Mailo land is not the problem, but Article 237 of Constitution

The government aim of achieving middle income status for this country may be hampered by its negative attitude towards mailo land and landlords who are wrongly criticised over frustrating investors. Both mailo land and landlords were the bedrock upon which the foundation of country’s economy was built.

By 1966, mailo land accounted for over 50 per cent of the country’s revenue and Luweero triangle alone (Kyaggwe, Bulemezi and Bugerere counties) boasted 48 large scale agricultural estates whose land is today occupied by squatters. These estates were owned by European and Asian investors on land leased to them by African landlords.

It is this system that a senior government official recently described as being stupid without coming up with a viable alternative. This kind of populist posturing on land issues is hurting the government’s credibility and alienating from it a vital constituency. Of particular concern is the government’s intention to amend article 26 of the Constitution to enable it acquire land before compensation in favour of the mighty investors. To justify this unconstitutional venture, a relentless campaign has been mounted against mailo land and landlords, which is bound to backfire for many reasons.

Firstly, while amending Article 26 of the Constitution may be easy to achieve in Parliament, the international repercussions for the country have not been taken into account. Article 26(1) and (2) of the Constitution repeat almost verbatim the provisions of Article 17(1) and (2) of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Sub-article (1) of the Declaration provides: “Everyone has a right to own property alone or in association with others.” Sub-article (2) reads “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of property.” Taking over property without the owners’ consent as the government proposes will offend these provisions.

Secondly, taking over property and giving it to foreigners as investors was tried in the early days of colonialism by Commissioner (Governor) Harry Johnson, but he was stopped in 1915 by the Secretary of State in London, who also ordered that all grants, which had been made, should be converted into 99-year leases so that at the end of the period, the land would return to the African owner or his successors.

It sounds a bit surrealistic that one hundred years later, an African government is planning to take over the same land from Africans and give it to non-Africans in perpetuity.

Lastly, land vested in the government has been abused by its minders. For example, plots at Namanve Industrial Park were acquired by individuals at giveaway prices, who then tried to resell them at unreasonable prices, which drove away investors.

Land given to the government for public projects by people like Sir Apollo Kaggwa (Butabika), Yusufu Musajjalumbwa (Namulonge), Sepririya Kaddumukasa (Nsambya) and Samwiri Mukasa (Mulago) have all been corruptly given away to individuals to the exclusion of successors of the original owners.

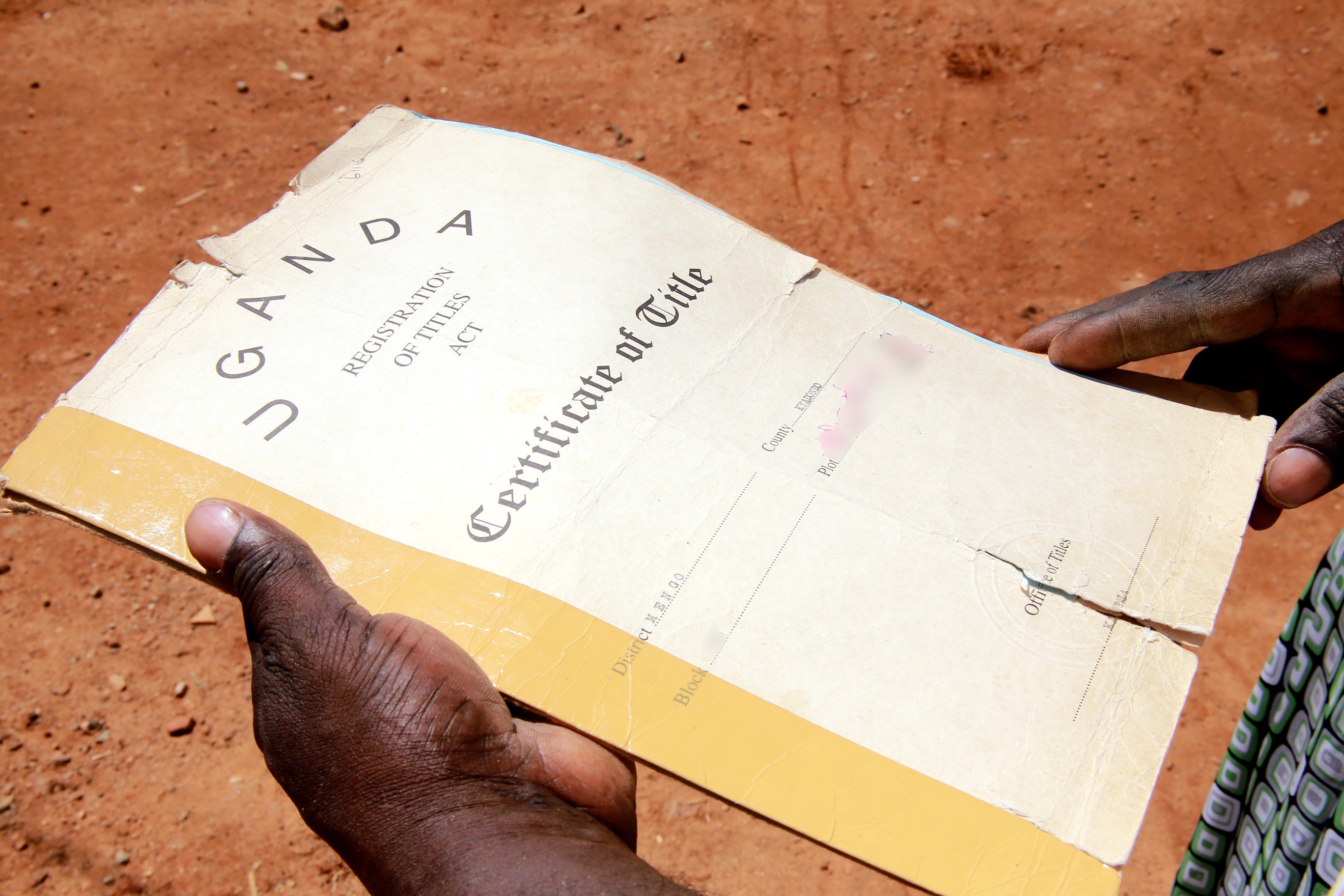

We should accept the reality that Article 237 of the Constitution and not mailo land or landlords is at the heart of government’s land problems. The article provides that all land belongs to the citizens of Uganda and shall vest in them according to the land tenure systems provided for in the Constitution.

A tenure system must come from a higher interest known as the sovereign or radical title. After independence, the radical title was vested in the State, but now there is no such title.

The term “citizen of Uganda” is not a corporate entity capable of owning or disposing of land, which means that whenever government needs land, it must acquire it through the four tenures. This problem was not created by mailo land.

Mr Mulira is a lawyer, [email protected]