Prime

Patrice Lumumba still shines 50 years after his murder

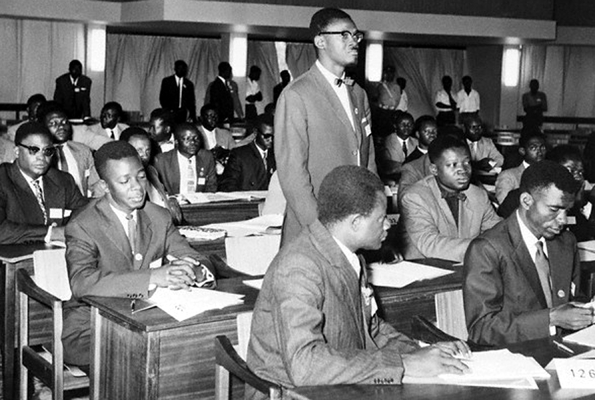

LAST DAYS: Lumumba (STANDING) makes a point during a session in the Congolese parliament in 1960 before he was assassinated.

What you need to know:

On the night of January 17, 1961, celebrated Panafrican Pratrice Lumumba was executed in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) on orders of the US president then. But since then his name has rung out endlessly across the world, he has had streets and avenues named after him in many parts of Africa. As Timothy Kalyegira writes, it is now just over 50 years since Lumumba fell but his name continues to shine brightly:-

In Moscow, the capital of the then Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (the Soviet Union), a university, the Patrice Lumumba University, honoured his memory.

Its name before Lumumba’s assassination had been the Peoples’ Friendship University of the USSR and in 1992 after the collapse of the USSR and the decline in popularity of Communism, the university reverted to the name “The Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia”.

Back home in the capital, Kampala, there was a street in the Nakasero suburb named Queen’s Road but President Idi Amin, the most stridently of Pan-African of Uganda’s heads of state, renamed it Lumumba Avenue. There is, of course, a Lumumba Boulevard in Kinshasa, the Congolese capital.

At Makerere University, the largest of the students’ halls, Lumumba Hall, is named after him. In the then Yugoslavia, a student hall of residence, the The Patris Lumumba Hall of Residence at Belgrade University was named after the slain African hero and still bears his name to this day.

At varying times between 1961 and the end of Communism in 1990, various roads and streets were named after Lumumba in Budapest, the capital of Hungary, Jakarta, capital of Indonesia, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, Skopje in the Republic of Macedonia (once part of Yugoslavia).

More roads were labelled Lumumba the towns of Bata and Malabo in Equatorial Guinea, the Iranian capital Tehran, the Algerian capital Algiers, Santiago de Cuba, in the Caribbean island nation of Cuba, the Lód District of the Polish capital Warsaw, Poland; in the Ukrainian capital Kiev, Morocco’s capital Rabat, Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, Leipzig, the capital of the former East Germany, Lusaka, Zambia, the Tunisian capital Tunis that last week saw its own successful demonstrations against authoritarian rule, in Fort-de-France, the capital of the French-ruled African territory of Martinique, and Antananarivo, capital of the Indian Ocean island nation of Madagascar.

During the 2006 general election in the Democratic Republic of Congo, several political parties during their campaigns portrayed themselves as following in the Lumumba tradition, indicating the continued appeal of the legend in the country.

All present information points to the fact that the United States Central Intelligence agency which on September 14, 1960, backed a military coup d’état organized by Col. Joseph Mobutu, had at least fore knowledge of Lumumba’s murder.

The CIA, according to declassified documents, had on at least two occasions also been given a directive by the US President Dwight Eisenhower to assassinate Lumumba.

Lumumba was arrested and put under house arrest following the coup. After escaping, he was re-arrested by pro-Mobutu soldiers on December 1, 1960 and flown to the capital then named Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). He was executed on the night of January 17, 1961, just over 50 years ago.

Other freedom fighters

Over the course of time, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie became more recognised symbols of the struggle for African and Black freedom, but Lumumba continues to enjoy a cult-like status this month, 50 years since his death.

Even in appearance, mainly because they wore the same type of glasses, Lumumba resembled that other icon of militant resistance to the established order, the legendary Black American civil rights movement activist, Malcolm X.

In fact, one year before his own assassination, Malcolm X described Lumumba as “the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent.” Another of the great Third World heroes and mythical figures, the revolutionary Argentine-born Che Guevara, also in 1964, declared that “We must move forward, striking out tirelessly against imperialism. From all over the world we have to learn lessons which events afford. Lumumba’s murder should be a lesson for all of us.” There is, incidentally, also an Argentine Reggae band that calls itself Lumumba.

Lumumba was, in stature, a cross between a Malcolm X and the South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, or, to some extent, the Muhammad Ali of the 1960s at a time the World Heavyweight boxing champion had just converted to Islam.

Patrice (or Patrick in English) Émery Lumumba was born on July 2, 1925 in the village of Onalua in the Katakokombe area of Kasai Province in the then Belgian Congo (today known as the Democratic Republic of Congo). He was from the Tetela tribe and, as with most Congolese, from a Roman Catholic family. He founded and led a political party, the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) in 1958. He was elected the first post-independence Prime Minister of Congo in 1960.

The enduring popularity and legend of Lumumba reflects the hopes and dreams common among not just the politically active elite of the 1950s, but among ordinary Africans at the time for a just, prosperous post-colonial order on the continent.

It was in this world of a greatly prosperous West amid the wrenching poverty of the Third World and the cynicism of the geopolitical rivalry between the capitalist West and Communist East that Marxism-Leninism took root, a doctrine embraced by Lumumba and other radicals. It is worth speculating about what would have happened had Lumumba not been assassinated.

Disillusionment sets in

Many promising young African political activists of the 1940s and 1950s, when they finally rose to power and became the first leaders of their young nations at the time of independence, disillusioned many of their staunchest followers.

They became the same tyrants, corrupt in every way and cultivating a cult of personality that they had so vehemently condemned in the European colonial masters. Nkrumah himself and one of Lumumba’s successors, Joseph Mobutu (Mobutu Sese Seko) are examples of the charismatic leaders who later became what they had once condemned in the colonial rulers.

It is possible that his tragic early death has helped preserve the myth of Lumumba in a way that might not have been had he governed for about five years and had to deal with the day-to-day administration and brokering of power that is political life.

The short time it took in 2009 for much of the adorning world to get disappointed, and then disillusioned by, the charismatic Black American President Barack Obama suggests that Lumumba as Prime Minister or Head of State would have been confronted.