A tale of Africa’s story in rich verse

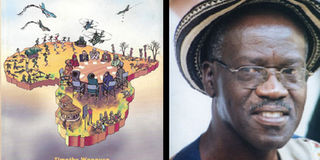

Timothy Wangusa, author of Africa’s New Brood and several other books. He is one of Uganda’s famous poets. NET PHOTO

Everyone should read Prof. Timothy Wangusa’s poem that gives his most recent collection of poems its title, Africa’s New Brood. But make sure while doing so, you are not taking tea because it will turn cold.

With its “sharp words”, you will forget the existence of the tea and your tongue’s exotic sympathies for it. After that one, read National Skulls Exhibition. Never again will you be alone in the night!

Creativity at work

Wangusa is able to create such effect because he is popular in the poetry literary circles and his name is easily recognisable. In fact Prof Gakwandi alleges that this new collection is the best Uganda has seen to date. While that may not necessarily be true, the 47 poems Wangusa shares are quite a delight.

The poems chosen, it seems, are from his writing of between 1985 and 2005 and the themes, or as they are classified: the modes, vary and paint a holistic picture of a poet in quest of appearing all universal in substance.

It is in truth not difficult to understand the poet and his expressions. Firstly, most of his poems are introspective in character, and, like playing tennis without a net, in free-verse form.

His style shows the liberty a poet posses to associate his interpretation of language with individual effervescent delivery is so vast that if not careful enough, whatever they possess the reader will disown, and it is a blemish even Wangusa is not above.

Criticism

The poem commemorating Makerere’s existence as a hilltop of the dawning day is one such. Free-verse finds its strength not in the quality of the writer but the reader’s and that is my worry here.

A reader groomed for literary critique will be so quick to point out the strengths, values and relevance of the poem, the one groomed for ‘literally critique’ will find it bubonic and even tasteless.

This apparent imbalance is not only restricted to such kinds of poetry. If anything, it is more prevalent in the metric-verse. But the challenge here is the poet gives us so little to look out for, or even to explore on the texture of style.

Good use of language

Secondly, diction being the magic wand he uses to ‘pierce,’ the internal rhyme also a purposeful trademark, he hardly varies the inscape and thus the monotonous sound he recurs in his works.

They end up sounding like a distant gong you come to anticipate every Sunday evening beckoning you for vespers. The language is rich and the imagery very provocative. The line from the poem When My thigh was a Book, “And all our writing dissolved in the night,/ Forcing our memory to become our thighs”, is one of the most poignant on the whole collection.

Recitation of western media

Thirdly, his poetry on African affairs, I feel, is a recitation of the western media portrayal of Africa’s image. The unwillingness to see beyond the challenges of the continent and problems of the nation singly announces the inferiority complex and self-disaffection we as Africans have more than readily exchanged within ourselves.

This is a very challenging perspective because as a poet, he commands a huge following of faithful readers. We must see beyond the mockery that laughs at us. Yet all that he writes about is indisputable. But it is how we respond to it and what we want to remember of the experiences.

If a poet became the biblical Amos, especially in an era where we need more than courage to look beyond our atrocities, we would all become the new-age brood beasts slouching to Bethlehem.