Prime

Book Review: Muhindo gives us literature by other means in new book

What you need to know:

- By combining yet separating the elements of prose and poetry, Muhindo has given us literature by other means. And by these means, he has injected morality tales, and, yes, love into a sweeping narrative.

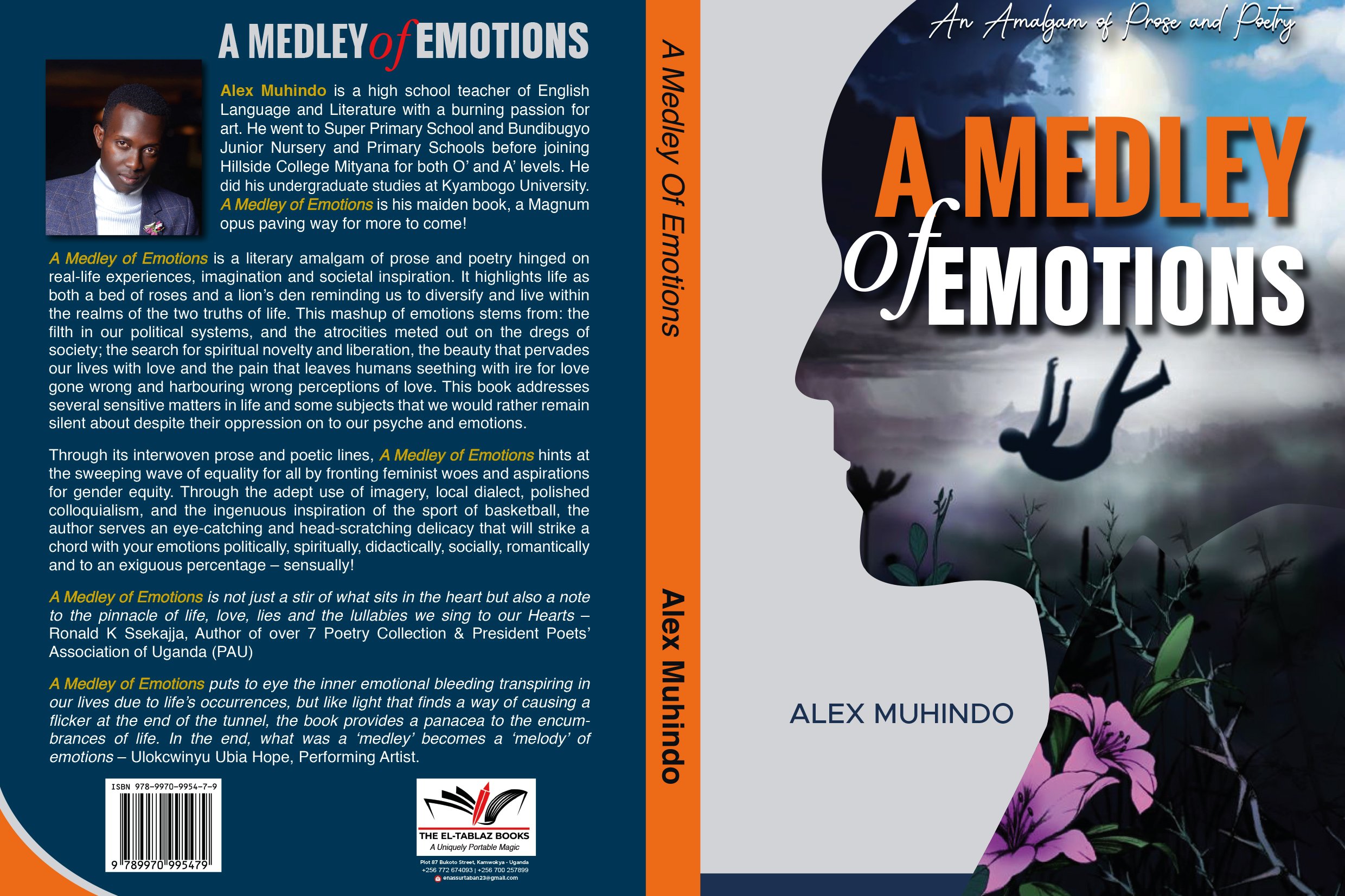

Author

Alex Muhindo

Price

Shs35,000

Where:

Uganda Museum Library

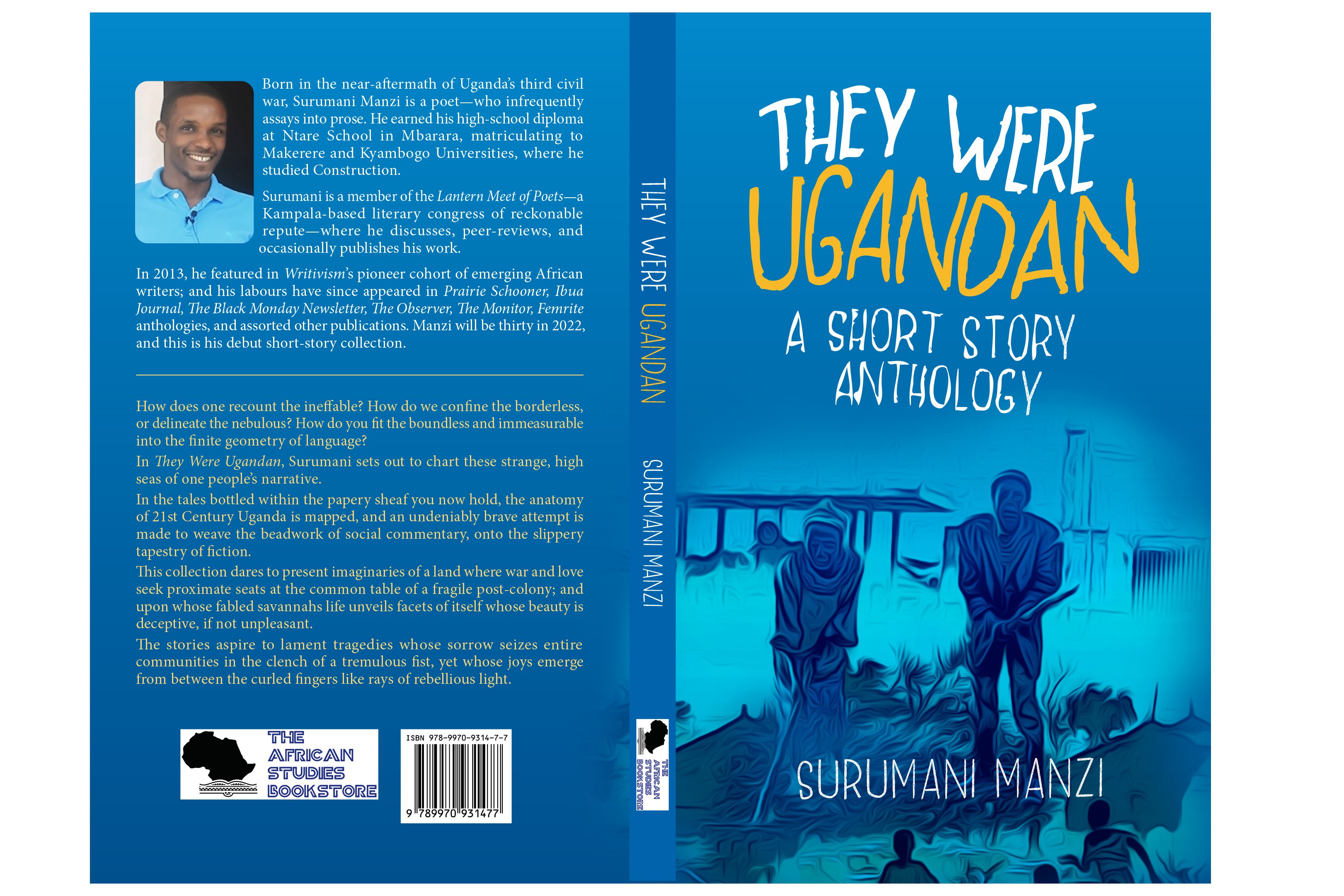

Alex Muhindo’s freshman book, A Medley of Emotions, is—in his own words—an amalgam of prose and poetry. This integrated approach is projected by short stories-cum-essays-cum-poetry as a multihyphenate of literature. There is even one speech gratuitously thrown into the bargain, no less.

A Medley of Emotions inaugurates this mixed-bag offering with “My Beautiful neighbour”, a short story told in the first-person narrative. This sort of narrative is a form of storytelling in which a storyteller recounts events using first-person grammar such as “I”, “me”, “my”, and “myself”.

It is essentially from the storyteller’s own point of view, even though sometimes fictionalised. Here, the narrative introduces Dave, who falls for a spirited young lady called Edythe. With the help of his 10-year-old sister Belinda, who serves as a conduit bringing the two together, Dave gets to meet his love-interest. Edythe then returns the complement of Dave’s interest in her by falling for him. The star-crossed lovers are inseparable until Dave, the resident stud, decides that his ex-girlfriend, Shanita, should triangulate the love they share. All the while, Dave’s erstwhile best buddy, Gareth, takes the proverbial hindmost, alongside the devil, by attempting to drive a wedge between Dave and Edythe.

This fable then takes a sharp turn, as this budding love story descends into a vortex of treachery, jealousy, revenge and sheer malice. In “Two Wrongs Make a Right”, the second and last short story, we are introduced to lady-killer Jerry. He is eternally footloose and fancy-free, until he sets eyes on the church girl Suzanne. The two get married. But before they can walk into the sunset, their love is sorely tested by betrayal. “You saved me, darling,” Jerry eventually tells Suzanne who answers, “How?”

“Cheating on me healed my blindness,” Jerry rejoins. However, God is in the details and so it would be ungodly of me to spoil the story by telling you how the two made things right, by making them wrong.

In the second section of this book, essays instructive of love “Fall For Your Type” as well as gratitude “Ingratitude” sit easily with an essay on the libidinal possibilities of Afghan refugees, who were in Uganda, coupling with Ugandan men, and women.

Muhindo, however, is at his best when relating his childhood escapades in essay form. “My real story ignited in the second week of Senior One when John’s girlfriend, Hilda playfully came sat on my thighs and suddenly kissed me, an act I later realised had been intended to avenge her for John’s endless philandering,” he discloses, adding, “Unfortunately, Hilda did this in keen observance of some bimbo who used it as an opportunity to humiliate me during the later orientation day.”

In the last section of this book, Poetry, Muhindo starts off politically with the poem entitled, “Reproof from Mr Above.” Mr Above is glowering when he declares: “Listen! Like the Baptist, I’ll behead you if you think the truth still sets you, dregs of society, free!” Like a typical tinhorn dictator, Mr Above huffs and puffs threatening to blow our world back to the Dark Ages.

One of the best poems here is The Coquette. “In men’s hearts she breaks without any brakes,” is a clever rhyme showing a flirtatious woman who is more into the kill of the chase than the thrill of the chaste, if you will. Muhindo’s poems are modular: they serve you bite-sized doses of this and that, representing the uniformity of a larger literary whole. His prose, too, comes at you in such a variety of forms that you may mix and match each word and inflection to enjoy what works for you. The interior oratory of his words rhetorically seizes each emotion to match it with a thought.

As a result, his writings are often quite beautiful, especially when dressed in the everyday clothes of colloquial expression.

By combining yet separating the elements of prose and poetry, Muhindo has given us literature by other means. And by these means, he has injected morality tales, and, yes, love into a sweeping narrative.