Remembering Piero Corti

What you need to know:

- Corti had a vision that Lacor Hospital would provide quality healthcare to the poorest of the poor without requiring them to sell their land or other properties. To him, selling a chicken or two should be enough for one to access medical services; be it surgery or ICU admission.

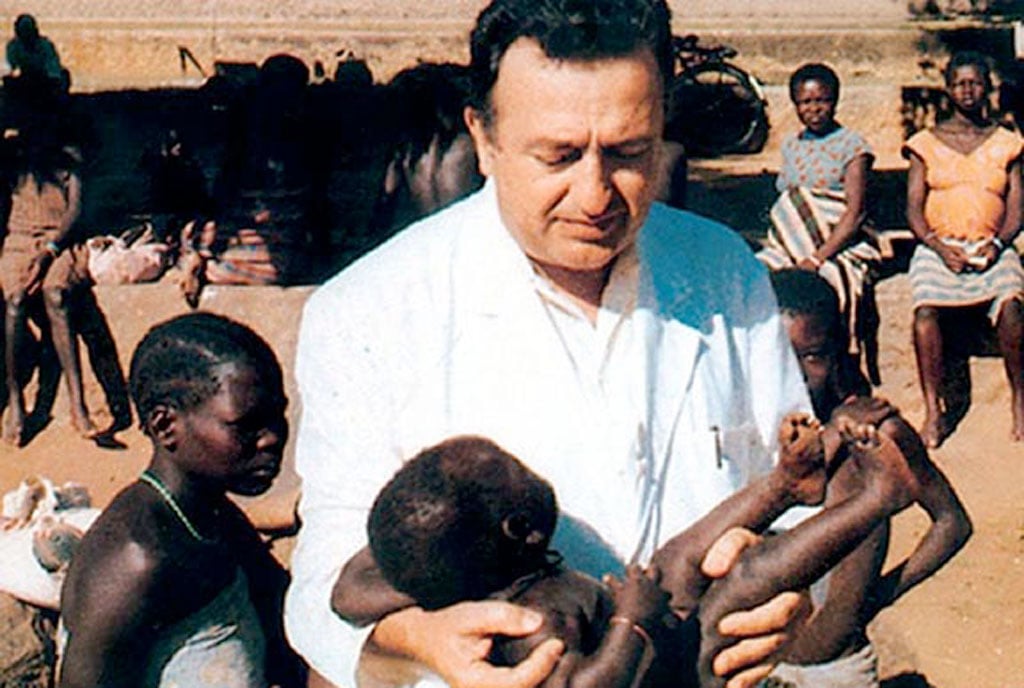

It’s been 20 years since Piero Corti passed on. His is a story of a man who went above and beyond to deliver the best possible care to the greatest number of people at the least cost to the needy. Corti had a vision that Lacor Hospital would provide quality healthcare to the poorest of the poor without requiring them to sell their land or other properties. To him, selling a chicken or two should be enough for one to access medical services; be it surgery or ICU admission.

This became the mission of Lacor Hospital and that explains why the hospital charged only Shs5,000 as consultation fees for Covid-19 suspects and still managed to beat the oxygen crisis in the country at a time when many were charging millions of shillings.

In 1961 Piero Corti, a young Italian paediatrician, was assigned the management and development of Lacor Hospital, a hospital which consisted of one outpatient department and few wards with about 30 beds and few Comboni Missionary sisters who were midwives and nurses, and some local staff trained on the job.

Piero was soon joined by a young Canadian surgeon, Lucille Teasdale. They had met in Montreal a couple of years earlier during their postgraduate studies and had shared their dream of being missionary doctors. Lucille accepted Piero’s offer to get the surgical ward at Lacor up and running for a couple of months but little did she know that this would be a lifelong commitment. They were married by December 1961.

Teasdale would later become the only surgeon in the north in 1979 as the region was cut off from the rest of the world as Tanzanian soldiers advanced after Amin had been deposed. Lucille was the only surgeon in a vast area capable of doing complicated war surgery; most cases were Amin’s soldiers who had wounded one another. Because she had to perform some of these surgeries without protective gear, even at gunpoint, she contracted HIV/Aids, a rare disease with no treatment at the time that would lead her to her grave.

The hospital was located on the escape route used by Idi Amin’s army as they retreated, and was ransacked by the escaping soldiers in the days leading up to the arrival of the Tanzanians in Gulu. An officer of the Tanzanian army stated that St. Mary’s was the first hospital they had found open and operative since they had entered Southern Uganda several months earlier.

In 1986, the Cortis were awarded the Sasakawa World Health Prize by the World Health Organisation for the Primary Health Care programme they established at Lacor.

When Museveni took power and Joseph Kony waged war against his government in northern Uganda, Lacor became a sanctuary for many seeking refuge, hosting as many as t10,000 commuters a night. The peripheral health centers in Opit, Pabbo and Amuru saved the populations from making dangerous journeys to Gulu Town in search of healthcare.

Nevertheless, the LRA rebels would occasionally invade the hospital and eventually they kidnapped Dr. Mathew Lukwiya, the Medical Superintendent in 1991. In the wake of his kidnap, the Cortis prepared for the possibility of evacuation. At the prospect of the complete closure of Lacor, the guerrillas agreed to respect the hospital. The Cortis remained where they were.

Because of this, Piero was awarded the Silver Medal for Civil Merit by decree of the President of the Italian Republic. Lucille was made a Member of the Order of Canada and received several other distinctions for her work with HIV/Aids patients.

Piero and Lucille started working on the project to establish two foundations, one in Italy and one in Canada that could contribute to guarantee the funds, technical assistance and logistical support to the hospital. The two foundations are the reason Lacor Hospital has continued to provide affordable care.

From a 30-bed hospital in 1961, Lacor now has 550 beds, 700 employees, three health center IIIs and a health training institute. It is one of the largest non-profit referral hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa and a satellite training center for Gulu University Faculty of Medicine.

Piero was a visionary. His family background in running a textile industry back home in Italy gave him a business mentality. He had an agreement with the Bishop GB Cesana, the then bishop of Gulu: he would not ask the Diocese for funds but would search for help elsewhere. In exchange the Diocese allowed him to run and develop the hospital autonomously.

Much of Piero and Lucille’s time when not working would henceforth be dedicated to finding the funds and materials needed for the hospital’s survival and development. The Padua-based CUAMM (now Doctors for Africa CUAMM) started sending volunteer doctors carrying out two years’ civil service; this collaboration continued for over 20 years and opened the way for many Italian doctors who still come to volunteer at Lacor to this day.

Alfred Oryem, Communications Officer, St. Mary’s Hospital Lacor