Poetry in the eye of a child

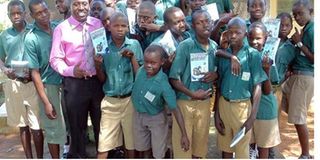

Philip Matogo, coordinator of the Songs of Kiguli project, poses with pupils brandishing copies of their latest anthology. Photo by John K. Abimanyi.

What you need to know:

This collection of poetry overflows with raw innocence of childhood.

Although your default expectations for a children’s anthology thrust onto your laps could be to find an overly edited work, which has taken on the identity of whichever editing hands managed it, this collection overflows with the raw innocence of childhood. The pupils of Kiguli Army Primary School open up their lives and invite you on a journey that charts the heights of their hopes, dreams and aspirations, and explores the depths of their fears and drawbacks.

To understand this anthology, it is important to understand these young poets’ background.

Rural background

Kiguli Army Primary School is found in a rural setting, of Nakasongola District, away from the bustling fast pace where urban Ugandans live. It can only be the case that Play Station game consoles and Barbie dolls are not the defining childhood that these children have endured.

And it shows. For themes like stepmothers, nature and environment, farming, poverty, disease, gender equality and many within this wavelength, fill the anthology’s pages, a sign of the sheer authenticity of the work.

Some are surprising in their ability to infect with hopefulness. One of these is Dream, by 14-year-old Julius Akiiki. In an obvious reprise of Martin Luther King Jnr’s I Have a Dream Speech, it features a child’s dreams of a society where the family functions, and the girl-child does not slide down the wedge of gender inequality.

“I have a dream,” he writes, “My little boy will not despise my little girl, because she is a girl.”

Akiiki says he wants to be an engineer someday; but he will keep on writing poetry.

Some speak of an in-held sense of despair at a given situation. Consider, for instance, Lucky Acheng’s Stepmother, which reads, “Oh, stepmother, you are so bad; you kill us, you deny our rights, rights like education.”

Happy Morjine uses rhyme to good effect on the poem, Hunger. “Hunger, hunger; you make us suffer; suffer like a burglar; being eaten by a panda.”

These are, of course, not refined poets. But the makings of a poet are there for all to see. You can read it in the choice of rawness of feeling, in the choice of phrasing to create rhythm and rhyme.

In its second year now, the project has etched the art of poetry hard into the pupils’ hearts.

Happy Kamara, 12, talks about poetry’s ability to free the soul. “Poetry has changed my life, because now I do not think about so many sad things. I just write them down and feel as if I am free.”

Writing poetry does not come easy; but the pupils work hard at it. “It takes a lot of concentration to write a poem. Sometimes I miss lunch, thinking about what to write,” Akiiki says. “It takes good English to write poetry. And a love of life.” Contrary to this, Winnie Natamba says it is easy. “Writing a poem is easy,” she says, “because you write about your life and what you have known.”

The children seem to have mastered this well, writing from the heart and allowing their emotions to rule. It is this that makes their anthology rich and real.

[email protected]