Prime

We turned schools into profit centres, we can’t now turn them into charities

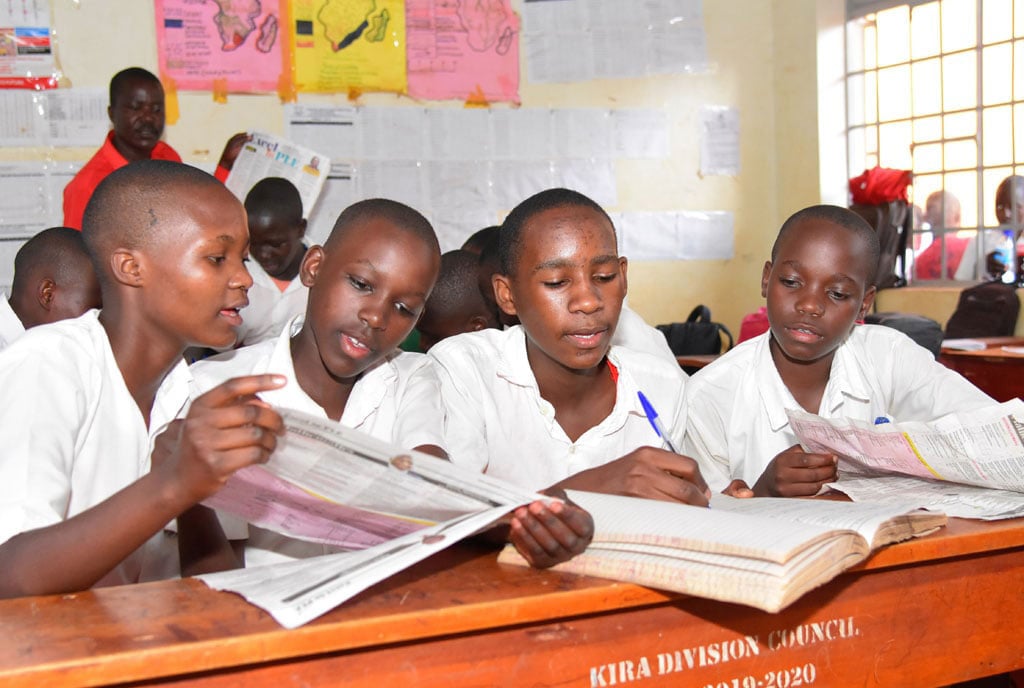

Author: Daniel K Kalinaki. PHOTO/FILE.

What you need to know:

- Kindergartens charge so much for so little because they are so few. I do not know of any public (government-owned) day care centre or kindergarten, so they are purely profit-driven enterprises.

It costs more to put a child through a year of falling around and crying for no good reason at kindergarten in Uganda, than a year in the leading university, Makerere.

A semester spent at Makerere listening to the droning of professors with PhDs costs about Shs2 million, plus change. Any half-decent kindergarten will charge about the same per term for the privilege of giving your infant a place to take afternoon naps and pick up colds.

I know a few university degrees that are not worth more than a good afternoon siesta, but, on average, most are. The ridiculous value mismatch is a combination of over-pricing at the bottom stage, and under-pricing at the universities.

Kindergartens charge so much for so little because they are so few. I do not know of any public (government-owned) day care centre or kindergarten, so they are purely profit-driven enterprises. They also take advantage of the emotional connection parents have to their children generally, and infants in particular.

Which is perfectly fine. Parents should be free to spend as much money as they want, or as little as they can afford for naps for their toddlers. Inversely, the renewed effort by the government to impose a cap on how much schools can charge in fees is misguided and unfeasible.

Even an identical product like a can of coca cola varies in price in the same market. One customer will pay Shs1,000 for it in a supermarket; another will gladly pay Shs10,000 in a high-end hotel.

Yet education is not an identical product. The subjects might be the same but the teachers are not, neither are the facilities and the overall experience. To demand a uniform price for what is essentially a different product is not practical.

Government can impose some restrictions on the schools it owns. For instance, by allowing higher fee ceilings for schools with certain facilities, or whose teachers are better qualified or more experienced.

It can also impose negative and positive incentives to drive down fees. Investors who borrow cheaper public money to build schools can be required to stay within a fee range or set aside means-tested bursaries for students from poorer backgrounds.

But it is unfeasible to impose a price cap on private, for-profit schools. The government cannot impose a cap on how much money a hotel or a bar can sell a bottle of beer; it must be tipsy to think it can do it with school fees! Neither can it tell a butcher shop how much to sell each kilo of beef. That is counter to the open-market policies we embraced; price determination was left to the market.

What the government can do is to invest in quality public schools that provide a good but affordable education. Previous governments, with significantly less money, were able to do this; why can’t we do this today? If we did, private schools would have to provide a different value proposition to remain in business. In Rwanda the public schools in some areas improved so dramatically, there were reports of parents pulling their children out of expensive private schools as a result.

Decades of under-investment and poor outcomes in health, education and other sectors have provided incentives for private capital to provide what once were public goods, at a profit. Capital has done well from it, not so labour whose wages have remained low or stagnant.

Having privatised health and education, it is disingenuous for the government to now try and impose price caps on what are private enterprises. When schools were shut during the pandemic, some investors turned their buildings into clinics and other businesses. Teachers turned their backs on the profession and went into more resilient industries. As soon as these fee caps make schools unprofitable many investors will move their capital into other areas, leaving the fewer remaining schools to charge even higher fees.

For decades we warned about the need for a social safety net in the form of decent and affordable social services, especially in health and education. We argued that this and a private sector-led economic growth model were not mutually exclusive, but we were ignored. Now we have been laid bare and spread-eagled by the erosion of incomes and the insatiable thirst for profit.

We turned good public education into a private good accessible to only those with cash and turned our schools into profit centres. We cannot turn them back into charities – and certainly not by proclamations and statutory declarations.

Mr Daniel Kalinaki is a journalist and poor man’s freedom fighter.

[email protected]

@Kalinaki