Prime

Why cost of your data bundles has increased

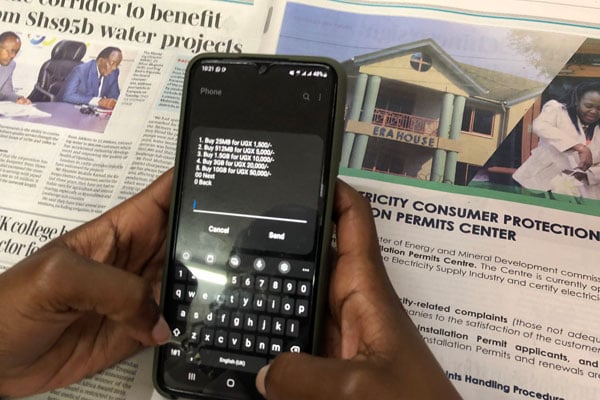

A woman buys data. Uganda reportedly has the highest cost of Internet use in the world. Photo/Sharon Katusiime

What you need to know:

- The communications industry, particularly the telecommunications industry, has major exogenous expenses such as the electricity factor as well as significant capital and operations costs.

- Experts say the cost of using the Internet will drop as more people use it.

- Due to service volatility brought on by Kenya’s topography, it is not commercially advisable to rely solely on routes through that country.

Uganda has the highest cost of Internet use in the world and is only rivalled by the Ivory Coast, according to the 2022 report by Surfshark, a cybersecurity firm in the Netherlands that offers virtual private network (VPN) services, data leak detection systems, and private search tools released last month.

Days after the Surfshark study was released, telecoms in Uganda again made variations to their data bundles. Several data packages were raised.

Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) Executive Director Irene Kaggwa Ssewankambo in an interview confirmed that the changes are not restricted to one telecom, but were initiated by all the providers.

“As consumers, we desire to pay the cheapest we can and thus usually enjoy price wars among providers, but this can have adverse impact in the medium to long run due to providers ending up operating below marginal cost and being forced to compromise on quality to deliver the price desired by consumers and collapse of some companies,” she told this publication.

For example, Ms Ssewankambo explains that this is already straining the fixed Internet connectivity market in Uganda.

How does Uganda compare to others?

According to Surfshark’s most recent data from 2022, Uganda’s Internet affordability ranks 116th out of 117 nations surveyed internationally, comprising 92 percent of the world’s population.

This suggests that, by worldwide standards, Internet connectivity in Uganda is pricey. Ugandans, therefore, must work an average of two weeks to afford the cheapest fixed broadband Internet bundle.

The five main pillars of digital wellness used in the study to assess each country were Internet quality, affordability, e-security (such as information security), e-government (public services offered online), and e-infrastructure (the combination of digital technologies, resources, communications and the people needed to manage them).

Consumer spending patterns, Ms Ssewankambo says, have changed this year across the entire economy as a result of the rise in the cost of living and skyrocketing commodity prices. This has impacted the arithmetic in adjusting the bundle offers on the market.

UCC is mandated to regulate rates and charges for communication services, with a view of protecting consumers from excessive tariffs and to prevent unfair competitive practices. In reviewing tariffs, UCC considers how a proposed tariff is relative to the cost of producing that service. This takes into consideration any sector wide or macroeconomic events.

What has triggered the recent data price increments?

The recent increase, according to UCC, is largely driven by the jump in diesel prices. Whereas it is wished that all the networks in Uganda be powered by electricity, in some locations, the national grid is not available. In other locations, availability of grip power—which averages between 80 to 85 percent—necessitates the use of alternative power. Currently, this is largely a diesel generator.

“As UCC, we are engaged in identifying and making interventions with other stakeholders in government and private sector to improve affordability of communications services in Uganda,” Ms Ssewankambo said, adding: “This, in our considered opinion, is critical to the realisation of our vision of an inclusive digital economy.”

The communications industry, particularly the telecommunications industry, has major exogenous expenses such as the electricity factor as well as significant capital and operations costs.

To lower the cost per unit for each customer, the majority of these expenses are often shared among the subscriber base. This is true because some places do not generate enough cash to cover the expense of providing the service.

UCC says it, therefore, has to guarantee that tariffs are not being implemented at the cost of consumers in order to quickly repay investment.

“We remain positive that we shall soon resume the trajectory of decline in tariffs charged for communications services in Uganda to facilitate more persons across the country to enjoy and benefit from ICTs,” she says.

What about the issue of expired data?

Given that users must pay more money to purchase new data bundles when their current subscriptions expire without using up the package they paid for, the expiry of data bundles is intimately tied to the cost of data.

When the telecoms go to buy the data, they negotiate deals that determine the nature of the bundles that will be sold. In most cases, the expired data bundles are sold cheaper than the ones without an expiration date, according to Abdu Waiswa, head of legal and compliance at UCC.

In August, Mr Waiswa told Parliament that data bundles expire because the Internet is a product that is imported by the service provider in Uganda.

He clarified that in most circumstances, the agreement that will let this bundle expire is supplied at better conditions than the one that is open.

Additionally, because these operators also purchase such bundles, they structure them so that they may advertise them to customers who can choose to purchase an open or expired bundle.

Why was the tax regime tweaked?

The tax regime is also a big factor. After getting rid of the Over-The-Top (OTT) tax, the government imposed another tax of 12 percent on the net cost of Internet data, after which an additional 18 percent value added tax (VAT) will be charged.

The controversial OTT tax, sometimes referred to as the “social media tax” was implemented on July 1, 2018. It costs Ugandans Shs200 per day to use more than 50 platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. The social media tax would discourage Internet use and fall short of its revenue goals.

When the government submitted its plans to enact the OTT tax, the Finance ministry estimated that by 2022 it might bring in up to Shs486b annually. This reduced to Shs284b yearly by the end of July 2018. And in July 2019, the taxman revealed that only Shs49.5b had been collected, an annual shortfall of 83 percent.

What’s the impact of a small user base?

The operational costs are the same even while just a small portion of telecoms’ facilities, including Internet cables, are used. The cost of using the Internet will drop dramatically as more people use it.

Tanzania has an Internet penetration rate of 38 percent, Kenya 53 percent, and Uganda 29.4 percent. Only 20 percent of people in Uganda have smartphones.

Some of the recommendations include giving telecoms more spectrum to support a new technology that would easily translate into price reductions and significantly lower operational costs. Also, lowering import duties on smartphones to lower overall prices for potential customers would prove handy.

Why are Internet costs prohibitively high?

In Uganda, one gigabyte of Internet access costs around $2.67 (Shs10,111). The cost of the Internet is dependent on numerous factors, most notably the expense of backhauling across Kenya and Tanzania and of bringing services into the nation from fibre links at the coastlines.

Fibre cables are used to transfer Internet traffic along a 920-kilometre line that passes through Kenya. The cost of backhaul routes through Tanzania from their port to the border is high.

Due to service volatility brought on by Kenya’s topography, it is not commercially advisable to rely solely on routes through that country. These are not expenses that the other East African nations face. Data prices should decrease as a result of the national broadband policy’s implementation, which was approved in 2018.

The strategy, which encourages infrastructure sharing and forbids duplication of investments, is intended to cut operators’ investment costs, which will lower the cost of the Internet (service delivery) and lower data rates.

Although fibre cables are now less expensive than the satellites Uganda utilised 10 years ago, technological innovations like Google’s balloons are anticipated to revolutionise data transmission.