Jobless population still haunts Uganda

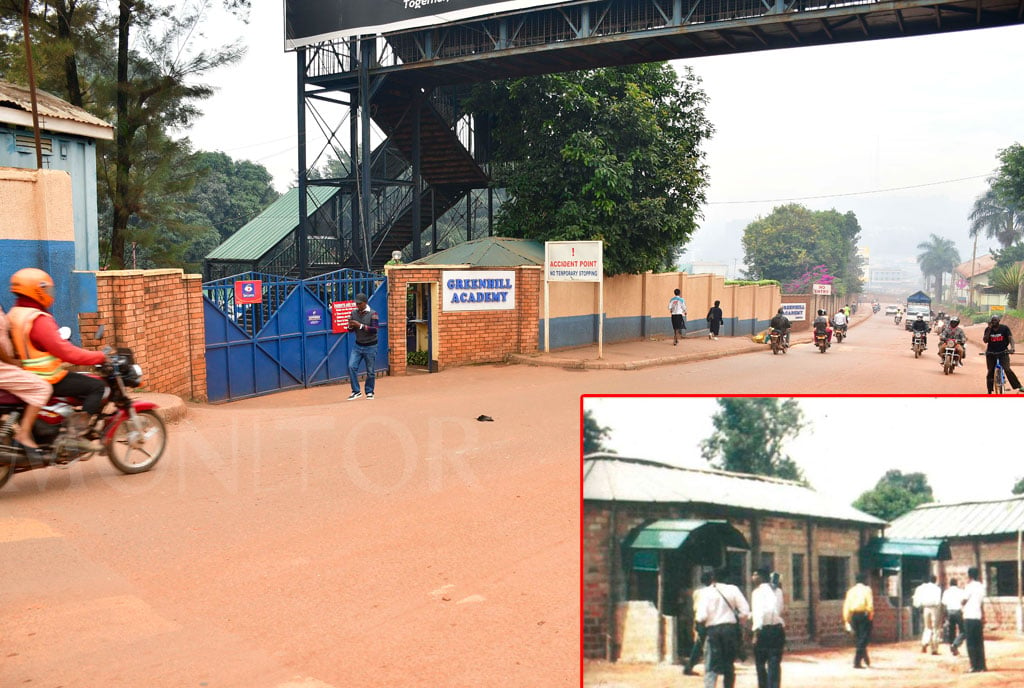

BREAD ON THE TABLE: Many people in Uganda are either unemployed or under-employed, making it a major election issue. PHOTO BY EDGAR R. BATTE

After years of nail-biting in Uganda, Ally Mukasa, 40, a teacher, left the country in 2005 searching for work. He now lives in South Africa. Five years later, he drives his own car and owns a Non-Governmental Organisation in Drakenstein, Western Cape Province —Wagon of Hope Foundation.

Unlike Mr Mukasa, Ms Juliet Nagadya (not her real names), 29, a specialised nurse, resigned her job in Mulago Hospital the same year over “poor pay” and left for the US. She now works as a nurse aide at Bishop Davies Medicare facility in Dallas, Texas. “Before I joined Mulago, I had spent three years walking the streets, doing odd hours in private clinics in Kampala. Later in 2003, Dr Lawrence Kaggwa, the executive director then, allowed me to volunteer in the hospital for about three months without pay until they advertised and I was given a job,” Ms Nagadya said.

“We were being overworked; we were few yet patients were many and they were paying us peanuts. I worked for about one year and left for kyeyo (work abroad) together with my friends. Others stayed and joined us after a year. Life was hard and demands were too many. But life here (Texas) is fantastic and the job is paying handsomely.”

Earning anywhere from $20,000 to $60,000 a year (Shs40 million to Shs120 million -- depending on qualifications), doctors and nurses working abroad seem to be gaining the opportunity of a life time. The same nurse in Uganda would earn between Shs3.5 million to Shs7 million per year—representing a Shs123 million disparity. This goes to the core of employment facing Uganda.

Ms Nagadya and Mr Mukasa are not alone in the Diaspora. They are part of an estimated 700,000 Ugandan professionals who have over the years left the country searching for jobs and higher pay. These Ugandans according to Prof Augustus Nuwagaba, a development analyst from Makerere University, share one thing: they escaped the unemployment, poverty and poor pay across sectors of the economy. It would be interesting to see how the candidates in the 2011 presidential race are addressing themselves to this pressing matter.

A new study by the World Bank titled: “International Migration, Remittances & the Brain Drain,” found that from a quarter to almost half of the graduate nationals of poor countries like Uganda, Kenya, Mozambique, and Ghana live abroad —fueling a vicious downward cycle of underdevelopment and manpower shortages in critical sectors.

Flight of skill

Whereas the government says “brain drain is good for Uganda” in the context of an estimated Shs1.5 trillion remitted to Uganda each year, analysts say a troubling pattern of “brain drain” -- the flight of skilled, middle-class workers who could help uplift the country out of poverty -- is complicating government efforts to develop the country.

The analysts and the civil society are asking voters to push presidential candidates toward addressing brain drain—an endemic glitch that has hit particularly the health sector. However, while the ruling NRM manifesto is not explicit on the issue of brain drain, President Museveni has promised to create more jobs and address abject poverty biting over 10 million Ugandans. This promise, critics say, has over the years remained on paper, fuelling the brain drain.

Even as all the manifestos for the eight candidates pledge to deal with the unemployment crisis and poverty, it’s only the Inter-Party Cooperation presidential candidate Dr Kizza Besigye whose manifesto is explicit on the brain drain problem—once again promising to stop the exodus of Uganda’s top brains.

Acknowledging the problem, Dr Besigye said that 25 years ago Rwandans were flocking the country for jobs but now “it is Ugandans rushing to Rwanda and other developed countries for employment.” He promises to stem the haemorrhage by dealing with the economic factors that drive the phenomenon by, for instance, easing the cost of doing business and restructuring the public service to create more jobs for unemployed graduates.

Statistics from the labour ministry show that out of the 400,000 students who graduate from various tertiary institutions across the country each year, only 8,000 have a chance of being gainfully employed. As of April this year, the number of civil servants in the country stood at only 254,159.

Even after the government lifted a freeze on public servants’ recruitment across the sectors in the country, the situation has not changed much mainly because of the limited absorption capacity that is also complicated by corruption in recruitment.

Other available figures indicate that for every one job that is open, there are at least 50 qualified Ugandans labouring to get it. Labour market experts say that given the wide-spread corruption in the country, even the most qualified for the available jobs don’t get them because the labour market is highly “patronised”—something that can only fuel brain drain.

Shortage of doctors

Discarding the government views on brain drain, Prof Nuwagaba told this newspaper that the country’s doctor to patient ratio currently stands at a worrying 1:36,000, compared to the WHO recommended 1:600. The nurse to population ratio is 1:5,000; and the midwife-to-population ratio is 1:10,000. The ratios vary widely between districts and could be even higher in northern Uganda.

“Brain drain is discounting factors of production and this is not good for the country. The reason we are losing professionals in large numbers is because of one thing: poor pay and unemployment,” Prof.Nuwagaba said. “Uganda is a good country but people are leaving for greener pastures even when we have huge shortages in the system.”

Uganda has the third-highest death rate from malaria on the African continent, with an estimated 320 people dying every day, according to the Ministry of Health. According to the latest Human Resources for Health Bi-Annual Report-2009-2010, about 1,000 nurses have this year alone, left the country for greener pastures abroad. Over 1,500 nurses and midwives qualify every year. “We cannot keep training for other countries when our people are suffering. It doesn’t make sense. The government has to create favourable working conditions for professionals to stay and work in the country. Brain drain is only good for countries with surplus of labour,” Prof Nuwagaba said.

Frustrated doctors

Ministry of Health has reported a shortfall of about 3,000 nurses in public hospitals alone. There are less than 29,000 medical personnel in a country of an estimated 33 million people. Dr Freddie Ssengooba, a lecturer at Makerere University School of Public Health says in a study that due to the lack of a central agency to coordinate information about job availability in the districts and the private health sector, the process of job-hunting has frustrated many nurses and doctors after graduation. But Dr Emmanuel Otaala, the minister in charge of labour docket said: “To us brain drain is not a problem. In fact, as government our policy now is to encourage quality education so as to produce more people with PhDs and export them to developed countries so that we can earn handsomely.” “We don’t lack doctors; we have many of them gambling on Kampala streets because they have refused to work up country. The issue is attitudinal, otherwise, as government we have been progressively increasing salaries for public servants,” Dr Otaala said.

Minimum wage

The Chairman of the National Organisation of Trade Union (NOTU) Wilson Owere observes that lack of a minimum wage in the country and regulations to enforce the employment policy and labour laws had compounded the problem of brain drain. “We want to see policies that will address unemployment and ensure improved working conditions and pay for workers. There is no minimum wage and workers are being exploited. They are talking about prosperity for all when some people are earning less than a dollar and this is unfair,” Mr Owere said.

Mr Owere said: “We want the government to set a minimum wage for all the sectors. Our view is that each sector should have its own minimum wage so that exploitation and poor pay can be checked. “There is a lot of poverty among the people because of the peanuts they are paid that cannot allow them to have basic needs.” But Dr Otaala, however, maintains that a minimum wage won’t ensue from a pronouncement. The minister said as the economy transforms the people will be able to earn handsomely, adding that the “government has not been oblivious; it has been increasing salaries and special attention has been given to hard-to reach areas.”

Remittances

Slow economic growth, population explosion, low pay, and the widening gap between earnings in poor countries and rich countries are some of the key reasons forcing Ugandans to flee their country. The exodus of skilled workers, development experts say, is a symptom of deep economic, social and political problems.