How gold scandal case against Amin, Obote collapsed

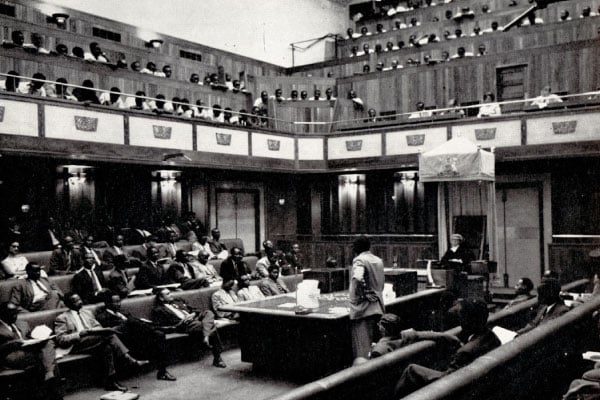

Search. An illustration of MP Alex Latim inspecting a Land Rover suspected to be carrying ivory at a hotel in Kampala. ILLUSTRATION BY IVAN SENYONJO

What you need to know:

- Part II. In its 800-page report, the commission of inquiry stated that Mityana MP Daudi Ocheng, with the exception of Col Idi Amin’s bank statement, had no personal knowledge of the subject matter of the allegations.

Part I:

On February 27, 1966, a few weeks after the motion implicating ministers as accomplices in the alleged looting of gold was debated in Parliament, then Internal Affairs minister Basil Kiiza Bataringaya issued Legal Notice No.1 of 1966.

It created a commission of inquiry whose terms of reference were to inquire whether Col Idi Amin, then prime minister Milton Obote, ministers Felix Onama and Adoko Nekyon received gold, ivory, coffee and money from DR Congo.

The commission was also to inquire into allegations of a conspiracy to overthrow the Constitution and finally a conspiracy to abrogate the Constitution. The legal notice gave witnesses the right to representation when they appeared before the commission.

The three-man team was headed by Justice Sir Clement Nageon de L’Estang who was the vice president of the East African Court of Appeal. Other members included Justice Henry Ethelwood Miller, a judge of the High Court of Kenya, and Justice Augustine Said, a judge of the High Court of Tanzania. Samuel William Wambuzi was the commission’s secretary while a one Rakin was its counsel.

The commission commenced on March 7, 1966, laying down the procedural guidelines. Obote, Onama and Nekyon were represented by John Williams QC and A.R. Kapila. Col Amin was represented by Anil Clerk, Daudi Ocheng by Wilkinson and C.K. Patel while the Commercial Bank of Africa was represented by Mr Keeble.

The first three days had no witnesses coming forward, not even the MPs who demanded for the commission to be instituted.

Ocheng went to London a few days before the commission started its hearing. When contacted by the commission, he pegged his return to government’s willingness to give him a ticket back to Uganda. He would later return and testify.

Report

In its 800-page report, the commission stated that “Ocheng testified at length. He candidly admitted that with the exception of Col Amin’s bank statement, which was the only concrete evidence in his possession, he had no personal knowledge of the subject matter of the allegations.”

The commission heard that Stephanus Martinus Venter, then manager of Commercial Bank of Africa Limited, was approached by a middle man acting on behalf of Col Amin and the government of Uganda.

It was claimed that Obote himself wanted Venter to find a buyer of the gold in Switzerland urgently. However, Venter’s evidence, the commission report says, was “full of inconsistency and very much uncollaborated.”

Ivory

Amin’s name was mentioned in two ivory incidences the commission inquired into. In 1964, a heap of ivory suspected to have come from DR Congo was cited at Vurra customs post.

Appearing before the commission, a one Ezara Mukoza said he thought the ivory came from DR Congo but did not know to whom it belonged or where it went.

The commission’s report says “there was nothing to connect this ivory with Col Amin.”

In the second incident, MPs Alex Latim, Jino Obonyo and Gaspare Oda told the commission that they were tipped off about the presence of three Land Rover vehicles with ivory parked at Amber Hotel in Kampala belonging to some Congolese.

The commission’s report says the three legislators went to the hotel but never saw the ivory.

“I stopped by one of the Land Rovers on my way out and introduced my hand into the tarpaulin because I could not see inside because of the dark. I touched something which felt like an ivory tusk,” Latim told the commission.

The commission was told that later that night Amin came to the same hotel in the company of Robert (Bob) Astles and left in the night with the Congolese and their Land Rovers.

The report concluded that “there is nothing to show that Col Amin obtained possession of the contents of those trucks for his own purpose.”

Col Idi Amin (left) and Bob Astles. The commission was told that Amin was in the company of Astles the night he visited the hotel where the Land Rovers were parked.

Money

As early as 1964, Congolese rebels purchased commodities from Uganda. The in-charge of the procurement was Tony Nyate.

The commission heard that in November 1964, Nyate wanted to buy a jeep for his group but failed and instead left Shs10,000 with Amin as deposit in case Amin found one.

Nyate told the commission that when the Uganda government made Amin their liaison person, they started sending him money for their purchases.

“There was a gentleman’s agreement that Col Amin would receive and bank in his own name in a bank of his choice all the funds he received and used such funds to purchase on instructions from me such articles or commodities as were needed by the Congolese from time to time,” Nyate said.

The commission further learnt that in January 1966, Nyate gave Amin Shs480,000 for purchases. This was part of the money Ocheng alleged was the loot from the Congo.

“According to Nyate, he received all the goods he ordered from Col Amin and as far as he is concerned, he is satisfied that Col Amin has accounted for all the funds received,” states the commission’s report.

On the allegation that Amin and other government officials received money from Congo, the commission concluded: “We are satisfied that Col Amin did, in fact, receive money in large sums from the Congolese revolutionaries through their treasurer, Mr Nyate. We are not prepared to say he appropriated any part of it to his own use since his principals appear satisfied with his conduct.”

On the allegations that prime minister Obote and his two ministers benefited from the alleged loot, the commission found no evidence as neither the gold, ivory, coffee nor the money as assumed in the accusations actually ended up in the hands of Amin.

“There is, in our view, not a little of evidence that they or any of them did and allegations appear to be based solely on alleged failure or undue delay on the part of government to inquire into the allegations against Col Amin, thus giving currency to the suggestion that he was being protected for some ulterior motive,” the commission ruled.

On the conspiracy to abrogate and overthrow the Constitution of Uganda, the commission said “we are not satisfied that there was any conspiracy of plot, or plots, as alleged in the allegations.”

This conclusion was based on the denials of the lead witness William Oryem whom Ocheng had presented as having seen Amin go to the forest in Mbale where the alleged training of 70 youth was happening.

Findings

In summing up their findings, the commission stated that “the allegations of the receipt by the honourable prime minister, the honourable Onama, and the honourable Nekyon of gold, ivory, money and other property from the Congo are totally unsupported by evidence and completely unfounded. Col Idi Amin received approximately Shs480,000 from the Congolese revolutionaries for which he has duly accounted for.”

“We are satisfied that if there was any looting by Uganda troops from the Congo in the course of the military operations, in which there is no evidence, Col Amin was not a party thereto.

“We are not satisfied that there was any conspiracy, plot or plots between the prime minister and some of his ministers and Col Amin to abrogate the Constitution or overthrow the government of the country.”

Commenting on Ocheng’s behaviour as a Member of Parliament, the commissioners said: “We are not concerned with the conduct of parliamentary proceedings in Uganda, or the behaviour of members of that Parliament, we cannot help remarking that the absolute privilege attaching to everything that is said in Parliament must not be taken as licence to make unfounded accusations against any person either inside or outside Parliament.”