Prime

Book review: Mujuni’s collection of poems displays power

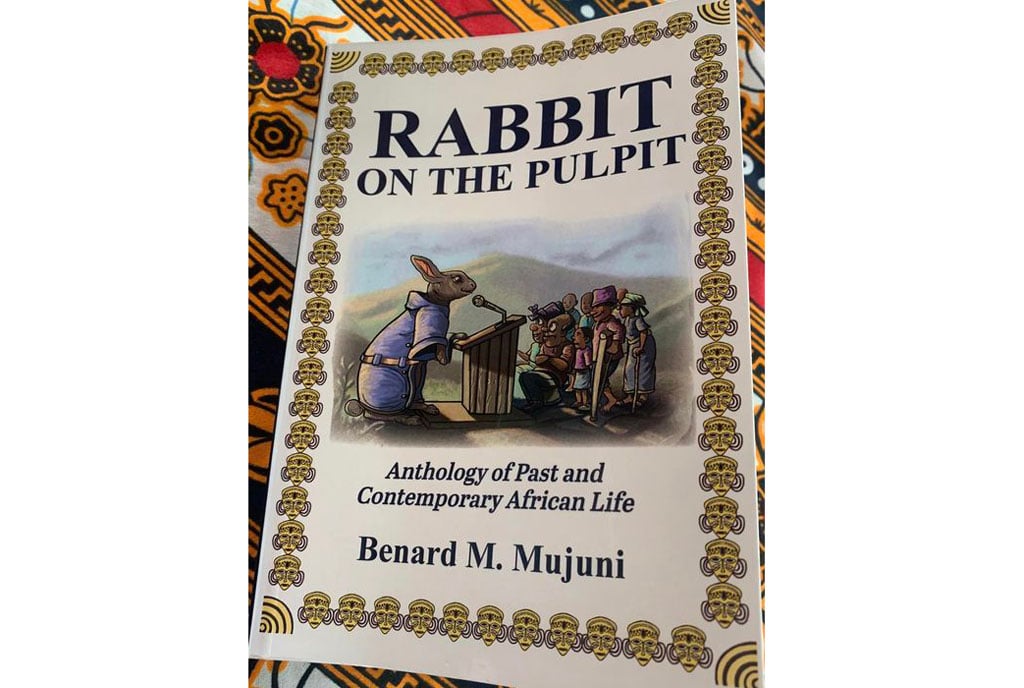

Book cover.

What you need to know:

- Book title: Rabbit on the Pulpit

- Author: Bernard Mujuni

- Pages: 194

- Price: Shs40,000

- Where: Aristoc Booklex.

Uganda’s former head of state Milton Apollo Obote loved poetry, his favourite poem being John Milton’s “A Paradise Lost.”

This poem was an epic. An epic poem is defined as a lengthy, narrative work of poetry. You know, like the one about the battle of Troy, which set out in detailed verse extraordinary feats and adventures of characters from a distant past.

This is precisely what Bernard Mujuni’s collection of poems, intriguingly titled “Rabbit on the Pulpit”, is about. Mujuni’s poems are of the genre of “Pastoral Poetry”, which depicts the glories of rural living and is thereby set in the countryside (reflecting the rustic landscape of western Uganda where the poet grew up).

“My elder brother gave me a ride/On a tough bicycle-fiasco/That took us a day/To scale and stretch/Through the way/Eh! My butt hurt!/It was a tough and rough ride/We pitched camp In Mushanga/Where my uncle, Ishanga/Had planned for his son Mushanga to enrol,” writes Mujuni in the opening poem: OF DEMI god LIGHTS IN KYANGYENYI. I think you get the drift?

Mujuni, a humourist, employs funny scenarios, fables, vignettes and the like, which involve dialogues between simple rural folk in ways that keep the reader glued to each page.

He continuously and consistently draws upon authentic folk traditions with a blend of simplicity and sophistication that introduces Pastoral verse to us, the readers, in friendly somewhat naughty doses.

“Every Thursday was market day/Kafiti the village wag/Lived in Bwizi, where dogs were known/For overly wagging their tails/Bwizi, the land of whizzing trees/With several tales/Must I say more? The boys in the farms stood so firm/Waiting for the birds to confirm/The arrival from the fairly market tales/Chuckling chicky-chicky like chimes/Making waiting boys almost explode/At a mere exposure of breasts/Must I say more?” he writes in the poem; KAFITI AND THE THORNY TREE.

You can bet that, later, he rhymes “thorny” with a similar word that drops the “t” in the word “Thorny” in order to describe, in extravagant language, how the village boys felt when they finally saw female breasts.

Mujuni playfully contrasts between urban and rural lifestyles as he presents an idealised portrayal of the lives of rural Ugandan folk while still employing the traditional and not-so-idealised pastoral conventions of the everyday existence of villagers.

“There was once a village/In Mbarara where people danced/With lots of rage and at a pace/Holding their waists/So tight as waistlines/Shook like people from the West/While about seven, I met a tall weird man/Who looked like Museveni/It was around seven in the evening/With a hat placed on his head, his beard clean shaven/My cousin had wooed me to a village dance/To which I followed like a misled sheep/Jumping at this irresistible chance/To dance with the mischievous village queen,” he continues in the poem THE FUNDUKURU DANCE.

The billion shilling question on your mind is, I bet, does he get the Mischievous Village Queen?

Well, you have to get the book and find out whether the “dance” remains on the proverbial streets or migrates to between the bed sheets.

Regardless of what happens, though, the subtext of every poem in this anthology is like an invitation to all of us to get out of the city and explore the simple life through pastoral poetry.

It’s the poetry of the countryside, of rolling hills and herdsmen, of the good old days when everything was bad.

Mujuni understands this genre of poetry well since, one might say, he is essentially a villager at heart. I don’t mean this as a criticism, for traditional village life was something of a utopia.

All told, Rabbit on the Pulpit is a literary buffet surfeit of two essential poetic ingredients: pace and rhythm.

It brings together the two poetic vitals with forward looking poetry seen through the lens of a backward glance as it tackles traditional and modern themes in one resounding body of work.

The poems are put together in order to relate to each other as a chronology and testimony of Bernard Mujuni’s life and thought processes. From the tale of Kafiti to the author’s tales of America, the poems stride forth as they gather into singular forces which collectively act as components of a unified whole.

In this vein, they serve one another as movers and breathers to achieve a measured tempo. Much of the verse in this anthology is sustained by varying twists to the viewpoint and experiences of its author. Thereby making the book confessional and autobiographical, as well as philosophical, as the central thrusts around which this selection of poems resides in tune with Mujuni’s worldview.

As he documents his thoughts, feelings and life, the idea of poetry’s therapeutic power is at the heart of his work. Each syllable never misses a beat, touring the country of his inner self with near-geographic abandon.

This anthology is themed around the aspirations and inspirations that draw people to poetry at life’s turning points—family, love, breakup, loss, tradition and certain rites of passage which separate now from then as they bring past and present into a single narrative.

His work is indeed historic and contemporary, the latter being well articulated by some of his experiences during the Covid-19 lockdown. These experiences will shape the foundations of his next anthology but can also be felt in the rhythm and rhymes of this magnum opus.

Three years ago, when Mujuni embarked on this anthology, it was at a very different place in the recesses of his mind. Then, when his words sprang onto paper, he condensed this secondary version of his anthology (that first existed in his fertile mind) with the contours of emotions and ideas which took shape in different stanzas. In so doing, he has written a fine book.