Prime

Challenges in ending hospital detentions

What you need to know:

- In some health units where user charges are in place, exemption mechanisms have been introduced.

- Patients to benefit from such exemptions are given exemption documents or may be assessed by the health workers to determine the ability of the patient to pay.

There have been global efforts to end the practice of detaining patients in health facilities for failure to pay their health bills. Many of these efforts have been focused on the development of international human rights laws and national legislations. However these measures have not been effective in stopping the practice.

It is apparent that some health workers are not aware of these laws and their legal obligations. They do not seem to know that hospital detentions are illegal.

Detained patients are also not aware of their rights and even if they are, these patients face barriers to making complaints or seeking legal redress. The patients also have limited access to health complaints mechanisms. Seeking legal redress is often expensive financially and may take a very long time.

In many jurisdictions health services have been decentralized and are therefore the responsibility of the local governments. In these decentralized systems policies and legislation made at the national level may not be easily practiced. It is even more challenging when some of the health services have been privatized. Cooperation among the various government agencies is sometimes inadequate in decentralized systems.

Detention of patients is noted to occur mainly in health systems that have a poor health financing system. This occurs in low and middle-income countries. In these countries the overall level of public funding for health units is low or non-existent.

Even when there is some sort of funding from the central government the releases are late. There is often a general disconnect between the releases and the needs of the health units. In these countries health insurance schemes have not been put in place to address some of the challenges of health financing.

Many health units in the low- and middle-income countries rely on direct out-of-pocket payments as a source of revenue. These are often the only funds over which hospitals have some control over, which funds they use as operational funds or to provide bonuses for health workers. Health workers may, as a result, have a direct interest in increasing the collection of these monies.

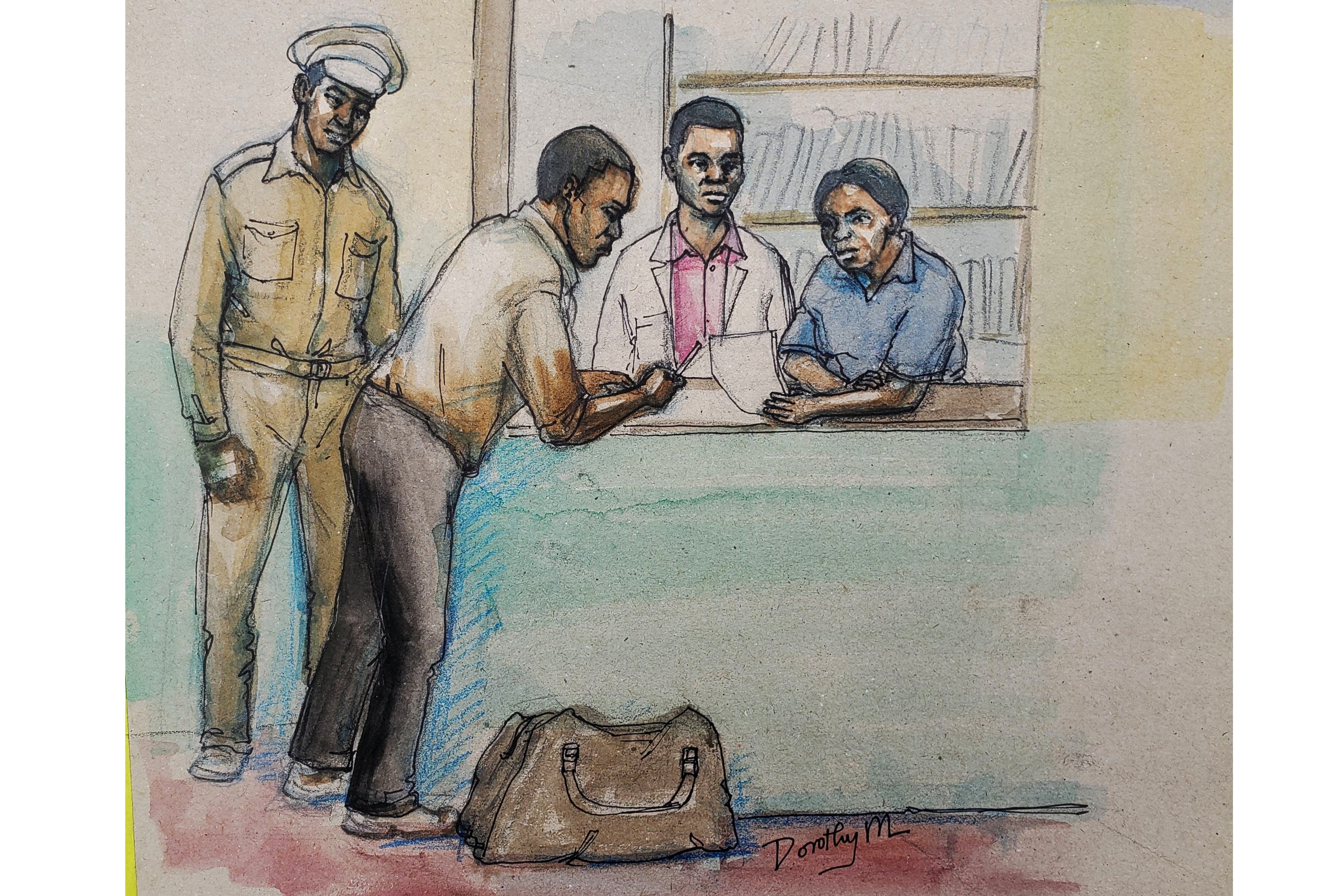

Hospital detentions often affect the most vulnerable in the society as these people cannot pay for or have some form of health insurance. In some health units where user charges are in place, exemption mechanisms have been introduced.

Patients to benefit from such exemptions are given exemption documents or may be assessed by the health workers to determine the ability of the patient to pay. However, these forms of exemption based on direct targeting often do not work and this may be because the policy and guidelines on who is eligible may not be clear. Inadequate identification of beneficiaries can lead to patients falling through the safety net.

In many countries there are no laws explicitly prohibiting the detention of patients for financial reasons. Where such laws are enacted the definition of the term “hospital detention for financial reasons” should be defined, including the circumstances.

Such laws should clearly distinguish circumstances where detention in a hospital may be justified for public health reasons such as to prevent the spread of contagious diseases.

The laws should be enforceable and provide causes of action for patients who are detained and should provide for court-ordered release of patients or the release of the bodies of deceased patients.

The laws should also provide for actions such as fines against the culprits as a deterrent to the practice of hospital detention.

The laws should also provide a provision that prohibits health facilities and health workers from refusing to treat patients, on financial grounds, in case of medical emergency.

Many countries that have ratified the international conventions and laws on human rights have not domesticated these laws and there are no provisions in the national constitutions incorporating these conventions and laws. The minimum health services that citizens are entitled to must be defined by law; it is not enough to leave it in the vague form of “the right to health”.

A domestic law should be established to formalize access to a package of essential health services. One of the provisions of the Sustainable Development Goals, which recognizes the rule of law as essential for development, is to promote the rule of law at national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all.

The SDGs calls for non-discriminatory laws and policies including those applicable to and in the health sector.

Contracts between health insurance and health service providers may go a long way in minimizing detention of patients for failure to pay for health services.

Health units that are aware that they may lose their practicing licenses will minimize on the practice of illegally detaining patients. This is one way of holding such health units accountable.

A law is not useful if it cannot be implemented and enforced. This calls for the need of well-resourced institutions to monitor ongoing compliance and to take effective action to enforce the law should this be required.

There should also be impartial dispute resolution bodies and processes for patients to help to enforce patient rights. All stakeholders, including social workers and local authorities, need to be aware of and know the legal situation regarding hospital detentions.

Hospital Management Committees, local politicians, Members of Parliament are all stakeholders and should hold the health care providers accountable and provide an oversight role and collaborate with each other.

To be continued

Hospital detentions often affect the most vulnerable in the society...

Dr Sylvester Onzivua

Medicine, Law & You