Prime

How Uganda Agoa ban impacts East Africa investments

Buyers pick clothes from Green Shop, a modern second-hand shop in Kampala on October 7, 2023. Uganda could still trade with th US, but the products will attract normal taxes. PHOTO | AFP

What you need to know:

- Nelson Ndirangu, an international trade expert and formerly Kenya’s chief negotiator at the World Trade Organisation, told The EastAfrican that Uganda could see it coming and so it is possible that the industries could have adjusted to the situation.

- The private sector also termed the US move political, as Agoa has failed to lift Uganda out of poverty.

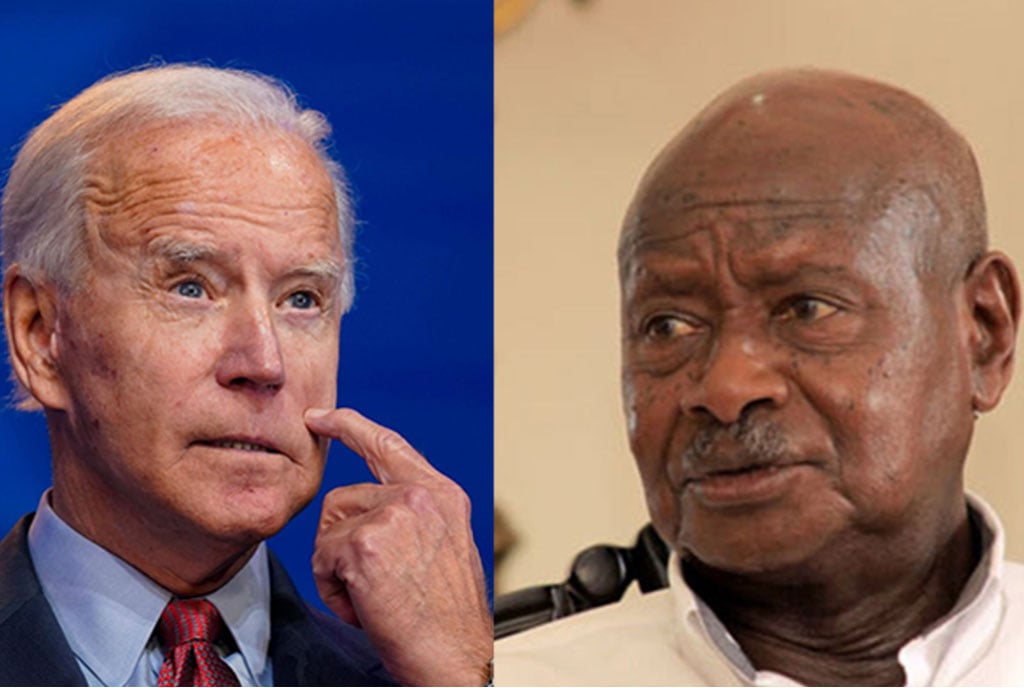

The decision by the Biden administration to kick out Uganda from its African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) programme could have far-reaching consequences on the investment climate in the East African region.

The impact could go beyond the East African region, trade experts say, and Kenya and Tanzania are poised to benefit from the “spoils” if they come up with strategies to woo US corporations moving out of Uganda as a result of Washington’s action.

There are also those of the view that should Uganda lay its strategy properly, its pharmaceutical industry, in which the US government has heavily invested, could be available to African and European investors.

The move could also affect the East African Community’s Rules of Origin as the US could block goods from the EAC partner states produced using raw materials from Uganda.

Washington officially struck out Uganda and three other African countries —Central African Republic, Gabon, and Niger — from Agoa from January 1, effectively ending Kampala’s ability to export certain commodities to the US duty-free.

Nelson Ndirangu, an international trade expert and formerly Kenya’s chief negotiator at the World Trade Organisation, told The EastAfrican that Uganda could see it coming and so it is possible that the industries could have adjusted to the situation.

“There is a possibility that some of the companies could translocate to Tanzania and Kenya – low-cost countries,” he said. “In Kenya, we only utilise a few of the tariff lines out of Agoa’s 6,000. Therefore, those in Uganda, if they are doing tariff lines that Kenya is not making use of, will find a niche market in the country.”

Boasting a pool of more than 6,000 eligible products, Uganda’s exports to the US included coffee, spices, art and antiques, precious metal and stone.

In terms of goods and services, some of Uganda’s imports from the US are agricultural inputs, aircraft, machinery, electrical machinery and medical instruments.

According to Susan Muhwezi, President Museveni’s senior adviser on Agoa and other trade related matters, removing Uganda from Agoa “will damage the livelihood of producers and traders of coffee, cotton, vanilla and other goods and will amount to violation of human rights.”

Uganda has lost export business worth millions of dollars. In the last financial year, Uganda’s exports to the US under Agoa amounted to $8.2 million, out of the total exports to the US in the same period, totalling $70.7 million.

“As it concerns the Rules of Origin under the Agoa, the US may not play by the rulebook. It may decide that anything from Uganda, even if it passes through DRC, Kenya, or Tanzania, will not be eligible for export to the US market so long as it is originally from Uganda, will not be accepted. So, even those companies that may want to relocate, their products must be from Kenya, made in Tanzania or Rwanda, but not from Uganda,” Mr Ndirangu said.

According to the US Department of State, the US provides significant health and development assistance to Uganda, with a total assistance budget exceeding $950 million per year.

Mr Ndirangu says if the ingredients in the pharmaceutical industry come from the rest of Africa, then Uganda could scale up its pharmaceuticals under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

“You recall that Uganda was once ahead of Kenya in the production of ARVs. There are two ways: Uganda could still trade with the US but their products will attract normal rates/taxes,” said Mr Ndirangu. “If the US wants the Ugandan ARVs, for instance, they can still buy directly from Uganda, but not under the Agoa. This could give Uganda a chance to produce for Africa under the AfCFTA. Our biggest problem is thinking that we can only survive under one market.”

A stronger Kampala?

The country’s export portfolio extended to encompass footwear, minerals and metals, all benefiting from Aoga preferential treatment, but all that may go up in smoke, with the country’s Trade minister Francis Mwebesa saying Uganda will emerge stronger.

“We shall remain strong. There is no doubt about it. Uganda is not going to have any problem as we have standards in Uganda,” said Mr Mwebesa, who hinted that Uganda could turn to the recently signed Kenya-EAC-European Union Economic Partnership Agreement.

Uganda was one of the countries that was eligible under Agoa, though, due to low capacity, this opportunity had not been fully utilised. Countries with lower utilisation rates such as Uganda typically had few exports to the US in general, as their primary traded goods, a finding the private sector in Uganda agreed with.

“The very first impact (of Agoa) is directly hitting the business ventures of a number of producers who have been taking advantage of the Agoa provisions and had established a clear and consistent line of trade into the US under the Agoatariff lines,” said Simon Kaheru, vice-chair of East African Business Council, Uganda chapter.

The private sector also termed the US move political, as Agoa has failed to lift Uganda out of poverty.

“On the whole — from a macro level — the numbers do not appear impressive, which made the move appear to be even more political than the reasons for it,” said Mr Kaheru.

Industry players note that a dearth of critical infrastructure in logistics and machinery, deficient export-processing zones, and a lacklustre supervision in various production chains hindered Uganda’s ability to meet the exerting US market standards.

“My personal understanding is that this did not help the dialogue between the two governments, because Uganda can plug that trade hole by simply doing a few things differently. Compare the values of imported second-hand clothing with those of goods exported under Agoa and consider where we could do better overall by approaching the matter very differently,” said Mr Kaheru.

The government had identified garments as the main export to utilise this treaty, but the project hit a dead end due to allegations of mismanagement.

The US International Trade Commission last year released its report that showed that the impact of the Agoa programme on beneficiary countries can be substantial depending on the sector, especially apparel. But Uganda’s Agoa aspirations were challenged by a range of obstacles, and the latest decision reverses the few gains the country had made.