Prime

‘There was no bush war promise to hand over power after 4 years’

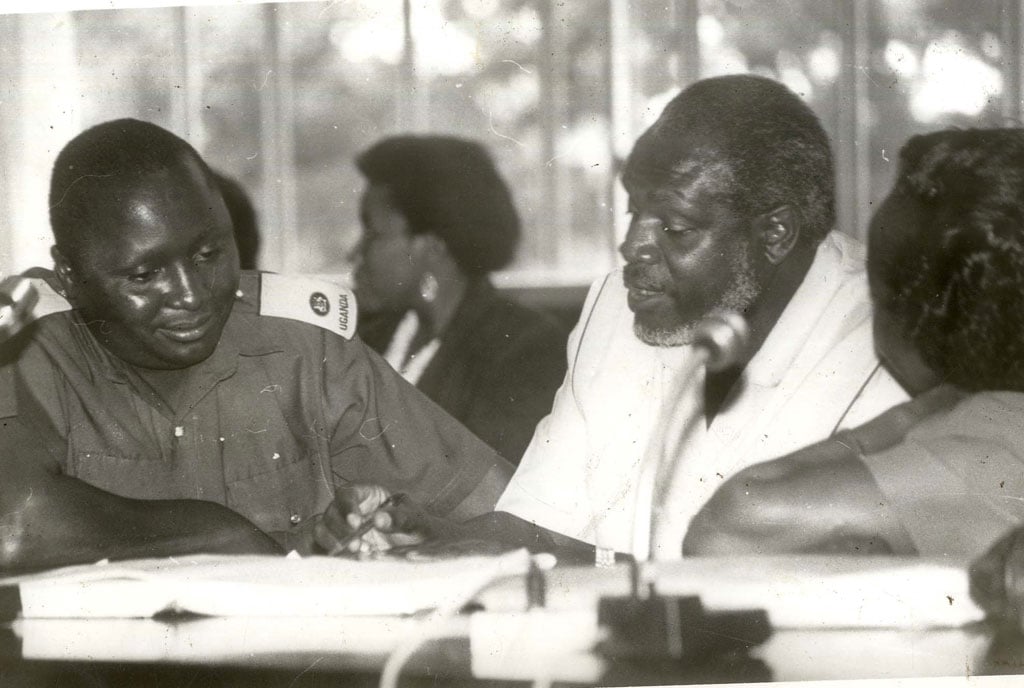

Left to right: Constituent Assembly delegates Maj Gyagenda Kibirango (NRA) and Jack Sabiiti (Rukiga). PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga’s comments were precipitated by the Budadiri East Constituent Assembly delegate, William Wanendeya, who had earlier accused the National Resistance Army (NRA) of reneging on a promise dating back to 1983.

Twenty-nine years ago, on Friday (May 24, 1995), Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga, a delegate of the National Resistance Army (NRA) in the Constituent Assembly (CA), revealed that the question of the National Resistance Movement (NRM) handing over power to an elected government after four years had never been discussed during the course of then Bush War that brought the NRM/A to power.

“Maybe it was another bush. The bush I know, where I was in Luweero, that issue of four years was never discussed. The issue came when we had captured power in Lubiri here. We said, ‘Okay, four years we think is okay’. But it was not a programme of the bush,” Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga said.

Friday Monitor of May 24, 1995, reported that the soldier’s comments were precipitated by the Budadiri East CA delegate, William Wanendeya, who had earlier accused the NRM of reneging on a promise dating back to 1983.

Wanendeya cited an unsigned anonymous 15-page letter that was circulating in top political circles at the time, which stated that guerrilla leader Yoweri Museveni had told a political seminar at Nshakazeragure, Lukoola, in 1983 that a victorious NRM would form “a transitional government of national unity for not more than four years, after which Ugandans should elect their leader”.

The document had reportedly been written and signed by disgruntled former NRA combatants.

The newspaper further reported that Wanendeya had also asked why the NRM/A had not handed over power to the Democratic Party (DP) once it had shot it way into Kampala.

“NRA went to the bush because elections were rigged. The logical thing that should have been done was to hand power to my brother [DP leader Paul Kawanga] Ssemogerere,” he said.

Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere. PHOTO/FILE

According to the newspaper, the question sparked off bouts of laughter in the CA.

At the time, delegates were discussing Article 85, which led to the creation of what we know as the Electoral Commission (EC).

The Article stated that, “There shall be an electoral commission which shall consist of a chairman, a deputy chairman and not less than three and not more than five other members appointed by the President with the approval of Parliament.”

During the debate, Mr Patrick Mwondha, who represented Bukooli County, sought to have the Article amended to empower political parties to have a say in the appointment of the EC. He argued that there was need to enshrine the spirit of consensus in the Constitution.

“The parties will give confidence and credence to the Electoral Commission...We are not asking too much for the President to consult with other contenders,” he said.

Mwondha sought to have the Article read that, “There shall be an electoral commission which shall consist of a chairman, with the political parties and with the approval of Parliament”.

The argument was, however, shot down by sections of the delegates, some of whom argued that if parties were to be consulted, it would only be proper that other interest groups like women, the youth and disabled be added to the list of those that the President had to consult.

The motion was defeated, but not before the proposal by the CA delegate for Maruzi County, Mr Adoko Nekyon, to fix the number of commissioners besides the chairperson and deputy chairperson at five.

Quick return to multiparty

Earlier the same week, on Tuesday, May 22, 1995, as the CA was getting set for the much-anticipated debate on a possible political transition, it emerged that minister Jaberi Bidandi Ssali and Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga had come up with a proposal that would have led to a quick return to a multiparty political dispensation.

The document proposed that the Movement type of administration, which restricted political party activity, would be brought to an end two years after the first election that would be held after the enactment of the new Constitution.

The first elections under the new Constitution came in 1996. It was the first direct election held under a no party dispensation.

By the time the two came up with the proposal, debate on Chapter 20 on transitional provisions was on the horizon.

Details

The duo’s proposal provided for, among others, a code of conduct for political parties.

It also provided for guidelines on the formation and registration of political parties, the nature and conduct of political and civic education, and the conduct of political campaigns.

The package, according to Mr Bidandi, would open up the country to competitive elections within five years of the first election.

“We are trying to set in motion a process that would bring consensus, but this is a preliminary position. It is sort of thinking aloud. We last November discussed in Committee Five proceedings on the issue. Some of them tried to sell closely related amendments without success,” Mr Bidandi said.

The CA’s Select Committee Five, which was dealing with Chapter 6 on the representation of the people and Chapter 20, had already made some decisions that would affect the political direction and history of Uganda.

Mr Obiga Kania had already sponsored an amendment to the effect that, “The people of Uganda shall have the right to adopt a political system of their own choice, through free and fair elections or referenda”.

Also within the same report were amendments that had been sponsored by another Cabinet minister, Mr John Patrick Amama Mbabazi, and one by Mr Kahinda Otafiire.

Mr Mbabazi’s amendment provided that the Obiga Kania amendment notwithstanding, the Movement system would remain in place for the next five years, effective the day the new Constitution would be promulgated.

Mr Otafiire’s amendment, which was co-sponsored by Mr Mwesigwa Rukutana, ensured that political parties would remain in abeyance for as long as the Movement political system was in force.

Select Committee Five had also decided that a referendum would be held in the fifth year to allow for Ugandans to make a decision on whether to retain in the Movement system or open the political space to allow for a return to a multiparty political dispensation.

Some of the delegates who were members of Select Committee Five made futile attempts at pointing out that the provisions and amendments were making the Movement a permanent political system.

Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga. PHOTO/FILE

Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga insisted that the Movement was a transitional arrangement.

“If the Movement continues, they should compete at par with the (other political) parties. You cannot keep the parties in the cold forever. You would be sending the wrong signals,” Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga told Monitor at the time.

At the time, what you know as Daily Monitor, with editions published on Saturday and Sunday, was a tri-weekly newspaper that was published on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

“At the end of the day politics does not lie in legislation. It lies in mobilisation and organisation. So, if the Movement organises better Bidandi and Serwanga propose that a two-year restriction of political party activities would be a reasonable period for the new Parliament to enact laws giving effect to the re-introduction of political pluralism,” Serwanga Lwanga argued.

As had been expected, the duo’s idea did not see the light of day.