Book offers views third World feminism

What you need to know:

- It also challenges white feminists, whose “sisterhood” it brings into question as its race-related subjectivities added color of meaning, if you please, to third wave feminism. Its Ugandan equivalent takes a slightly different tack.

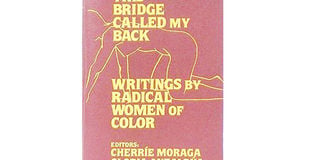

“This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color” is a feminist anthology.

Employing what is known as Intersectionality, which is “an analytical framework for understanding how individuals’ various social and political identities result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege,” it centers on the experiences of women of colour.

It also challenges white feminists, whose “sisterhood” it brings into question as its race-related subjectivities added color of meaning, if you please, to third wave feminism. Its Ugandan equivalent takes a slightly different tack.

“This Bridge Called Woman” brings together women across culture, color, time and geographical distance to produce non-fiction essays.

Here, several Ugandan women interviewed several American (largely Californian) women, and vice versa, each producing a narrative work reflecting their conversations.

Out of these conversations, writings, paintings and pictures of 62 direct female participants came into being.

To be sure, 21 storytellers (11 from Uganda and 10 from the U.S.), 20 women visual artists and photographers, 20 women writers and two editors undertook this cross-cultural venture in cross-storytelling and cross-writing to foreground international feminist experiences of an integrationist, intersectionality bent.

This was achieved by the well-told stories of the women involved in this rather unique cross-cultural anthology of women biographies from Uganda and USA.

In collaboration with Women’s Wisdom Art, USA, and with support from the US Embassy Uganda, Uganda Women Writers’ Association (FEMRITE) has set a high bar with this literary offering.

The book begins with Dr. Olivia Kasirye, a public health and general preventive medicine specialist in Sacramento, California, USA. Her vast experience in cultivating the medical field towards the golden harvest of glowing accomplishment earned her the Mort Friedman Civic Leadership Award.

“This award honours outstanding individuals who demonstrate a passionate commitment to public service through their work and community leadership,” Beatrice Lamwaka writes when narrating Dr. Kasirye’s story.

In 2021, Lamwaka tells us, “Dr K” and her team were officially recognised by the Mayor of Sacramento, Darrell Steinberg, during his State of the City address, for “steadfastly [leading] Sacramento County’s response to Covid-19 in the most difficult time, ever, she never flinched during the toughest time of the pandemic.”

However, it is not the brass rings illumining the good doctor’s trophy cabinet that set her apart; it is her humanity.

Rarely, especially in this cynical age, do you get a doctor whose bedside manner is akin to the legendary Florence Nightingale’s humanism.

Diana Tumminia then tells us about Jane Frances Kuka going eyeball to eyeball with female genital mutilation (FGM), ensuring the latter blinked when the practice was outlawed in 2010.

This extraordinary woman, awarded with the Distinguished Class IV Medal of the Nile, showed up the patriarchy’s feet of clay by molding an activism out of the dreams her mother had for to become a leader who made a difference.

April Jean, as told to us by Davina Philomena Kawuma, is a “racial justice trainer, consultant, community organizer and systems change strategist whose 18-year career has focused on illuminating the impacts of race and racism on systems, institutions, organizations, communities, and individuals who identify as Black/African American.”

She is not only an accomplished lady, she is patently inspirational.

Eulonda Kay Lea then tells us about Dominica Angela, better known as Sr. Dominic Dipio. She is a Ph.D. professor, Fulbright scholar, first African female to serve as the head of the Department of Literature at Makerere University. She is blessed with the salvation of the biblical Samaritan Woman.

Although there are plenty, a plethora actually, of stories about outstanding women in this book, Rachel Rios, born to a Mexican mother and a Mexican American father, stands out in this company of standouts.

Her story is rendered by Glaydah Namukasa and carries invaluable lessons for all those who wish to make a meaningful contribution to society.

Still, it was Rios’s mother who reminded her that “every person’s situation is different. It’s their life and we must honor that…how do we advocate for others in a way that doesn’t put their lives or livelihood in danger?”

In a world where activists shoot first and then take aim afterwards when attempting to overcome racial, cultural or gender barriers, Rios’s example reminds us that we must respect contexts in order to insinuate change within their circumscriptions.

Margaret Erin Saberi then tells us about Professor Joy Constance Kwesiga, a Ugandan academic, academic administrator, gender specialist, community activist, one of the founders of Action for Development (ACFODE) and vice chancellor of Kabale University.

She is the “Lucky Rural Girl” who beat the odds by championing women’s rights in a patriarchal world reminding us that the world will not be changed by our arguments. It will be changed by our example.