Open defecation should concern all stakeholders

What you need to know:

For Uganda in 2019/2020, hand washing with soap at household level stood at 38 percent in rural areas and 61 percent for urban areas

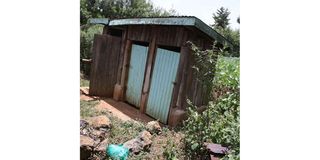

Low latrine coverage in rural areas and generally increased open defecation still haunt Uganda’s sanitation and hygiene situation. From the global perspective, 4.5 billion people still have no access to improved sanitation facilities. Of these, 2.3 billion have no access to basic sanitation facilities and 892 million practice open defecation.

The availability of hand-washing facilities are also still a huge challenge in sub-Saharan Africa where only 25 percent of the population has access to hand washing facilities, with one in four people able to access facilities with water and soap.

For Uganda in 2019/2020, hand washing with soap at household level stood at 38 percent in rural areas and 61 percent for urban areas. Yet NWSC slogan says, “water is life’’ and indeed water has been found an essential factor in lessening the contraction of many diseases including cholera, Covid-19 and Ebola among others

In Uganda, access to improved sanitation facilities is still low, particularly in urban areas, only standing at 36.3 percent, with 12.6 percent of the urban population particularly in slum and semi slum areas practicing open defecation and 30 percent of latrines in rural Uganda very contaminated with human waste.

It is documented that above 78 percent of slum households in Kampala share sanitary facilities yet sharing sanitation facilities has been found to affect cleaning behaviours and maintenance resulting in the abandonment of most facilities thus imploring KCCA management to take keen interest in this issue before the situation runs out of hand.

The fact is that open defecation perpetuates a vicious cycle of disease and poverty and countries where open defection is most widespread have had the highest number of deaths of children aged less than 5 years as well as the highest levels of malnutrition and poverty plus big disparities of wealth.

Diarrhoea remains a major killer but is largely preventable. Better water, sanitation, and hygiene could prevent the deaths of 297,000 children aged less than five years each year. A WHO study in 2012 calculated that for every $ 1.00 invested in sanitation, there was a return of $ 5.50 in lower health costs, more productivity and fewer premature deaths.

Rural Uganda faces a lot of problems caused by poor sanitation facilities such as pollution of water sources, a high rate of waterborne diseases, high expenditures on curative health care, and the threat of reduced educational performance of children attending government sponsored UPE and USE systems through illness, early school dropouts, more especially of girls.

Yet access to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation is a human right where government must muscle financial resources to provide safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation as per the UN signed protocol on sustainable Development Goal target 6.2 which calls for adequate and equitable sanitation for all. It can’t go without mentioning that we have lived in decades of misuse, poor management, over extraction of groundwater and contamination of freshwater supplies that exacerbated water stress.

In addition, Uganda faces growing challenges linked to degraded water-related ecosystems, water scarcity caused by climate change, underinvestment in water and sanitation and insufficient cooperation on trans-boundary waters.

In 2013, the UN Deputy Secretary-General issued a call to action on sanitation that included the elimination of open defecation by 2025.

The world is on track to eliminate open defecation by 2030, if not by 2025, but historical rates of progress would need to double the effort for the world to achieve universal coverage with basic sanitation services by 2030.

Finally, achieving the universal access to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene targets by 2030 would save 829,000 people annually, who die from diseases directly attributable to unsafe water, inadequate sanitation and poor hygiene practices.

Patrick Kajuma Kagaba, MPA Scholar, UMI