Church targets youth in fight against alcohol, drug abuse

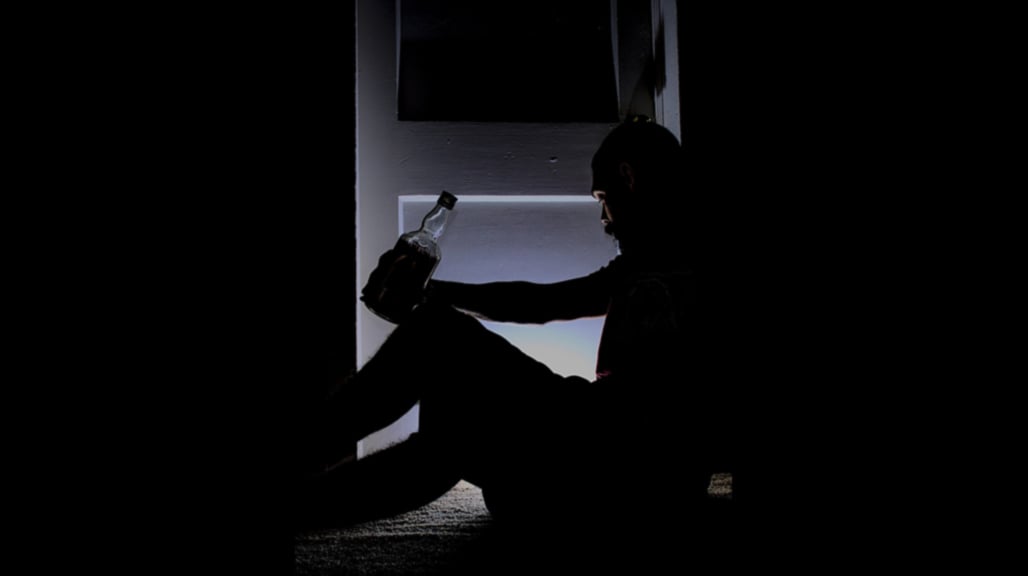

A picture of a man drinking alcohol. Many youth in northern Uganda have turned to drugs and alcohol due to unemployment and depression caused by the long term effects of the LRA war. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- Trend. A report by Makerere University School of Psychology in February 2021 shows that the level of drug and substance use was highest in northern region followed by western region, South-western and central regions. The report shows that about 60 per cent of students in primary and secondary schools drink alcohol and more than a third have consumed marijuana, cocaine, and other prohibited drugs.

Mr Dan Olinga was 26 when he left Erute Internally Displaced People’s (IDP) Camp in Lira Town to resettle in his village in Apiioguru, Alito Sub-county in Kole District in 2005.

This was after the war against the Lord’s Resistance Army rebels subsided.

Without finances, food, and other resources to start a new life, Mr Olinga soon resorted to alcoholism and substance abuse such as marijuana, hoping to relieve his stress and frustration.

Besides losing his physical stature, Mr Olinga dropped out of a vocational school where he had enrolled for skills training with the support of a local organisation.

Since then, he has been to prison twice for assaulting an elderly man and theft of a goat, for which he served a combined four years between 2014 and 2018.

Without anything from which to earn a living, Mr Olinga on a daily basis consumes ‘dete’, a local gin brewed from molasses.

Last week, he was among the 35 community members who got a psychological orientation and detoxification treatment at Alito Catholic Parish.

For the past two months, Mr Olinga was living on the streets of Lira Town after being banished by family who accused him of stealing household properties and wasting their assets.

“I was told to return home on condition that I have abandoned alcohol and drug abuse, that is how my younger brother collected me from Lira to come for this treatment,” he said.

“I want to be healed and get my life rebuilt again, I have done many things I should never have done because I am always aggressive and destructive under the influence of alcohol. I am sure at my age I can still regain my productivity once I recover,” he added.

Last month, two Catholic priests in Lira Diocese embarked on fighting alcoholism and drug abuse in Lango Sub-region through psychosocial support and treatment of severe cases.

In an interview, Rev Fr Emmanuel Okodi, the head of Alito Parish, said he partnered with Rev Fr Ponsiano Okalo, a senior psychologist and lecturer at Lira University, to start the classes and treatment sessions in Kole District.

“We interact with the community daily and the burden of alcoholism and substance abuse is so big not only in Kole but also throughout Lango. We believe that by changing the life of a community member, the community changes and progresses,” Fr Okodi said.

In Alito Sub-county, for example, Fr Okodi says since the LRA war ended, little effort has been put in place to psychologically restore the lives of the local people, forcing them to resort to drinking as a form of temporary relief.

“In my parish (Alito Catholic Parish) that has 45 chapels with an estimated 24,000 people, at least 10,000 (adults) are exposed to abuse of alcohol and other substances due to the presence of many brewing joints,” he said.

Treatment gaps

During the sessions held twice a month, the affected people are counselled before they are medically examined for alcohol and substance levels in their blood.

Alcohol-related diseases, especially sexually transmitted infections, mental disorders and traumatic experiences remain a common occurrence in the community and once an action is not taken, the future and quality of the population is at stake, Fr Okalo said.

“Due to the high prevalence of poverty and illiteracy, more people in our communities are battling with alcohol and drug abuse during this Covid-19 pandemic,” Fr Okalo added.

The priest’s statistics are backed by a new report by Makerere University School of Psychology, which in February 2021 revealed that the level of drug and substance use was highest in northern region followed by western region, South-western and central regions.

The report shows that about 60 per cent of students in primary and secondary schools drink alcohol and more than a third have consumed marijuana, cocaine, and other prohibited drugs and substances.

With a population of about 43 million people, registered rehabilitation centres of drug addicts in the country are few. For instance in northern Uganda, there is only PACTA Recovery Home. Others operate secretly to avoid paying taxes.

All these treatment facilities are private and inaccessible for most poverty-stricken people in need of treatment. Instead, they must depend on the country’s single, overcrowded Butabika mental hospital in Kampala which can only admit extreme cases.

Efforts

The use of narcotics in Uganda carries a penalty of Shs3 million or a prison sentence of five to 25 years. Critics argue such strict laws prevent people from seeking help.

At PACTA Gulu, a Catholic-run rehabilitation and treatment centre, a client has to part with Shs30,000 per day to access treatment.

Each patient is issued a private room with regular meals. Clinical staff put patients on a detoxification programme on admission and monitor for symptoms of withdrawal. They assess whether to discharge patients after nearly two months or offer further treatment.

Rev Fr Samuel Mwaka Okidi, the center’s founder and director, says ignorance and poverty have continued to limit many victims of alcoholism and other substance abuse from accessing treatment.

Because of poverty and ignorance, Fr Mwaka says that there is still a fraction of the community who take their addicted children to witchdoctors, mistaking the symptoms for witchcraft.

“Currently we have 12 clients at the centre with a total capacity of 20. The biggest challenge we face in the region is denial and resistance by those who have the problem. When they find themselves at police or prison upon committing offences is when they begin to feel the need upon release,” he says.

According to Fr Mwaka, many people who come to the centre are forced by their relatives.

“The victims don’t admit they have problems, others are brought by relatives by force and after a week or two, and it is when they begin to realise they have problems,” he says.

“The average people here in the region have financial difficulty to access treatment, which contains physical, psychological, spiritual, contents.

We ask for Shs30,000 per day, about 10 per dent of what is required to help a client in a day,” he adds.