Uniting East Africa through theatre

What you need to know:

While they shared light moments, recapped favourite shows and discussed what could be done better next year, the fruit of the cross border exchange that the festival has created for East Africa in Kampala was evident

It is the norm for all successful events to end with dancing. The Kampala International Theatre Festival was no different.

It gathered actors, playwrights and directors for a closing event at CICP, National Theatre, to carnival with their audience, after performances that left a marked inaugural theatrical journey by Sundance Institute in East Africa and Bayimba International Festival.

While they shared light moments, recapped favourite shows and discussed what could be done better next year, the fruit of the cross border exchange that the festival has created for East Africa in Kampala was evident.

Ten plays were showcased from around East Africa.

Strings (Uganda) and Black Maria (Kenya) were a work in progress.

Rogers Othieno, a Kenyan director, said working with a Ugandan cast on Angella Emurwon’s Strings was revitalising. It opened him up to new talent and the script was rewritten during rehearsals to make it work.

Wesley Ruzibiza, the director of Radio Play from Rwanda, agreed that they too did a few changes with the play to make it relevant to Uganda.

Relevance

The exchange created amazing partnerships between artists, such as Gladys Oyenbot and Phillip Luswatta in Ethiopian play Desperate to Fight. Oyenbot said Meaza Worku, the playwright, overlooked “her dark Ugandan self, despite having written the play in Ethiopia, the land of beautiful long-haired women”.

“Working with Phillip, who has been in the industry longer, yet he did not intimidate but welcomed me, was worthwhile,” she said, resounding Esther Tebandeke’s appreciation of the festival’s marriage between the region’s established playwrights and actors with those starting up in the industry.

The selected pieces portrayed new forms of theatre, with actors reading scripts in hand over a stand.

Most plays such as Africa Kills Her Sun were delivered with infusions of dance and music. A rich cultural exchange was manifest in the multi-lingual plays in French, Kiswahili and English.

Easy stories

Each story proved pertinent to Africa as several people found the stories relatable. An overwhelmed Jane Kamau said Sitawa’s story, Black Maria on Koinange Street, is a second person narrative of a Kenyan middle class woman that spoke directly to her.

“The power of the visual through the reading created images, and the facts are so real,” she said.

South Africa’s Ster City exposed issues of apartheid that most Ugandans know, but never experienced through an original artist’s point of view.

Faisal Kiwewa, the director of Bayimba Foundation/co-director of the festival, envisions the festival as a networking base that allows artists understand the works of each other from a different context.

Challenges

Despite the festival’s success, Kiwewa says the audience was good but comprised about 60 per cent Europeans and 40 per cent Ugandans. This remark retorts observation by several critiques who felt that theatre in Uganda has been dying out; reason why a few Ugandans turned up for the festival.

Alice Lwanga, a radio drama consultant, who role played a neighbour in Strings, said given this year’s quality international productions, one can only look forward to November 25 – 29, next year.

Africa Kills Her Sun

Two men clad in yellow outfits emerge from the dark singing a song that evokes sadness.

They are accompanied by a woman who leads them in singing. They are sad because it is their last day alive. They will be executed the next morning. Shot in front of a crowd at a stadium.

This is a brief intro that ushers us into the play Africa Kills Her Sun, an adaptation of Nigerian activist Ken Saro-Wiwa’s short story by Mrisho Mpoto, Elidady Msangi and Irene Sanga from Tanzania.

In a society where everyone has a price, even justice can be bought and a police officer, who is charged with the responsibility of keeping law and order, is not spared, not even the High Court judge. This is what happens in our society today.

Corruption is portrayed by two actors Mpoto, an ambassador of Ebola in East Africa and a household name in Tanzania, together with Msangi.

The play’s poetic style in Kiswahili and storytelling, coupled with the stage set up and lighting, helped to weave a great plot and differentiate the various scenes in the play.

[By Jonathan Adengo]

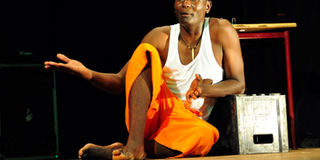

Strings

The familiar plot immediately draws you to the play. Written by Angella Emurwon,

Strings tells of a family’s plight when the head, Baaba, travels for kyeyo. Maama keeps his memory alive through his 20-year absence with make-believe stories for their children and her bed warm with his brother, Uncle Lokil.

But what happens when Baaba decides to come back? How will Maama juggle the men in her life and tell her children the truth?

Read by a captivating cast of Ugandan actors, including The Hostel series actress Diana Kahunde, the humour and wit in the script sets it apart as both entertaining and mind stimulating.

[By Monitor Reporter]

Black Maria on Koinange Street

Sitawa Namwalie, a Kenyan poet, achieved tremendous success reading her first play Black Maria. The lack of stage acting left nothing wanting as she simultaneously shifted between two seats for change of scene, giving visual life to each of the university girls (affluent Nerima, Maria of coastal blend, Judy the tomboy, Charity the very decently dressed smoker and Wangari, a beautiful African princess), who fold within the dark experience on Koinange street

The essence of the title unveils in scene eight, when all the action wraps up in the back of the Black Maria (a police car) driving down to the station after a police night raid in 1980’s Nairobi. The scene explores prostitution and human folly.

Nerima’s new life in the city, after her parents decide that she should study in Nairobi and not USA or the UK, forces her out of the comfort and protection of her privileged middle class home.

At university, her insatiable need for elegance, multiple designer wardrobe and the need to call home so the driver picks up the laundry is absurd. Her encounter with the police teaches her that being wealthy or a university student preparing for final exams but forgot her identity card, does not save you from the wrath upon Koinange.

Sittawa says she wrote about the student years which are often forgotten, placing the story in the iconic Koinange, a red-light district.

The dialogue is witty, awash with sarcasm, humour, exploring incredible African cultural allusions, university norms, light confrontation between Arts and Sciences and the middle class society in contrast with the unprivileged.

[By Douglas Sebamala]