Prime

Mengo crisis: How Obote’s hands were tied over ‘Lost Counties’

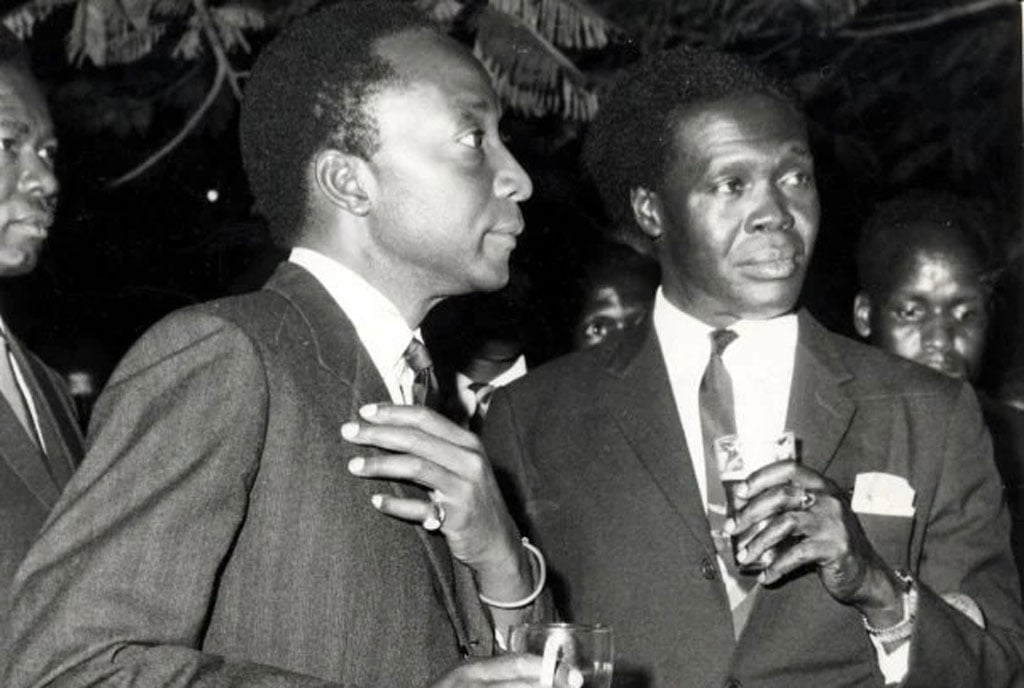

Kabaka Sir Edward Mutesa II and ex-Ugandan Prime Minister and also president Milton Obote. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- Book title: Reflections on the 1966 Political Crisis

- Author: Joseph Bossa

- Pages: 88

- Price: Shs20,000

- Where: Makerere University.

Former Uganda People’s Congress Vice President John Bossa, who passed away in 2019, wrote an intriguing book about the May 24, 1966, attack on the Lubiri Palace entitled “Reflections on the 1966 Political Crisis.”

The 1966 Mengo Crisis resulted from a conflict between Prime Minister Milton Obote and the Kabaka of Buganda, Sir Edward Mutesa II, culminating in a military assault upon the Lubiri, Mutesa’s palace that drove the latter into exile.

Bossa argues that the origins of this conflict arose out of Buganda and Bunyoro kingdoms’ disagreement over the fate of the so-called Lost Counties—Buyaga and Bugangaizi (or Bugangazzi, as it is known in Buganda). Buyaga and Bugangaizi had been annexed by Buganda in 1900 from the Kingdom of Bunyoro after the British had defeated Bunyoro Omukama (king) Kabarega in 1897.

Bunyoro had demanded the return of the “Lost Counties” before independence, but this did not occur. On August 25, 1964, however, Obote submitted a Bill in Parliament that called for the matter to be settled through a referendum.

The two counties were previously discussed at the two London independence conferences. The first of these conferences was held between September 18, 1961, and October 9, 1961, in Lancaster House. The second was held from June 13-30 in 1962 at Marlborough House. As a fudge or compromise, the British deferred the Lost Counties matter to a referendum to be held in 1964.

This was agreed to by both Buganda and Bunyoro. So Obote holding a referendum over the matter in 1964 was not in fulfilment of a personal wish, as Mutesa claimed, but of a constitutional requirement to decide whether the counties wanted to stay in Buganda, return to Bunyoro and stay neutral.

Bossa faults Mutesa for not appreciating this and he also reminds the reader that Mutesa set up the Ndaiga Development Scheme to entice Baganda, especially World War II ex-servicemen, to settle in the counties. These ex-servicemen would serve as a reserve force “when it came to a showdown”, as Mutesa wrote in his book “Desecration of my Kingdom.”

Obote foiled Mutesa’s plan by decreeing that only persons registered in the area for the 1962 elections could participate in the referendum.

The referendum was held on November 4, 1964, and the voters chose by a wide margin to return to Bunyoro.

Bossa presents Obote as a nationalist, holding the country together by taking into consideration not only Buganda’s but Bunyoro’s claims within the confines of the law. He also refutes the urban legend that Obote supported Mutesa becoming president of Uganda as a trap. According to Bossa, Obote went against his own party, the Uganda People’s Congress, in order to allay Buganda’s fears over its place in independent Buganda and the Kabaka’s position in the same.

Obote knew, better than most Ugandans, that Mutesa becoming president was a necessary trade-off to bring Buganda into an independent Uganda. Bossa supports much of Obote’s claims, especially the one where Obote claimed Mutesa had ordered Army Commander Brigadier Shaban Opolot to have him arrested in 1966. He also notes Obote’s restraint.

“All signs were pointing to increasing lawlessness, with intelligence reporting the stocking of arms in the Kabaka’s palace at Mengo and the convergence there of Baganda royalists, especially ex-servicemen in the Second World War,” Bossa writes, adding, “Obote decided to err on the side of caution by dispatching a team of Sixty Police Special Force on May 24, 1966, to check out intelligence reports of an arms pile in Lubiri.”

Obote’s advisors preferred sending in the army in the first place, but Obote demurred. Then the 60 Special Force personnel were “mowed down like grass”, thereby leaving Obote with little choice.

Bossa also presents Obote as a different person to the alleged person who seemingly hated Mutesa and thus sought to kill him.

He writes, “The statement by Prince Simbwa, Mutesa’s younger brother, who was in the place at the time, that he heard an army commander tell his charge not to shoot him (Simbwa) because they were under instructions not to shoot him (the Kabaka). Prince Simbwa bore a very striking resemblance to Mutesa and the commander must have mistaken him for Kabaka Mutesa himself.

This would give the lie to the allegations over the years that Obote’s orders were to capture or kill Mutesa.”

Bossa also reveals much of the hypocrisy of Mengo when it comes to how they treat leaders in the context of their interests. For example, when Mengo felt Obote was fighting for Buganda’s interests by having his party ally with the Kabaka’s movement, Kabaka Yekka (King Only), at independence, they baptised Obote “Bwete” and inducted him into the Mamba Clan (Lung Fish).

Even Idi Amin was initially feted by Buganda for overthrowing Obote and also returning Mutesa’s body for burial.

“Amin became the beneficiary of a whispering revelation that he was the secret son of Kabaka Daudi Chwa II, the father of Sir Edward Mutesa,” says Bossa.

As to whether, this crisis might have been averted if Obote never went ahead with the referendum. Bossa states: “Those who advance that view seem to ignore the fact that as far back as 1921 the Bunyoro-Mubende committee had been formed by Banyoro living in the Lost Counties to struggle for the return not only of those counties but also Buwekula, Singo, Buruli and Bugerere to the jurisdiction of Bunyoro from Buganda.”