The Rwanda-Uganda sphinx

On my most recent research trip to Rwanda (in July last year), I ran into some rather strange encounters. At the Kanombe International Airport, an immigration officer asked if I work for the government of Uganda. His question wasn’t without basis, but I felt scandalised. It took a while for me to get cleared. Questioning and consultations before I was let in.

Later, I spoke to some Rwandan friends about the airport experience. They were not surprised. Something was not right. On my schedule was an interview meeting with then minister of Defence, Gen James Kabareebe.

It was meant as a follow-up to a 2016 conversation I and some colleagues had with him. On that occasion, we also spoke to President Paul Kagame about the transformation of civil-military relations in Rwanda.

This time, the meeting fell through. Despite prior assurances by his assistant before I arrived in Kigali, Gen Kabareebe was unavailable to meet with me. At that time, there was talk of Ugandans getting kicked out of their jobs in Kigali and hashed tones of growing hostility between Kampala and Kigali.

So, what is the source of the polluted environment building up?

I sought answers from a few individuals I have known in Kigali over the years. I couldn’t get a straight explanation. One senior government official, a vociferous defender of Kagame, took the angle of intra kindred animosity. Puzzling.

I had a long discussion with a smart young man who runs an influential online news outlet. He had a somewhat conspiratorial theory. Apparently, it had been determined that Uganda had the highest concentration of vitriolic and hostile online activity, primarily social media, directed at the Rwandan government.

If this were true, I asked him, why would that be the basis of deteriorating relations between the two governments? To him, and arguably many in the Rwandan government and intelligence circles, this was evidence that Uganda was hosting Rwandan dissidents and, therefore, must be seen as a hostile State. It is the same charge Uganda made against Rwanda in 2001.

I pushed back a little, arguing that Uganda in all likelihood, has the biggest number of Rwandan immigrants, refugees and Ugandans of Rwandan descent, which would naturally mean opponents and critics of the Rwandan government are likely to be more in Uganda than, say, Kenya.

Even then, some folks chattering on social media wouldn’t amount to a security threat, I reasoned. He was not persuaded. He ended with a big brush stroke: Ugandans don’t want to accept that their government is against Rwanda. Apparently, Ugandans are so patriotic that when it comes to issues with Rwanda, they stand firmly on the side of their government! I was blown away by this as I had no idea I was blindly patriotic considering my views on Uganda’s current ruling regime.

There is something utterly mind-boggling about Rwanda-Uganda inter-state relations. In 1999 and 2000, armies of the two countries had deadly military confrontations in the Congolese city of Kisangani. It was the lowest point for countries that have both a deep social bond and an even deeper politico-historical affinity.

The political organisation and its armed wing that captured power in Rwanda in 1994, was born directly from the current Uganda political establishment. This should mean that the two regimes have an unbreakable bond, but it is ironically a big source of animosity. The Rwandan leadership has always protested perceived paternalism coming from their erstwhile Ugandan benefactor-ruler, Mr Museveni, and other current or former senior military and intelligence honchos in Uganda.

Part of the friction emanates from asserting Rwandan sovereignty and for Kagame to be treated not as though he were still Museveni’s junior commander, his ‘boy,’ but as an equal Head of State.

I was told of a big-ego retired NRA major general, who went to Kigali in recent years. He wanted to demand his way to meeting Kagame without due regard to the motions and procedures that go with getting access to a Head of State. He was snubbed and left furious. By contrast, the Ugandan military and intelligence establishment, or at least sections, are suspicious of the Rwandan government exploiting, for malign purposes that betray disrespect, the historical connections, specifically Rwandans having been (and perhaps still are) part of Uganda’s armed and security establishment.

Whatever the grievances on either side, I told my Rwandan hosts and friends that an outsider like me, outsider to ruling groups in the two countries, I just couldn’t get to terms with the simmering tensions. Why? In recent weeks, we have heard quite a bit of bellicose rhetoric and less than veiled yet very serious accusations.

There was some blatant name-calling in 2001. We seem to be getting closer to that. President Kagame is the current chair of the East African Community. That should mean he holds the levers of diplomatic power in the region. But does the Ugandan ruler look at him in that light?

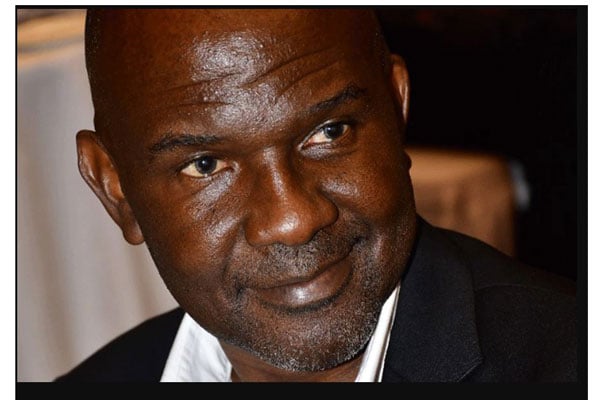

Dr Khisa is assistant professor at North Carolina State University (USA).

[email protected]