Surviving stigma caused by mental illness

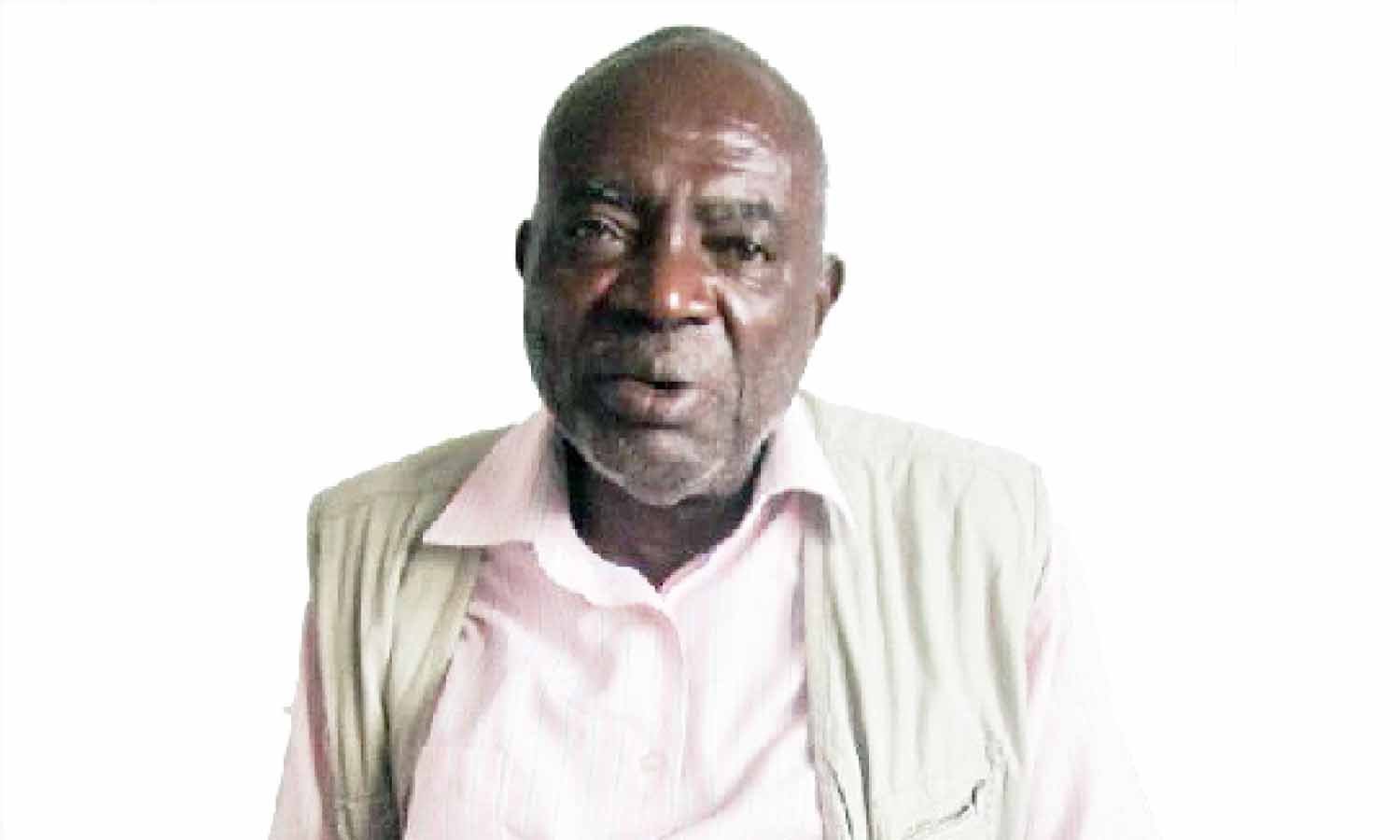

Joseph Atukunda speaks during the interview. He has lived with bipolar disorder for 20 years. Photo by Rachel Mabala

What you need to know:

Mental illness remains a largely misunderstood condition. Although some mental health conditions can be easily prevented and treated, the stigma associated with it keeps many people from seeking treatment, or coming out openly after recovery

When Joseph Atukunda was 20, he was diagnosed with severe depression. At the time, he was a Senior Six student at King’s College Budo.

Atukunda says although he was always outgoing, he started losing interest in things that he had previously been eager to engage in. At the time, Atukunda did not understand or know what the problem was.

“I became withdrawn, fearful and kept to myself most of the time. I started contemplating suicide,” he says.

After being diagnosed with severe depression, Atukunda was put under electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), a common treatment used for people who suffer such depression. ECT works by sending an electric current through the brain to trigger an epileptic fit, with the aim of relieving the depression.

After spending several months on ECT treatment with no improvement, Atukunda was taken to Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital, where doctors diagnosed him with bipolar disorder, a condition in which a person experiences extreme periods of either depression, being too happy or irritable. In addition to mood swings, a person with bipolar disorder has extreme changes in activity and energy levels.

Atukunda says as a student then, at Nkumba University, he often suffered relapses.

“I once found myself in a pond full of mud and students nicknamed it Atukunda’s pond,” he recalls.

Despite his condition at the time, he was able to complete his studies and got a job in Mbarara as an accountant.

In 1997, he got another job which he continued to do until 2000. Then he suffered another severe depression that lasted until 2004. During this period, Atukunda could not keep the job and spent most of his time between home and hospital.

“At the time, I was getting treatment from Butabika. Several months later, I got another job as a logistics coordinator an international organisation,” says Atukunda.

But because of his condition, he could not keep the job for long.

“When I returned to work after treatment, I was demoted. My employers said my former position had a lot of work, which they said may have contributed to my condition,” he remembers.

In 2008, Atukunda met a group of people who had come to Uganda from Heart Sounds, an organisation that works on mental health issues in the UK. Through his interaction with the group, he developed an idea to start an organisation to support survivors and people living with various mental health disorders in Uganda.

A year later, Atukunda started an organisation called Jerendipily center, with the help of friends from the UK. The organisation was later renamed Heart Sounds Centre.

Most of its members are former patients he had met at Butabika hospital.

Treatment

Although Atukunda says he no longer suffers serious repulses or severe cases of depression, he is still on medication, which he gets from Butabika Hospital.

The treatment involves getting a hadol injection every month, as well as continuous review by the psychiatrist.

“The doctors said treatment will be for life but I am optimistic that one day I will get better and stop taking medication,” he adds.

Challenges

For the 25 years he has spent with this disorder, Atukunda says the biggest challenge remains stigma.

“When you recover from a mental illness, many people shun you because they feel they cannot interact with such a person.

Many of my friends have abandoned me as a result of my condition,” he says. Atukunda says the support he has received from family and the counsellors at Butabika hospital is what keeps him going.

Today at 45, he is married with four children and says suffering from a mental health condition does not necessarily mean a person cannot do anything.

He says many mental health disorders can be treated if people seek treatment early enough and stick to what the doctors tell them.

Ruth Katushabe’s story

Ruth Katushabe, 28, started developing mental complications in 1999. “When it started, I could not talk to anyone. Four days later, I started walking naked. My mum even started hiding me away from the public because she could not understand my behaviour,” says Katushabe.

She was admitted to Mbarara Regional Hospital, and spent two months undergoing treatment.

“After I was discharged, I dropped out of school because I could not concentrate on anything I was doing,” she adds. She suffered another severe depression in 2000.

When her condition improved, Katushabe decided to seek help from Butabika hospital, where doctors diagnosed her with bipolar disorder.

She spent two- and- a- half months at the hospital undergoing treatment and counselling.

Katushabe says the treatment from Butabika has been helpful and as a result, she has not suffered a major episode of depression since 2008.

“Alot has changed from the time I started getting peer support and sharing my experience with other members and the public. It has helped me get rid of boredom or slipping back into a depression state,” Katushabe adds.

Medication

“These days, I take medicine once a day, only when I am going to sleep unlike in the past when I used to take drugs five times a day.

Challenges

“The medicine I take makes me dizzy and therefore unable to concentrate at all times,” says Katushabe.

Another challenge, she says is the stigma associated with mental illnesses.

“Most times, people do not understand that you can get a mental health problem, recover and get back to regular work. You hear people calling us mad. Having a mental condition is not the same as being mad,” she says.

Expert view

Dr Derrick Mbuga, the executive director of Mental Health Uganda, an organisation that brings together people with mental illnesses, says alcoholism and drug abuse are some of the contributing factors to the escalating cases of mental health disorders.

“Though the actual number of mental health patients in the country is not known, it is estimated at a ratio of 1:10 ,” says Dr Mbuga.

Dr Mbuga says there are only 26 psychiatrics in the country, yet Butabika hospital alone receives an average of 20 patients a day. He says government needs to train non-psychiatric health workers to reduce congestion at referral hospitals and also tackle mental illnesses when the condition is still in the early stage.

How bipolar manifests itself

Dr Margaret Mungherera, a senior consultant psychiatrist, at Mulago National Referral Hospital, says bipolar disorder is a severe mental condition that changes a person’s thinking, emotions, behaviour and the way they perceive things. She says people with bipolar often exhibit a state of either extreme excitement or depression.

“During the maniac (extreme excitement) state, a person talks and laughs a lot. But they can also be dangerous because they easily destroy property or harm other people,” says Dr Mungherera. In a depression state, a person usually has mood swings, which last long hours.

Dr Mungherera says when a person suffers depression, medication such as antipsychotic can be taken to stabilise the chemical imbalance in the brain. She adds that family and community support is crucial in helping people with the condition live normal lives.

common signs of bipolar

The exact cause of bipolar disorder is not known. But it occurs more often in relatives of people with the condition. These signs and symptoms will help identify if a person has bipolar disorder.

•Daily low mood or sadness.

•Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions.

•Eating problems such as loss of appetite and weight loss, or overeating and weight gain.

•Fatigue or lack of energy.

•Feeling worthless, hopeless, or guilty.

•Loss of pleasure in activities once enjoyed.

•Loss of self-esteem.

•Suicidal tendencies.

•Trouble getting sleep or sleeping too much.

Why you may suffer memory loss

Memory loss or impairment happens when a person is not able to recall certain things, either for a short time, or permanently.

Dr Noeline Nakasujja, a psychiatrist at Mulago National Referral Hospital, says some people may suffer memory impairment but not permanent loss. “It (memory) is something they are able to regain afterward. But memory loss is permanent,” Dr Nakasujja explains.

She says when a person suffers memory impairment, several tests are carried out to establish if they are aware of themselves, their surroundings, or if they are able to correctly identify objects and trace their way around.

Dr Nakasujja says there are two types of memory impairment and loss. One of them is delirium, a short-term acute condition, which happens suddenly as a result of infections such as malaria, pneumonia, meningitis and HIV. It is also common among people who abuse drugs.

Dementia, another type of memory loss is more common among the elderly, affecting mostly people who are over the age of 65. When dementia happens in people who are under 60, it is commonly associated with HIV and failure to adhere to medication. Some forms of memory impairment, according to Dr Nakasujja are due to Vitamin B12 deficiency in the body. This, however, can be prevented if people consume more fruits and vegetables.

“Some people are genetically predisposed to dementia and therefore, it cannot be prevented from happening. But what can be done is to delay its onset by exercising the brain,” she adds.

This may involve engaging in activities such as filling crossword puzzles and jogging regularly.

Prevention

Dr Nakasujja says memory impairment such as delirium is easily preventable.

“When people avoid abusing substances such as cocaine and marijuana, they reduce their risk of suffering from such memory impairment. Avoiding drink-driving and wearing helmets to avoid accidents and head injury is also crucial,” she adds.

For a condition such as dementia, Dr Nakasujja says managing behavioural problems is important.

-Roland Nasasira