What do 50 years of Uhuru jubilee mean to Ugandans?

Some of the entertainers who graced the Independence celebrations at Kololo last week. Photo by Faiswal Kasirye

What you need to know:

Food for thought. The government, with fanfare and splendour, commemorated the 50th anniversary of Uganda’s independence from British colonialism last week. Crowds gathered at the Independence Grounds at Kololo and else where to mark the day but after nightfall, all was done and the following day it was business as usual. But did Ugandans understand what the day meant to their lives?

Africa is obsessed with the golden figure of 50. Before Uganda, it was Ghana, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi and others. Next year, it will be Kenya’s time; and with a new president who would most likely want to bring the whole of Africa to Nairobi, we expect a good job.

With a history of violence, the 50th anniversary offered Ugandans another opportunity to pose and reflect on their past, and chart their future. And oh yes, have some fun.

But the biggest challenge for the jubilee festivities was to de-link it from the refractive political shenanigans obtaining in the country. And my personal opinion on this was to cast it as and in the broader context of the African liberation. It is only when we appreciate how Africa was colonised that we shall be able to appreciate the significance of national independence.

Colonialism

History reveals that the first power to establish a colony on the African soil was Phoenicia in 814 BC (and the last colonial power to leave Africa was Portugal in 1975 AD).

However, for academic precision, the last vestiges of colonialism (in all its forms) on the African continent ceased in 1994 when the people of South Africa exercised the principle of majority rule.

So, why does independence mean a lot in Africa? Is it the brutality of colonialism and casting of the black race as inferior? The resistance against this brutality gave birth to what historians call the African liberation movement.

In Zimbabwe, Ian Smith made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain in 1964 in a manner that the white settlers in the British colonies of North America gained independence from Britain. But Ian Smith was overwhelmed by the African liberation movement; he relented in 1980 and had to let go.

In South Africa, the minority white supremacists, deriving inspiration from the American experience, tried to hold out. But they too were overwhelmed by the Africans. They relented in 1994 (and let go).

The meaning of independence to Africa therefore is not only political expression but also a conscious (physical and psychological) expression of providential existentialism.

African independence made indigenous African groups avoid being a minority culture on their native continent unlike the so-called Red Indians of the two Americas and the Aborigines of Australia.

Independent Uganda

Uganda’s independence discourse can be divided into five major sections namely: 1) the struggle and achievement of independence; 2) the contest for supremacy by socio-political forces immediately after independence; 3) the civil wars between1981 and 1985; 4) the socio-economic stability and; 5) the challenge of transition the country faces now.

Like most African countries, Uganda has had its fair share of challenges in the struggle of nationhood and State management. The sense of hope, purpose and promise in October 1962 was lost within the five years of independence.

The purposefulness and promise was the aggregate result of a united national struggle against a regime that was clearly an occupation force. Whereas all the socio-political formations were united in the nation’s struggle for independence, these forces turned against each other within five years.

This immediate post-independence struggle was, however, not that of nation building but a selfish struggle for exercising supremacy on the part of protagonists.

And within nine years of independence, the struggle for supremacy had left all the socio-political forces so weary and weakened that the military found it easy to intervene in January 1971.

The significance of the 1971 military coup is that it created another political constituency: the army. This complicated matters because of the army’s nature and special possession of instruments of coercion. Needless to say, from 1971 to date, the army has become such a big player in the civil and political management of the affairs of the State.

In fact from 1971 to date, governments in Uganda have either been military or a coalition of military and civilian rulers. The army is actually the only ‘political’ constituency with the widest latitude and leverage to influence political outcomes from any civil and civic processes.

Golden Jubilee

Now, it is not lost on us that anniversaries, by their nature, engender a universal sense of celebration. Remember the messianic Y2K madness of January 1, 2000?

However, in spite of human segmentation of time in weeks, months and years, the contiguous nature of time remains a reality like the continuous struggle for the betterment of humanity.

Before October 9, 1962, the British negotiated their departure with four principal partners namely the former kingdoms of Buganda, Bunyoro, Tooro, Ankole (and the Busoga Territory and the rest of Uganda).

All these socio-political forces were held as the trustees for the purposefulness and promise that Ugandans always associate with independence and the so-called “good old times”.

Fifty years later, where are these principles? And what role have they been assigned in the struggle for social progression? It’s a fact that every attempt to ignore these social-political issues has not helped in the country’s struggle for social progression.

The NRM

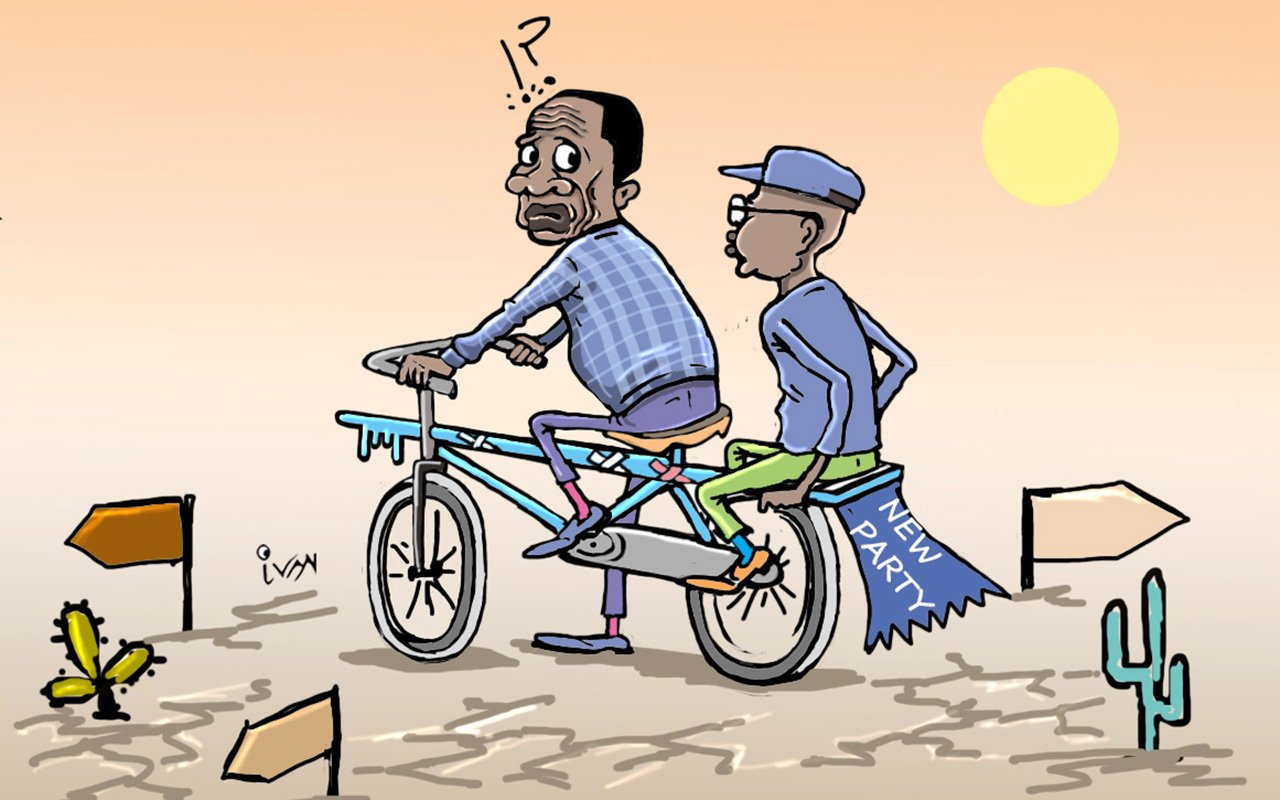

In spite of passing through 26 years of relative calm, the country seems to be at crossroads (again); like a lady in midlife crisis. Like it was immediately after independence, the socio-political forces are challenging each other. It is now difficult to determine how this challenge will end.

It is becoming clearer that the country is likely not to have a smooth and peaceful transition of power without the influence of the military. In spite of all else, the country seems to be reaching a point where a military takeover would not be a ‘scandalous’ proposition.

For 26 years, President Museveni has done everything (good or otherwise): from ruling for such a long time (against a background of short lived regimes), to appointing his wife minister, his son’s service in the military, relative calm in the country, holding more than four consecutive elections, an exponential population growth, economic growth etc.

In all honesty, President Museveni seems to have exhausted all he can do for Ugandans, save for one thing: handing over power peacefully. This is made even more poignant because of the creeping sense of civic and popular helplessness that more often breeds violent agitation.

Anecdote

In spite of my denigration, I must confess that I personally attended the very first initial meetings that prepared the Golden Jubilee Commemoration of Independence. It was in 2010.

Mischief being my middle name, I remember suggesting (in one of the meetings) that “since we are going to have elections in 2011, we should not mould the presidency and Office of the President on the person and personality of President Yoweri Museveni”.

With the shocked eyes fixed on me, I was bailed out by someone (who shall remain anonymous) who burst into laughter and dismissed me and my suggestion as a bad joke. We continued with the meeting.

In another meeting, we resolved that a team be sent to Ghana to acquaint itself with the experience of organising and managing a similar event. Ghana had celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2006. And please don’t develop ideas about me because I say ‘we’; I was just a fly on the wall.

‘We’ later found out that the management of Ghana’s Golden Jubilee Commemoration of independence was a Kampala-Chogmish affair.

The government that organised the 50th commemoration was voted out of power in 2008 and the new government asked for accountability for the event.

In an inexplicable way, the records for the expenditure of Ghana’s Golden Jubilee Commemoration were burnt in an alleged act of arson.

‘We’ were left with Malaysia (which had also held such an event).

By the time ‘our team’ went to Malaysia (I am really not sure whether the Malaysia trip happened), I had ‘revoked’ my fly-on-the-wall status and retired to my old digs in Kasese where I took refuge from the rat race.

The author is the Executive Editor, East Africa Flagpost.