Prime

The great Buganda land grab of 1900

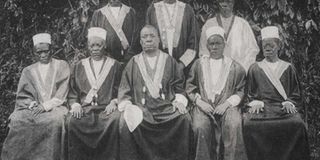

Regent Stanislas Mugwanya (centre) with other Buganda chiefs in the 1890s, during the reign of Kabaka Daudi Chwa II. Regents and chiefs were beneficiaries of land distribution following the 1900 Buganda Agreement that rewarded them for their collaboration with the British. COURTESY PHOTO.

What you need to know:

The agreement allowed an estimated 300 families of chiefs and other notables to take over more than half of Buganda’s productive land.

Kampala

The 1900 Agreement might have given Buganda a privileged position in the Uganda Protectorate that it would continue to enjoy throughout colonialism but it was also the biggest land grab in contemporary history.

The agreement cemented British authority over Buganda but that was a fait accompli, coming as it did 10 years after the first treaty putting the kingdom under the protection of the British, and almost a year after Kabaka Mwanga was captured and his rebellion broken up.

It was the clauses on land redistribution that had the biggest impact on the kingdom and, ultimately, the country that would become Uganda. Land in Buganda had always been a political and economic tool of control, held by the Kabaka in trust for his people, and through his chiefs and clan leaders, but generally owned by the people.

Authority over land was tied to offices; chiefs who lost favour with the Kabaka and their positions would lose control over the land and, by extension, their people who lived off it.

Thus, the first impact of the 1900 Buganda Agreement was that it broke this bind and “divorced the ownership of land from political responsibilities, and most radical of all, land could now be bought and sold like any other commodity”, according to Prof. Samwiri Lwanga, a historian and author on Buganda.

Secondly, the agreement commoditised land. It went from a common resource shared by all under the guidance of the Kabaka, to a commodity that could be bought and sold, like cattle or beads.

Under ordinary circumstances, the free ownership of land ought to have encouraged its more efficient use and would have prevented the arbitrary eviction of peasants by whimsical chiefs. In 1895 William John Ansorge, who was then the acting commissioner in Buganda, had introduced a freehold land tenure system opening up land ownership to all but this had been swiftly defeated by Mwanga and loyal Baganda.

It probably could have worked under the 1900 Agreement. However, the agreement was a victors’ party, made between British officials who were keen to cement their rule indirectly through pliant collaborators, and local chiefs led by Katikkiro Apolo Kaggwa, who had succeeded in their palace coup by ousting Mwanga once-and-for-all, and now sought to cash in their political chips.

In the background were the Christian missionaries who were keen to get a piece of the action. Not only did the missionaries help negotiate the agreement and witness it, Prof. Lunyiigo notes that Bishop Alfred Tucker “pressed Johnston for a higher allocation of land for the chiefs brushing aside the plan for proprietary rights for peasants”.

Chiefs scramble for land

Apart from the 10,500 square miles taken by the Protectorate government, and land given to the Kabaka, the royal family and his regents, 1,000 chiefs and private landowners were allocated a share of 8,000 square miles.

Although the Lukiiko was given powers to carve out this land, it was populated by the very chiefs and prominent persons supposed to distribute the land. As the Kabaka, Chwa II was an infant, the three regents; Kaggwa, Stanislaus Mugwanya and Zakaria Kisingiri had filled the Lukiiko with their cronies and allies who all jumped into the land grab.

The 1900 Agreement specified that these chiefs and landowners would receive the land that was in their possession but Prof. Lunyiigo argues that this was a breach of the agreement because whatever land they had was held in trust for the people of Buganda. “This was the crux of the land settlement in as much as it concerned the Baganda beneficiaries. Right from the beginning they acted in breach of the agreement,” argues Prof. Lunyiigo.

“If this clause had been strictly followed, the land settlement would have been stillborn but the Lukiiko had been transformed from a King’s levee into a veritable den of thieves, and, led by Apolo Kaggwa, proceeded with alacrity to expropriate the King’s land held in trust by him for his subjects.”

What followed was a scramble by the chiefs and other ‘prominents’ to carve out and divide the 8,000 square miles amongst themselves, under the direction of the Lukiiko. The chiefs and notables allocated land to themselves, relatives, friends, and their children, including those who were unborn.

Such was the scramble for the land that a directive had to be passed limiting allocations to children who had not yet been conceived and Kaggwa spent six weeks, “working day and night” to cut the claims down from 3,945 that were submitted to 3,700.

Prof. Lunyiigo argues that, considering the relatives and children included into the list, this figure reflected only about 300 families that, almost overnight, came to own more than half of all the productive land in Buganda.

This had several political and an economic impacts. First, it created a permanent landed gentry in Buganda that, in some cases, has continued to prosper off its good fortune and the land it brought in 1900 to this day.

It thus provided the first lever of social and economic mobility in colonial Buganda for those families that benefitted and would set the foundation for a cash crop based economy that produced what it did not consume and consumed what it did not produce.

Kaggwa’s mega grab

It also changed the economic structure of the country as peasants found their old obligation to the king replaced by an obligation to the crown and the taxman. In working the fields to pay off their tax obligations, the first seeds of independent political consciousness would be sown and sprout shortly after.

For one man, however, the land bonanza completed his power politics and the most astonishing palace coup in recorded Ugandan history. After taking political power from the Kabaka, Apolo Kaggwa now found himself one of the biggest land owners and needing to have the law changed to allow him hold his vast estate.

While many of Kaggwa’s 100 square miles had been honestly, albeit fortuitously received, a large chunk was the result of cunning calculation and borderline theft. Like many leaders who would follow, Kaggwa had mastered the dark arts of land-grabbing.