Prime

Eastern, Northern regions top in poverty - WB report

The report, World Bank said, was based on data from three rounds of Uganda National Household Survey, three rounds of Uganda Panel Survey, seven rounds of Uganda High-Frequency Phone Survey, Uganda Refugee High-Frequency Phone Survey and AfroBarometer data.

What you need to know:

- The report, World Bank said, was based on data from three rounds of Uganda National Household Survey, three rounds of Uganda Panel Survey, seven rounds of Uganda High-Frequency Phone Survey, Uganda Refugee High-Frequency Phone Survey and AfroBarometer data.

- Ms Mukami Kariuki, the World Bank’s Country Manager in Uganda, said up to 50 percent of the population is vulnerable to the above shocks and they can fall “into poverty in next two years.”

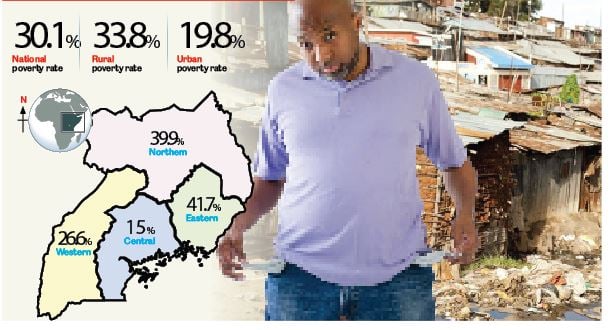

A report released yesterday by the World Bank indicates that poverty rates are highest in eastern and northern regions at 42 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

The report shows that these rates substantially varied from those of the western region (27 percent) and central (15 percent), and were also above the national average rate of 30 percent.

Although some regions are doing better than others, all the areas still fall short of the government’s target of reducing the poverty rate to 14 percent by 2020. This raises questions about the effectiveness of past interventions where the government spent billions of shillings.

Economists at World Bank attributed high levels of poverty in the eastern and northern regions to limited access to infrastructures such as electricity, erratic rainfall (drought), low levels of education and small markets.

The report, World Bank said, was based on data from three rounds of Uganda National Household Survey, three rounds of Uganda Panel Survey, seven rounds of Uganda High-Frequency Phone Survey, Uganda Refugee High-Frequency Phone Survey and AfroBarometer data.

The report details poverty trends in the country from the 2012/2013 financial year to 2019/2020 when there was a Covid-19 outbreak. It shows that national poverty rates have been fluctuating from 31 percent in 2012/2013 to 32 percent in 2016/2017 before declining to 30 percent in 2019/2020.

Speaking during the report launch, Mr Aziz Atamanov, the World Bank senior economist, said they discovered that during the last decade, Ugandans were hit by multiple shocks, including weather shocks (drought), Covid-19, Ebola and the war in Ukraine.

“When we look at the incidence of the shocks, we find that the poorest in rural areas are the most affected because they don’t have savings and they had to use detrimental coping strategies such as reduced consumption of food,” Mr Atamanov said.

The economists also said the results were not appealing when they looked at how the country is adjusting to coping with these multiple shocks.

“We found out that although non-farm jobs are growing, they are not readily accessible to the poorest who need the jobs the most,” Mr Atamanov said.

The economists at World Bank also looked at agriculture, which employs the majority of the population. “We found that it is very much dependent on weather and there is no fundamental change in the production process. This means every future shock can increase poverty,” Mr Atamanov warned.

Vulnerable population

Ms Mukami Kariuki, the World Bank’s Country Manager in Uganda, said up to 50 percent of the population is vulnerable to the above shocks and they can fall “into poverty in next two years.”

Dr Michael Atingi-Ego, the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Uganda, who was at the launch, said the country should focus on financial inclusion to reduce vulnerability to shocks.

He said: “We need to expand financial service delivery channels to rural areas, promoting the uptake of digital financial services and increasing formal financial account ownership,” he said.

The Deputy Governor said the government should also focus on adopting modern methods of agriculture such as irrigation to improve production, processing, value addition and exports.

Sub -regions also had stark differences in poverty rates; the Kampala sub-region had the lowest poverty rate of just four percent, which was 20 times lower than that of the Karamoja sub-region (70 percent) and Acholi subregion (72 percent), the report indicates.

Determinants

“In contrast, the combination of high population density, better access to infrastructure and markets, and higher human capital indices seem to contribute to subregional economic development, measured by night-time light (NTL),” the authors wrote.

Mr Atamanov recommended that since agriculture is associated with low growth potential, the government should find ways to move people to service-based jobs in urban areas.

He, however, said this doesn’t mean everyone should move away from agriculture as those who can adopt (expensive) modern methods of farming can continue in this business.

However, Ms Sheila Kawamara-Mishambi, the executive director of the Eastern African Sub-Regional Support Initiative for the Advancement of Women, said Ugandans have a competitive advantage in agriculture. She said the government should invest more in agriculture to increase productivity and value addition.

Ms Kawamara also questioned the use of level of consumption as one of the measures of poverty, saying it doesn’t paint a clear picture because some people spend less because they are saving and not because they are poor.

She also questioned the World Bank data on savings, saying many Ugandans save in terms of goats and cows they keep and do not necessarily take their money to bank.