Lango schools struggle to cope after 20-year war

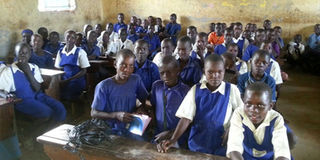

Surge. Pupils attend class at Ocamonyang Primary School in 2016. A drastic increase of school enrolment has been reported in Lango Sub-region. PHOTO BY BILL OKETCH

What you need to know:

- There are only 1,000 teachers for the more than 80,000 learners in Alebtong District.

- The reconstruction programmes, including the Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (Nusaf), Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP) have also motivated parents to make some construction on their own, Mr Okello says

ALEBTONG. Lydia Amony, 10, arrives at school early and waits patiently in her classroom every morning, but finds only fellow pupils.

By 9am, only a handful of her teachers have arrived at her school, Abia Primary School at Abia Sub-county, Alebtong District.

Amony’s fellow-pupils often fight one another, disrupting those trying hard to prepare for their final exams; the Primary Leaving Examinations (PLE).

Most of the days end with Amony having learnt nothing.

“Some of my classmates in Primary Four don’t even know how to read and write. They make noise all the time and I feel sorry because at the end of the term, they will have learnt little,” she says.

But Amony blames the complex problems affecting education in northern Uganda on the more than 20 years of war between the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) and the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA.

Abia is one of the areas that suffered atrocities of the war.

After nearly two decades of war and with warrants of arrest hanging over his head from The Hague-based International Criminal Court, LRA rebel leader Joseph Kony has fled with his forces to a remote corner of the Central African Republic (CAR).

Nevertheless, like Abia, many other schools across northern Uganda were abandoned and suffered damages from the war.

Now that peace has returned across the region in recent years, enrolments have surged, exerting pressure on classrooms and teachers.

This pressure has been heightened by government’s drive to implement free primary education for all children as part of the country’s Universal Primary Education (UPE) programme. UPE was introduced by the government in January 1997 in an attempt to deliver free primary education to four children per household.

In Alebtong District, at least 80,000 children are currently enrolled in government-aided primary schools. But because of the war, many of the schools are struggling.

Mr Nelson Opaka, the head teacher of Abia, says the teachers in Lango Sub-region lack adequate housing, which is traditionally provided by the school.

Currently, Abia Primary School has only 19 teachers.

“The teachers are inadequate and cannot man the entire enrolment of 1,585 learners at Abia. So there is need for us to talk to other relevant authorities so that they help boost the number of staff,” he says.

Finding enough space for the pupils at the school is also a problem although only about 900 of them attend at any one time.

But the problem of inadequate manpower, teachers’ accommodation, furniture and classrooms cuts across the entire northern Uganda.

For instance, there are only 1,000 teachers for the more than 80,000 learners in Alebtong District.

Mr Norman Okello, the former Oyam District education officer (DEO), says the overcrowding in schools is detrimental to the children’s education.

He says in order to boost the standard of education in the region, the government should give more incentives to teachers, increase their salaries, and recruit more staff.

In Dokolo District, Mr Cons Okabo-Opio, the head teacher of Angwecibange Primary School, says while the ideal pupil-to-classroom ratio in Uganda was set at 55 to one, most schools have more than 200 pupils per classroom.

The Alebtong District probation officer, Mr Pius Okabo, says there are fears that some schools could even lose their property as communities try to reclaim land they once leased out to them. Some farmers in Lango want school buildings demolished so that they can farm the land.

Mr Tom Superman Opwonya, the executive director of The Apac Anti-Corruption Coalition (TAACC), suggests that disciplinary action be taken against teachers who miss school.

The Oyam Resident District Commissioner, Ms Gillian Akullo, says it will be hard to overcome the residual effects of the region’s long-running conflict despite the efforts to improve education in the region.

She says the challenges in education come down to poverty and other problems associated with the prolonged LRA war.

But Mr Okello downplays Ms Akullo’s fears, saying with support from development partners, the education system is improving steadily across the region.

He says even some individual schools that used to perform poorly have picked up because of donor contribution.

He cites Minakulu, Ayomapwono, Anyeke, Ngai, Anyomolyec, Otwal, Ogwet, Onekgwok, and Agobadong primary schools that used not to post any First Grade, but are now registering pass grades.

“Even if they are not getting First Grade; the children are not failing as they used to because of these new facilities,” he says.

The reconstruction programmes, including the Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (Nusaf), Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP) have also motivated parents to make some construction on their own, Mr Okello says. Indeed, parents are now constructing not only semi-permanent but even permanent houses in most of the schools within their districts.

The former Oyam DEO says the high dropout rate has come down in most schools in the region because of the new facilities that they now have.

Dickens Emuna, 14, Primary Seven pupil of Abia Primary School, says for effective learning to take place, parents should provide children with enough scholastic materials, school uniform and meals.

“As a parent, you should make sure your child wears school uniform while going to school, to serve as identity,” he said at the belated commemoration of the Day of the African Child at their school on June 27.

“Parents should also be vigilant on gender equality. Both boys and girls should be given equal opportunity. The government should build more pit-latrines, classrooms, and supply adequate desks to schools,” he appeals.

Mr Bonny Ocen Abua, the Alebtong District youth chairperson, says they have been mobilising the community to ensure they support the education of children.

“We are encouraging parents to provide meals for their children while they are at school. We are also using the Church and political leaders to ensure the message reaches them [parents],” Mr Ocen says.