, a grocery shop, the same may not be true for hospitality business. As such, people keep one leg in formal employment and another in the hospitality business as they gain capacity.

Ms Jean Byamugisha, the executive director of the Uganda Hotel and Lodging Owner’s Association (UHOA), says the assertion is true for several reasons:

Setup cost implications

Most hospitality facilities are built using loans. Ms Byamugisha says it is difficult to build a hotel from scratch out of their savings. Even if that were possible, starting the daily hotel operations becomes expensive without an extra income source.

“Getting a hotel facility that will assure one of profitable returns up and running needs billions in capital. That is why people get top-up loans to finish infrastructure development,” she says. Therefore, the transitioning into hospitality from formal employment happens slowly due to set-up costs.

Due to the nature of the hospitality business, one spends more at the beginning before seeing a profit. These include food and beverages, equipment purchases, salaries, and overhead costs.

“Having an extra income is crucial at the start because the hotel does not have committed clients hence no expected market so the hotel is not breaking even. That is why the salary comes in handy,” she says.

Seasonal business

In the hospitality sector, you will have a peak season and make abnormal profits. However, this will be quickly followed by a low season where you may not even get a client in a day.

“In the low season, expenses such as salaries, NSSF contributions, and utility bills must still be met hence the need for an extra income source to cushion them. This seasonal nature makes it impossible to fully transition into the hospitality sector before getting a grasp of the business,” she says.

There are overhead costs, just like any other business. However, the difference is in the amount one needs to cater for their hospitality business. First of all, the hospitality sector has about 25 taxes, many of which are replicated. These include a hotel licence, trading licence, swimming pool licence, bar licence, and tourism licence.

“Even when not operating at full capacity, you have to light up all the rooms, the garden lights. You also need to turn on the taps to avoid rust and flush the toilets so the system remains operational, not forgetting security. These are very heavy and cannot be sustained solely from hotel revenues, causing a delay in transition, especially at the start,” she says.

Ms Byamugisha says some people never transition at all, while some who choose to take the plunge and continue taking loans for sustainability. “The latter is not that profitable because it causes a strain on the hotel where costs may be passed on to the guests in form of high hotel fees. This is to pay up the loan and live off the investment,” she says adding that a gradual transition is ideal.

Furthermore, success stories start slowly. These may have a huge chunk of land by inheritance or purchase. They then set up a campsite and, after increasing popularity, may put up a restaurant. After that, five rooms are set up, to which they gradually add. There are also those with a huge house but are empty nesters hence slowly turning their home into a bed and breakfast facility. They expand gradually.”

Ms Byamugisha says this is the stress-free way of doing it for those still in employment hence not looking at it as a sole source of income. “It starts as a hobby or dream, gains momentum and becomes a retirement package. However, it takes time, even 20 to 30 years before it becomes a fully-fledged business,” she says.