Prime

At 55, there is still some fire power- Kabushenga

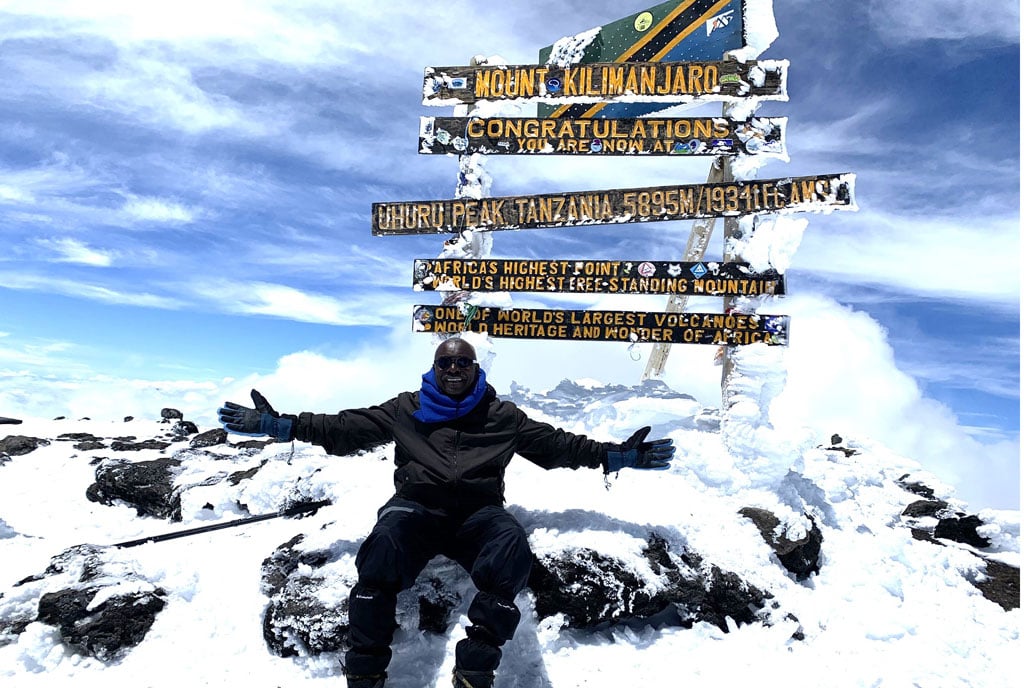

Robert Kabushenga conquers Uhuru- the highest peak in Africa. PHOTO/COURTESY

If you had told me in 1978, when the war to overthrow Idi Amin was raging, that I would make it to 55, I would not believe you. If you had told me, in the 1990s Aids scourge, that I would live this long, I would not have believed you.

The last time I celebrated my birthday was around 1993/94. At 55, according to World Health Organisation (WHO), I felt I had grown into an old man. And I needed to do something unusual.

So, I wanted to challenge myself in a way that would force me reflect on life than just merrymaking. I wanted something out of the ordinary. That is how the idea to climb Mt Kilimanjaro came up.

At first, I was unsure. When I shared this with my wife, I thought she, at the minimum, would say: “I do not think it is a good idea”. But she said “let us do this.” “And I am coming along.”

Frontline of death

At 55, I am at the frontline of death. My generation is beginning to die. This is the beginning of an end. I asked myself, how do I confront the end? What should the end look like?

There are things I do not play with, one of which is having the right logistical support for such adventures. You do not want your hiking experience to be messed up by poor planning and unprofessional guides. You want to succeed or fail because of yourself, not because of external factors.

So, I called Nkwanzi Travel. They specialise in mountain tourism. I have worked with them before and had a good experience. They have taken me to Mt Rwenzori and to Mt Elgon. I requested them to liaise with the Kilimanjaro guys and find out if it is possible to summit on November 22. I told them that the date was important. The Tanzanian counterparts told them it was possible. They got back to me with the costs. Just like that, I was now committed to myself, to my wife and to my travel agent. We had to get this done.

Preparations

Nkwanzi travel company had to coordinate with a travel company in Moshi to make the right bookings for accommodation (before and after the mountain), deciding which trail you will use, making sure we have a chef, securing guides, among other details.

We were told to get warm clothing, right shoes and pairs of trousers and jumpers. You can never ever be warm enough. You really must invest in warm clothing lest you become an ice block.

Costs

We got discounted rates from Uganda Airlines. We paid Shs6,001,248 ($1600) each, inclusive of accommodation and feeding. But people who intend to have a better hiking experience, I advise them to raise Shs7.5m ($2,000)

Thursday night

We landed in Moshi towards 9pm. We checked into the hotel and slept. Friday morning, we stayed at the hotel, getting briefed on what was going to happen on the first day. They checked our gear, ticking off everything. We had to get extra gear in form of duffle bags. I had carried the wrong shoes, so I had to get the right ones.

We spent that day packing. They inspect how you pack your gear in the duffle bags. You pack clothes for day one, day two and for day three [the last stop before reaching the summit]. But clothes for the summit day and your sleeping bag must be sealed in polythene bag (kaveera).

At the hotel, they measured our oxygen and pulse, every morning and evening. We were also started on anti-high-altitude medicine.

On the first day, I packed banana pancakes (kabalagala) and sugarcane. You will need these to boost your sugar levels.

When you eat three hardened pancakes with oats, your stomach just settles.

Day 1

We drive from the hotel to Marangu gate. They confirm our identities, make sure that the fees have been paid, they process our papers and we were shown our guides. Takes about an hour. Then we took a photograph at the gate.

We set off and head to the first camp,which is Mandara. You cannot hurry. You are not allowed to. It is a distance of about 6km, but it took us six hours. When the guide starts walking, it is like a wedding match. A very slow match, climbing through a rain forest, full of monkeys, greenery, clean waterfalls, nature at its best. You do not see the mountain.

You could go much faster and quicker, but the purpose is to get your body used to altitude gradually. The first day we reached the 2,000 metres mark and rested. We carried two litres of water and that is the minimum you must drink every day.

What am I doing here? The constant question is why? This journey forces you to introspect. Where is my life going? What actually matters in life? These are not thoughts you would ordinarily have. It is a time to reset.

Day two

It is a distance of 10km, a much longer walk through the moorland. It takes about 10-12 hours to climb. It takes you from the 2,000-metre mark up to the 3,700m.

The hiking team at Horombo camp on day two. PHOTO/COURTESY

The camp here is called Horombo. On the second camp, we took time off to train the bodies for the altitude. We took a walk to an altitude of 4,000 metres and came back to the camp.

Day three

We went through more moorland and entered an alpine desert. We had 10km to cover in about 12 hours, climbing, slowly gaining altitude, from 3,720m to 4,700m. At this point, I started to feel the pressure of going up, of thin air and the absolute cold. The third day ends at the third camp, Kibo.

We get to Kibo camp at around 5pm. It is freezing. We get together, get the final briefing and then had diner. By 7:20pm, we were in bed. At 10pm, we were woken up. You have been walking since 7:30am, you are tired, it is cold, you have just slept for three hours and you are woken up to hike on.

The final ascent

We unsealed our summit gear and dressed up. It is summit night. It is called the dawn attack. We have a meal, our gear is checked, and we are briefed. At 11:30pm, we start our hike. As soon as we step out, it starts snowing.

Do you know the most painful thing about that climb? You only have one option. To keep going no matter what. There is nothing you can do. You will never come back and say anything in Kampala if you do not reach the top.

A more experienced group by-passes us. We watch guys go up and up and and there seems to be no stopping. This is the greatest form of frustration. You are thinking, what did I get myself into? You cannot even go back because you do not remember the route.

You do not have the option of even sitting down. You give up, you die. It is a master class in focus, purpose and determination. Why are you there? What was your motivation? If you do not have a purpose, you will give up.

At some point, they put crampons as we started wading through the snow heading to the top. We meet people walking down and they tell us not to give up. That is the journey of life.

That you will meet people who have accomplished things and are willing to uplift you. But you will also meet others that will tell you, “Hiking is like going through hell.” And you start to wonder if you will ever make it.

Six hours later, about 5:30 am, we pierce through the clouds. And it is shining up here. But we are only just halfway. We reach at the first summit at 8:45am. Gilman’s point. How many kilometres have we covered? Four kilometres in almost 10 hours. We are at the 5,600-meter mark.

The summit

I will never, in my life, forget the moment I reached the point where I could see the signpost. On one side, there was a massive glacier. Winds are ripping through us and howling above us. It was biting cold. Then I saw the sign post. I broke down in tears.

It was a culmination of an effort. It is a reminder that the best things will require you to go through hell and back. But once you make it, the satisfaction is indescribable.

When you reach Uhuru summit, you will see two few pieces of wood and a Tanzanian flag. That is it. But you get here through grit. There are no shortcuts. You cannot fly here using a chopper. You must walk up here. One step at a time. It is painful. It is tasking. You cannot ride on someone’s back. You cannot bribe Uhuru peak to come down for you.

And for me it was even more worth it because at 55, there is a tendency is to think that you are finished, as you are beginning the aging process. You begin a decline and many accept that. For me, it was to say there is still some fire power.

When I got to the summit, I called one of the guides on radio call to find out if my wife was okay. He told me she was alright. They were three minutes away. When I saw her arriving at summit, I was excited to meet her. We matched to the summit together. A wedding match of sorts.

Walking down

Without the help of the porter, you are not going to come down. This is where humility comes in. You have to tell someone, “I fear going down”. You admit your fears to a stranger. And then he teaches you a way of coming down a hill and managing gravity and saving your knees.

Kabushenga (right) with Hilary Ndosi, one of the porters. PHOTO/COURTESY

It is an admission that despite all the things you have achieved and all the offices you have occupied, you will find yourself in a situation where you are going to depend on someone of a lower social status than you.

Do you have the humility to let this person know that they can be of help to you, even if you have lots of power, money and influence? In that moment, he is the only one that can help you out; not your money or power. All it takes is for you to acknowledge that he knows what he is doing.

Adapted from X (Twitter) spaces