Prime

Don’t cry for us Uganda, we never left you

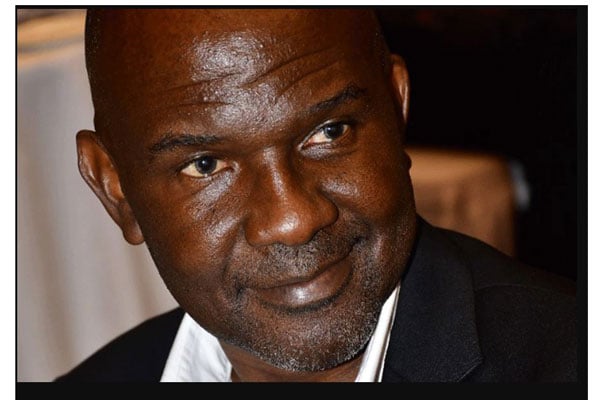

Mr Charles Onyango-Obbo

What you need to know:

- The men who hacked through the hills to build rocks that built this country made their beds in camps beside the road.

On the 61st anniversary of Uganda’s independence, we travel 50 years back. I was a kid still struggling to clean my nose when, with the family, I made my first journey from the far east of Uganda to the near-far west. This was still Uganda of the “old days”. It was a time when Radio Uganda played music by jazz greats like Louis Armstrong, and Harry Belafonte, and we were expected to appreciate it (we did).

It was a strange country for me and my siblings, but not so for our parents. They were the second generation to experience Uganda as something bigger than their clan, ethnic group, or district. Our mother used to talk about going to school in Nsube, Nkokonjeru. Our father, now there was a character. He was a college teacher in his early days, before becoming an education bureaucrat.

He was a polymath, accomplished in Maths, Science, English, History, Geography, and sports (being a notably autocratic coach who got results). He was also a polyglot. Apart from English and Kiswahili, he spoke seven other Ugandan languages. If he had been born in later years in a different context, he might have been the stuff of greater legend.

He and a group of friends like long-term Inspector of Schools Tom Mugoya were men of their age. They had been childhood friends and remained so until their deaths. They spoke of studying as far away as Mbarara. For me, Mbarara could well have been Greenland. We ended up outside Fort Portal, which was to be our home for nearly 10 years. It was a polite, pristine, Christian community. But unlike our parents who had been all over the country, it hadn’t had much contact with outsiders except American Catholic missionaries.

We were the first family to live in the area whose names started with “O”. Not surprisingly, they called us “badudugu”. I didn’t see anything outward about it, the way my older and more conscious brothers did. Though the sense of being an outsider was inevitable, they still made enough room for us to thrive. At St. Augustine’s College where our father worked, for the first time, I encountered “refugees”.

No matter how much they told me about Rwanda and how the slaughter there made them refugees in Uganda, I didn’t get it. It would take years. But being outsiders too, we formed a bond which remains to this day. Some of the little ones grew up, went on to fight the Rwanda Patriotic Army/Front return-to-the-motherland war, and became big men in Kigali. At a nearby trading centre, the traders were Asians. They were part of the wider outsiders’ circle. Then we got to meet (South) Sudanese refugees and the Nubian community.

As our minds opened up further, I became alive to the fact of internal migrant labour. In the area, there were Bakiga migrant labourers; famously hard-working, and cheap to hire. There was no way of understanding the climate and population dynamics that had driven them from Kigezi at the time, and why they lived on the fringes of local society. The snobbish Tooro elite in the area, nose up, treated them with thinly disguised contempt. One of them, Patrisi, became our hero and image of the hard-working Ugandan man.

Yet in those confusing times, the one thing that truly impressed me wasn’t the society. It was the roads cutting through or built on hillsides. I always asked how they had been able to cut through the hills and move the big rocks out of the way. Our parents didn’t explain the technical details, only telling us it was the work of the Italians. They did it with tractors, and the local people finished the jobs with pick axes. I grew up thinking very highly of the Italians (and Catholic missionaries). There is still a lingering admiration of Italian handiwork inside me.

There were also many “PIDA camps” (we learnt only later that PIDA was a local adaption of Public Works Department, PWD) along the roads in Uganda. Many towns today have grown from these PIDA camps, but I have never been able to reconcile to their disappearance.

Later, as we left Kampala to go into Mubende, for the first time we encountered roadblocks. We’d never seen roadblocks before. Our parents explained that it was because “Buganda was under a state of emergency”. It made no sense. We didn’t realise then how much the gun had begun to shape Uganda.

In adulthood, I came to understand that those were just some of the foundations of this land. There were men and women in this country who spoke seven to 12 Ugandan languages fluently. Uganda always had a generous spirit, embracing those from afar fleeing adversity. The men who hacked through the hills to build rocks that built this country made their beds in camps beside the road. The gunmen have bled it, yes, but that greatness still beats in its heart. Happy 61st UG.

Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. Twitter@cobbo3